Ijraset Journal For Research in Applied Science and Engineering Technology

- Home / Ijraset

- On This Page

- Abstract

- Introduction

- Conclusion

- References

- Copyright

Analyzing Recent Indian Agricultural Reforms: Implications for the Sector and Economy

Authors: Bhavya Jain, Dhruv Jain, Divyansh Bhansali

DOI Link: https://doi.org/10.22214/ijraset.2023.56251

Certificate: View Certificate

Abstract

With a focus on two main areas, this article examines the recent agricultural reforms in India and their effects on the industry and economy. Specifically, it looks at the three farm laws in depth, weighing their advantages and disadvantages, and draws comparisons with the economic changes of 1991. These regulations are set against the backdrop of India\'s changing economic landscape, which has been characterized by class disputes in agriculture and inequities between urban and rural areas since the 1990s. The objectives of the Farmer\'s Produce Trade and Commerce Act, 2020 are to decrease middlemen and increase market access. Potential effects on the Minimum Support Price (MSP) system are the main source of concern. Modernizing farming processes, lowering risks, and promoting comprehensive crop production agreements are the goals of the Farmers (Empowerment and Protection) Agreement on Price Assurance and Farm Service Act, 2020. Among the difficulties are a lack of literacy among farmers and differences in the contractual parties\' capacities. The Essential Commodities Act, 2020 modifies the essential goods regulation system with the goal of minimizing government involvement while guaranteeing a steady supply of essentials. Its dynamic nature and potential for consumer abuse give rise to concerns. Regarding rice marketing, these regulations could affect individual rice varieties, increase farmers\' market access and autonomy, remove storage ceilings, and mostly help rice growers. To fully comprehend the complex effects of these farm regulations on India\'s agriculture and economy, more study and analysis are necessary.

Introduction

I. INTRODUCTION

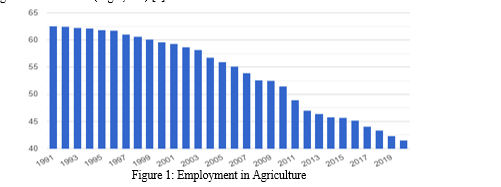

India has always been an agrarian nation, making it more rural and labor-intensive. It employed around 70% of the population in the 1970s, but since then, the percentage has been declining; in 2011, it employed roughly 48.6%. The employment in the agriculture over the period of time has been represented in the Figure 1. It remains an agrarian nation notwithstanding the decline in the proportion of workers involved in agriculture. But despite the fact that about half of the working population is either directly or indirectly employed in agriculture, the sector only contributes about 17% of the GDP. Agriculture continues to be one of the most significant economic sectors despite the disparity in income between the number of employed and employed persons. This is because agriculture is one of the main exports from the country and supports other industries such as the textile sector (cotton, fabrics, etc.) and sugarcane derivatives (sugar, etc.) [1].

In September 2020, the Indian government passed three Acts totaling a number of agricultural laws. Despite repeated requests from opposition parties to refer the bills to a select parliamentary committee, the laws were enacted in parliament with little discussion [2]. Farmer protests started as soon as the Acts were passed. Trade unions and opposition parties have stated that they back farmers who are opposed to the three Acts [2].

A few state legislatures have passed measures to overturn the new rules, including those of Punjab, Rajasthan, and Chhattisgarh. The government has lost a Union Minister (Minister of Food Processing Industries) who quit over these rules, calling them "anti-farmer ordinances and legislation." The legislation have been placed on hold until further orders by the Indian Supreme Court. Nonetheless, the government continues to argue that these rules are advantageous to farmers and the agriculture industry. The most recent farm legislation in India are contextualized in this essay within the broader political economy of neoliberal reforms that started in 1991. It contends that class is a major factor in India's agrarian discontent and that the present farmer protests must grow into a larger movement centered on social justice [3].

This paper's primary goal is to investigate how the nation's agriculture sector is affected by the recently passed farm laws and how this affects the GDP and the overall economy. More precisely, there are two main aspects to the paper's objectives. In the first place, it attempts to conduct a thorough examination of the three farm laws, analyzing their benefits and drawbacks and drawing comparisons with the 1991 economic reform that brought about a great deal of change to India's economic environment. Second, the study will look specifically at how these farm regulations affect rice marketing, which is an important aspect of the agricultural industry and has a big impact on the economy of the country. By offering insightful information about the complex ramifications of these laws, this study hopes to add significantly to the current discussion about how these laws affect the agriculture industry and the economy as a whole.

II. THE POLITICAL ECONOMY OF INDIA'S REFORMS

India saw significant economic reforms in the 1990s, including the removal of trade restrictions, the opening up of previously state-owned industries to private investment, such as information technology, defense, and pharmaceuticals, the devaluation of the rupee, fiscal correction, and financial sector reforms. Although the Indian economy expanded at a rate of roughly 6% annually starting in the mid-1990s [4] several observers have questioned the country's performance in terms of various development indicators, including child malnutrition, employment, income inequality, and poverty [5]. One way to describe the post-reform era is as one of uneven development, with urban areas reaping benefits at the price of rural areas, which nevertheless house the majority of India's people.

In the 1990s, trade restrictions were lifted, state-owned industries like information technology, defense, and pharmaceuticals were opened to private investment, the rupee was devalued, fiscal correction took place, and financial sector reforms were implemented in India. Since the mid-1990s, the Indian economy has grown at an approximate annual rate of 6% [6]. However, a number of analysts have expressed concerns about the nation's performance with regard to a number of development indicators, such as employment, income inequality, child malnutrition, and poverty [7]. The post-reform era might be characterized as unevenly developed, with metropolitan areas benefiting at the expense of rural areas, which yet are home to the vast majority of India's population.

Conflict between agrarian classes has characterized the nation's agricultural status overall. Class disputes arose between the landless peasants and the higher classes, or landed gentry, after the feudal (Zamindari) system was abolished in the 1950s [8]. Similarly, the higher classes, who had historically owned large tracts of land, benefited most from the Green Revolution of the 1970s, which rendered India self-sufficient in the production of food grains [9]. The gap between the affluent rural elites and the impoverished peasantry—which comprises agricultural laborers, landless peasants, and small- and medium-sized landowners—was widened even further by the neoliberal reforms of the 1990s. As a result, it is possible to view the current set of farm regulations as an extension of the marketing and distribution reforms made in the agricultural industry.

Within Indian policy circles, the concept of deregulated agricultural markets has been discussed since the early 2000s. The BJP-led NDA government established the Guru Committee on Marketing Infrastructure & Agricultural Marketing Reforms, which released its 74-page report in 2001 (Ministry of Agriculture Citation 2001). Here are a few of the report's suggestions that are noteworthy. According to the report, "the Government needs to examine all existing policies, rules, and regulations with a view to remove all legal provisions inhibiting a free marketing system in order to promote vibrant competitive marketing systems" (Ministry of Agriculture Citation 2001, 4).

The Essential Commodities Act, 1955, which led to restrictions on stock storage and free movement and was prompted by trade in innovation and investment, should be repealed to allow free market forces to function as they should, the report continued, making specific recommendations.As one of the alternative marketing structures that maintains incentives for quality and increased productivity, lowers distribution losses, and raises farmer incomes through better technical assistance and processes, the Committee recommends promoting direct marketing.

The market will be run by private industry professionals, wholesalers, trade associations, and other investors, and it will not be governed by the Agricultural Produce Marketing Act.

III. THREE FARM LAWS

A.The Farmer’s Produce Trade and Commerce (Promotion and Facilitation) Act, 2020

One important piece of legislation, the Farmer's Produce Trade and Commerce (Promotion and Facilitation) Act, was introduced primarily to give Indian farmers access to a wider market by enabling them to sell their agricultural produce outside of the conventional State Agricultural Produce Marketing Committee (APMC) Mandis. The landscape of agricultural policy has changed strategically, and this has brought forth a number of important benefits. First and foremost, it gives farmers the priceless freedom to investigate markets all over India, giving them the chance to get the best prices for their produce and helping to expand platforms such as the Government of India's eNAM, an online marketplace for agricultural commodities that speeds up price discovery [10].

One very notable result of the Act is the removal of intermediaries, which essentially creates a direct connection between the manufacturer and the consumer. This in turn is expected to reduce consumer purchasing expenses while also removing the exorbitant costs linked to middlemen, hence increasing farmers' revenue. Beyond these advantages, the law also helps to reduce time delays and corruption, two things that have historically hindered interstate agricultural trading. The Act expands the range of opportunities accessible to farmers and gives them more market flexibility by allowing them to continue using the current APMC institutions [11].

Because the ultimate cost of items is lower due to the lower cost of agricultural commodities resulting from these changes, consumer welfare is improved. This is especially important in a nation where a major portion of the population is dependent on agriculture. Notably, the Act relieves farmers of charges and market fees while also relieving them of the need for paying transportation expenses, which has been viewed as a major benefit for individuals involved in farming. Though theoretically promising, the Act has real difficulties in the context of Indian agriculture [12]. The vast majority of Indian farmers are classified as small and marginalized farmers, and they frequently struggle to make ends meet on their land holdings, let alone produce enough excess for the market.

In addition, the public is quite concerned about the possible outcomes of this legislative reform. Many people are afraid that APMC Mandis, which have long been essential to the agricultural trade environment, would eventually be phased out as a result of a coordinated campaign by the trading community. These concerns imply that the well-established Minimum Support Price (MSP) system, which has historically protected farmers' interests, may be in jeopardy once this shift occurs. In a situation like this, the trading community might control and sell all agricultural produce, which would raise questions about the long-term viability and profitability of farming.

B. The Farmers (Empowerment and Protection) Agreement on Price Assurance and Farm Service Act, 2020

The Farmers (Empowerment and Protection) Agreement on Price Assurance and Farm Service Act, which aims to give legal validity to contractual agreements between farmers and sponsors, is a turning point in the history of agricultural policy in India. Fundamentally, the goal of this law is to bring farming practices up to date by promoting pre-planting agreements that precisely specify crop production parameters and costs. This proactive strategy offers several benefits. First of all, it includes extensive contracts that guarantee farmers' financial stability while also frequently entail sponsors assuming a mentorship role, offering professional advice, high-quality seeds, and additional inputs like pesticides, in addition to support in the form of advance credit, training, and the purchase of essential farming equipment [13].

Furthermore, the Act reduces the risks that come with agriculture by providing "Force Majeure" clauses that provide insurance coverage against unanticipated market shifts and natural disasters. This creates a win-win situation where sponsors get the premium agricultural produce they need and farmers have stable incomes. In order to protect farmers' rights and promote third-party grade certification for increased openness, the government plays a crucial role in this legislation. Furthermore, there is a strong dispute resolution process in place that includes restrictions against the sale of farmers' land for uses other than agriculture as well as provisions for prompt appeals.

Despite these encouraging possibilities, there are still issues that need to be resolved. These include the low literacy rates among farmers, the risks they incur, the differences in competence and capability between contractual parties, and the difficulty in accessing resources related to justice.

These difficulties highlight the necessity for a comprehensive strategy to successfully implement the Act and guarantee that the intended changes to India's agricultural environment are fair and inclusive for all parties concerned [14]. With the primary goals of guaranteeing farmers' income security and promoting a more stable and prosperous agricultural sector, this legislation essentially represents a fundamental shift in India's agricultural paradigm. It also emphasizes the significance of addressing these challenges holistically.

C. The Essential Commodities (Amendment) Act 2020

The Essential goods Act of 1955 has undergone a recent change that will take effect on June 5, 2020, significantly altering India's regulatory framework for the supply of essential goods. Essentially, the goal of this amendment is to minimize direct government intervention in market dynamics while also guaranteeing the continuous provision of necessities like food and medicine. In an effort to update the current laws, it adds a number of interesting provisions. Positively, the amendment caps storage limits to discourage hoarding and stockpiling during price spikes, hence reducing the likelihood of artificial inflation brought on by excess reserves.

In addition, the amendment's support of sponsor-farmer contracts aims to simplify agriculture industry business processes and protect farmers' rights while enabling fair market participation. However, detractors contend that rather than taking proactive preventive action, the law is still fundamentally reactive, dealing with issues after they have already arisen. This reactive approach draws criticism since it raises unaddressed concerns regarding the rationale for allowing unrestricted stock storage, which may lead to fake shortages in the market and consumer abuse [15].

Furthermore, worries about potential consumer exploitation have been raised by the Act's threshold for government intervention, which requires prices to dramatically exceed the average before action is taken. Even though the amendment marks a significant change in India's regulatory approach to basic goods, there are still ongoing discussions and debates about it, which illustrates how difficult it is to strike a balance between the interests of different parties involved in the agricultural sector and the overall economy. The final impact of the amendment on India's agricultural landscape as well as its ramifications for farmers, businesses, and consumers are significant components of this developing story that require further research and analysis.

D. Similarities with the 1991 Reforms

India weathered its greatest economic disaster in a stunning two-year period. India's economy grew increasingly integrated with the world economy. From 7.3 percent of GDP in 1990 to 14 percent in 2000, India's total exports of goods and services rose. The rise in imports from 9.9% in 1990 to 16.6% in 2000 was not as significant as it was in 1990. In a decade, the percentage of GDP attributable to overall commerce in goods and services rose from 17.2 percent to 30.6 percent. Reforms have boosted efficiency and given customers more choices because to increasing competition in sectors like banking. Additionally, it has led to increased growth and investment in the private sector. From 36% in 1993–1994 to 26.1% in 1999–2000, poverty decreased. The poverty rate has dropped in both rural and urban areas. Reforms enhanced the output of products and services, which led to a decrease in inflation rates or a stable price increase. Competition also helped to keep inflation under check. These liberalization efforts enhanced the growth rate of the economy and enhanced the role of the public sector that already existed. In the same way, these reforms should be seen as revolutionary developments in the field of agriculture.

There has been a lot of uproar about MSP and the belief that it will be phased out in the future. It should be remembered, however, that MSP only covers only 6% of farmers. It is solely declared to ensure market price stability and to acquire crops from PDS. In the early years, until the act becomes regular, a specific step will be required to ensure price stability. In any case, the government will need to purchase food grains for the PDS in the future. It goes without saying that allowing farmers to sell their produce directly will put many of the middlemen in peril. The increase in MSP is shown in the figure 2.

IV. IMPACT OF FARM LAWS OVER RICE MARKETING

A. The Farmer’s Produce Trade and Commerce (Promotion and Facilitation) Act, 2020

When responding to this question, it's critical to go into great depth on the implications for paddy and rice marketing. In the output market, paddy is usually sold between farmers and wholesalers or between farmers and government organizations (such State Trading Corporation or FCI). Additionally, it is traded in the input market between seed companies and farmers (which is then returned to the farmers) [16].

Traders, consumers, and processors to consumers as well as processors to the government food distribution system (PDS) comprise the bulk of the rice marketing industry. Because of this, farmers' interests in commercial dealings at the start of the commodity's whole value chain in both input and output markets are very small. Because of this, The Farmers' Produce Trade and Commerce (Promotion and Facilitation) Act, 2020 contains extensive provisions that aren't tied to any one good or service. From the standpoint of rice marketing, farmers stand to gain from the rule as it expands their market reach and provides them with greater autonomy in terms of selling choices. Decision-making autonomy combined with a variety of trading opportunities in many markets will surely help farmers earn more lucrative returns. Legalizing interstate trade would also benefit farmers who reside on the periphery of state borders and have easier access to markets across state lines than they do to those within.

Under such conditions, it is anticipated that farm produce marketing expenses will be optimized, positively affecting farmers' net profits. The reform spirit, however, may face obstacles from a variety of sources, including logistical difficulties, inflated marketing costs (should a higher price be realized in the distant marketplace), inflated transaction costs (should future payment for the produce arise), and access to market information (price and arrival) from multiple markets in a remote location. India generally grows two types of rice: basmati and non-basmati. In domestic markets, non-basmati grains are the most traded commodity. Certain grain types are preferred in different places and are typically easily found nearby. For instance, eastern India is the producer and consumer of bold rice. In central India, medium-to fine-grain rice is mostly farmed and consumed locally. A similar pattern may be seen in southern and northern India, with different regions favoring different types of grains. Because the new regulations tend to liberalize the domestic market by enabling interstate commerce, the interstate trade in rice grain may increase greatly while the interstate trade in paddy may only expand somewhat.

B.The Farmers (Empowerment and Protection) Agreement on Price Assurance and Farm Service Act, 2020

When it comes to the production of rice grains, contract farming is evident in three different contexts: 1) the input market as seeds; 2) basmati rice; and 3) organically farmed rice. Conversely, non-basmati rice contract farming is quite rare. Additionally, contract farming is common for commodities with high income elasticity and certain qualitative features or values (GIs) that are in a state of market disequilibrium (supply and demand). These features tempt processors or merchants to enter into an agreement with manufacturers so they can profit from the market by meeting the needs of a certain sector of the economy.

India produces more rice than it uses, despite what the general public believes, and its stocks are piled high. Moreover, it has inelastic demand and is easily accessible to customers from all socioeconomic categories because it is a staple meal in the Indian diet. With the exception of the aforementioned conditions of rice contract farming, the new law would therefore have no direct impact on rice grains in India. The introduction of superior rice cultivars, such as high-protein rice, zink rice, rice with a lower glycaemic index, and other geographically indicated rice types like (GI) rice, could potentially help growers by finding their way into contract farming systems [17].

C.The Essential Commodities (Amendment) Act 2020

The storage ceiling is to be eliminated by the essential commodities statute change. Since processors will be able to maintain massive inventories of grains for year-round processing operations, it is anticipated that the amendment will lead to a quicker clearance of APMC yards, farmyards, and other markets. In addition, because of the quick clearing of the market, supply and demand would always be equal. As a result, there is also a significant chance of avoiding price dampening. Not to mention that rice growers are expected to make a profit from even undesignated market locations [18].

Conclusion

In conclusion, the September 2020 agricultural reforms in India have caused a great deal of debate and farmer protests. Even though the country is agrarian and has a sizable labor force engaged in agriculture, the industry only makes up around 17% of the GDP. The 1990s economic shifts in India that resulted in unequal development between urban and rural areas are taken into consideration when analyzing the reforms. This paper\'s main goal is to evaluate how these agricultural regulations affect the agriculture industry and, in turn, the GDP and general state of the national economy. It focuses on two main areas: a thorough evaluation of the three farm laws, taking into account their benefits and drawbacks as well as a comparison with the economic reforms of 1991; and an in-depth investigation of the ways in which these laws affect rice marketing, which is a vital sector of the agricultural industry and the larger economy. A background of class inequities characterizing India\'s 1990s reforms economy serves as a framework for comprehending the current farmer protests. Indian agriculture has a history of class disputes, and these new rules are essentially continuations of earlier distribution and marketing changes. The Farmer\'s Produce Trade and Commerce Act, 2020 seeks to remove middlemen, create a direct line of communication between producers and consumers, and increase market access for Indian farmers. But there are worries, especially about how it might affect the Minimum Support Price (MSP) system, which protects farmers\' interests. Modern agricultural practices, lower farmer risks, and agreements that outline crop production limits and costs are the goals of the Farmers (Empowerment and Protection) Agreement on Price Assurance and Farm Service Act, 2020. Among the difficulties include low literacy rates among farmers and discrepancies in contractual parties\' capacities. The Essential Commodities Act, 2020 modifies the essential goods regulatory structure with the goal of minimizing government interference while maintaining the availability of essentials. Its reactiveness and susceptibility to consumer exploitation are causes for concern. These laws have particular ramifications for rice marketing. Farmers may have more market access and control thanks to the Farmer\'s Produce Trade and Commerce Act, which could result in higher earnings. The Farmers (Empowerment and Protection) Agreement on Price Assurance and Farm Service Act may improve rice varieties\' marketing, and rice growers may profit from the Essential Commodities Act\'s removal of storage ceilings. In conclusion, these agricultural regulations have a complex effect on India\'s economy and agriculture sector, with both possible advantages and disadvantages. The challenges of striking a balance between the interests of many stakeholders in the agricultural sector and the larger economy are frequently brought up in talks and debates, and further study and analysis are necessary to completely comprehend the ramifications.

References

[1] Banerji, A., and J. V. Meenakshi. 2004. “Buyer Collusion and Efficiency of Government Intervention in Wheat Markets in Northern India: An Asymmetric Structural Auctions Analysis.” American Journal of Agricultural Economics 86 (1): 236–253. [2] Corbridge, S., J. Harriss, and C. Jeffrey. 2013. India Today: Economy, Politics & Society. Cambridge: Polity Press. [3] Cotula, L., S. Vermeulen, R. Leonard, and J. Keeley. 2009. Land Grab or Development Opportunity? Agricultural Investment and International Land Deals in Africa. London/Rome: IIED/FAO/IFAD. [4] Das, R. 2015. “Critical Observations on Neo-Liberalism and India’s New Economic Policy.” Journal of Contemporary Asia 45 (4): 715–726. [5] Datla, K. 2020. “Farm Laws 2020: Who are They Meant to Serve?” Down to Earth. Accessed March, 15, 2021. [6] Economic and Political Weekly. 2020. “Bills of Contention.” Economic and Political Weekly 55 (39), Accessed October 16, 2020. [7] Economic Survey of India. 2019–2020. “Ministry of Finance.” The Government of India. Accessed January 17, 2021, [8] Financial Times. 2010. “Hedging Helps Foodmakers Through Uncertainty.” Accessed September 18, 2020. [9] Gadgil, M., and R. Guha. 2005. The Use and Abuse of Nature: Incorporating This Fissured Land, Ecology and Equity. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [10] Golait, S., and R. Lokare. 2008. “Capital Adequacy in Indian Agriculture: A Riposte.” Reserve Bank of India Occasional Papers, 29/1. New Delhi. [11] Haq, Z. 2020. “Here’s Why Farm Protests have been Loudest in Punjab and Haryana.” Hindustan Times. Accessed October 4, 2020. [12] Haynes, M. 2008. “Hunger Amidst Plenty.” Socialist Review 360 (78). Accessed June 3, 2020. [13] The Hindu. 2020. “Protests Against Farm Laws Hit Normal Life in Punjab.” Accessed September 27, 2020. [14] Hussain, S. 2018. “Higher MSP Do Not Truly Benefit Farmers.” The Mint. Accessed October 3, 2020. [15] Jodhka, S. 2012. “Agrarian Changes in the Times of (Neo-Liberal) ‘Crises’ Revisiting Attached Labour in Haryana.” Economic and Political Weekly 47 (26&27): 5–13. Kennedy, L. 2020. “The Politics of Land Acquisition in Haryana: Managing Dominant Caste Interests in the Name of Development.” Journal of Contemporary Asia 50 (5): 743–760. [16] Kumar, R. 2021. “100 Days Later, the Farmers’ Protest is Alive, Well and Gaining Momentum”. The Wire. Accessed April 10, 2021. [17] Lerche, J. 2013. “The Agrarian Question in Neoliberal India: Agrarian Transition Bypassed?” Journal of Agrarian Change 13 (3): 382–404. [18] Levien, M. 2018. Dispossession Without Development: Land Grabs in Neoliberal India. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Copyright

Copyright © 2023 Bhavya Jain, Dhruv Jain, Divyansh Bhansali. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Download Paper

Paper Id : IJRASET56251

Publish Date : 2023-10-21

ISSN : 2321-9653

Publisher Name : IJRASET

DOI Link : Click Here

Submit Paper Online

Submit Paper Online