Ijraset Journal For Research in Applied Science and Engineering Technology

- Home / Ijraset

- On This Page

- Abstract

- Introduction

- Conclusion

- References

- Copyright

Birth Order Determining the Perception of Parenting Style among Female Adolescents in Relation to their Family Type

Authors: Ghausia Firoz, Farzana Alim

DOI Link: https://doi.org/10.22214/ijraset.2023.56532

Certificate: View Certificate

Abstract

The study of parenting style and practices initially focused on their influence on young children, but eventually revealed their long-term implications on an individual\'s lifetime, particularly during the crucial and transitional period of adolescence. The process of parenting is unique to each individual and varies for each child within a family. This variation may be influenced by birth order, since parents tend to behave different to each child. This is because each person\'s individuality plays a role in the interpersonal interactions they develop. The objective of this study is to examine the influence of birth order (first, middle, and last) on adolescent girls’ perception of their parents’ style of parenting, in both joint and nuclear family environments, in a comparative manner. The experiment encompasses a cohort of 100 female adolescent students, typically ranging in age from 16 to 19 years, who have exactly two siblings. The data collection instrument utilized was the Parenting Style Scale developed by Madhu Gupta and Dimple Mehtani (2017). Additionally, a self-designed questionnaire was used to gather demographic information from the participants, including age, birth order, family type, and other relevant factors. The findings indicated that eldest daughters perceived their parents as employing a democratic/authoritative parenting style, while middle-born daughters perceived their parents as employing an autocratic/authoritarian approach. On the other hand, youngest daughters perceived their parents as adopting a permissive parenting style. No significant disparity was observed in the perception of parenting styles among female adolescents from nuclear and joint family backgrounds simultaneously.

Introduction

I. INTRODUCTION

The role of parents is of utmost importance in an individual's life. The psychological well-being of children is significantly influenced by the attitudes and actions exhibited by their parents (Jordan et al., 1982). Although siblings have the same biological parents, their interactions with their caretakers exhibit distinct and varied characteristics (Adler, 1927; Sulloway, 1996). As a result, individuals have a propensity to acquire distinctive qualities, processes, and methods as a direct consequence of having distinct and one-of-a-kind experiences (Adler, 1927; Sulloway, 1996). In addition to this, research by Feinberg, Neiderhiser, Simmens, Reiss, and Hetherington (2000) found that siblings had a tendency to draw comparisons among themselves according to perceived differences in familial treatment. According to Whiteman et al. (2007), comparisons like this might result in undesirable sibling attitudes, including "hostility, competition, and unfairness. According to Jang et al. (1996), the fact that an individual is a sibling explains why each person possesses a singular and distinctive mode of communication within the context of the same family. According to Dunn and Plomin (1991), the differences that might be observed between siblings may not be the result of genetic predispositions but rather of non-shared environmental factors. Also, Plomin et al. (2001) highlighted the notion that although siblings share biological parents, their individual experiences, perceptions, and interpretations are distinct due to the influence of non-shared environmental factors. Researchers place significant emphasis on the notion that every kid is born into distinct familial circumstances, taking into consideration objective environmental variations. To provide an illustrative example, it can be seen that firstborn children tend to receive a greater amount of attention from their mothers. Conversely, at the arrival of second-born children, they are required to divide the parents' focus with their elder siblings (Lasko, 1954). From an alternative standpoint, it is often observed that parents often possess limited expertise in the realm of child raising when they welcome their first kid into the world. Nevertheless, as they proceed to have subsequent children, their understanding of child development tends to expand and become more refined. The attitudes and expectations of individuals towards their children undergo a transformation as a consequence of their own experiences (Baskett, 1985; Stewart, 2012).

Previous research has indicated that families tend to exert greater control and discipline over their firstborn children, while also assigning them a higher level of responsibility (Baskett, 1985; Hilton, 1967). According to Hoffman (1991), while examining subjective environmental factors, it has been observed that siblings exhibit varying behavioral reactions, mindsets, or lifestyles as a result of their age disparities. Therefore, while considering development, it is important to acknowledge that the way in which siblings perceive, interpret, and navigate their environment is distinct and individualized. According to Plomin, Asbury, and Dunn (2001), it has been posited that siblings may exhibit distinct personality traits akin to those of individuals from separate families. This phenomenon is attributed to non-shared factors, such as differing interpretations of experiences, sibling dynamics, and divergent family structures. While there are certain shared elements among siblings in a familial context, variations in the environment can contribute to the differentiation of siblings when it comes to their development of identity (Plomin et al., 2001). In the context of sibling relationships, it has been observed that each sibling's view of the world is influenced by their perception of one another (Hoffman, 1991). In a familial context characterized by warmth and affection, it is possible for a sibling to perceive a disparity in the allocation of parental love, leading to a diminished sense of personal affection (Hoffman, 1991). The establishment of self is significantly influenced by the process of comparing oneself to siblings, as shown by Hoffman (1991). According to Blake (1981), the resource dilution theory pertains to the phenomenon wherein an increase in the total number of siblings within a household results in a reduction in shared resources provided by parents, including physical, emotional, and psychological assistance. Hence, it may be argued that the eldest kid holds a significant advantage in terms of accessing parental resources (Ansbacher & Ansbacher, 1956; Forer, 1976). Numerous researchers have expressed apprehension over the impact of parents' perceived views on the development of distinct personality traits among siblings (e.g., Dunn & Plomin, 1991; Forer, 1976). In particular, research conducted from a developmental standpoint provides insight into the mechanisms behind the association between birth sequence and parenting styles, elucidating how this link emerges and persists. According to Harris and Howard (1985), there exists a strong association between a child's favorable view of parental attitudes and actions and their ability to recognize partiality exhibited by the parents. Additionally, Kiracofe and Kiracofe (1990) emphasized the correlation between birth order and the feeling of partiality. To provide an illustration, boys, irrespective of their birth order, have conveyed a notion of being favored by their moms. Furthermore, the eldest sons conveyed their perception of being the preferred offspring of both parents. According to Kiracofe and Kiracofe (1990), females perceive themselves as being the most favored among siblings, particularly by their dads. Chalfant (1994) also provided evidence for the notion that individuals tend to be viewed as more preferred by their parent of the opposing sex. It may be seen that men tend to perceive themselves as the favored offspring of their mothers, whereas girls tend to perceive themselves as the favored offspring of their fathers. The topic of favoritism among siblings is a subject of contention, as discussed by Rohde et al. (2003). This controversy arises from the possibility that the firstborn kid may be favored owing to their perceived reproductive value, while the later-born child may be favored due to the need for protection. In their study, Rohde et al. (2003) investigated a sample of university students from several nations, including Germany, Austria, Israel, Norway, Russia, and Spain. The primary objective of the study was to explore the effects of birth order on a range of family dynamics and relationships. The researchers reached the conclusion that those who are the youngest siblings are commonly perceived as the favored and most defiant kids within their families, as reported by both firstborn and lastborn individuals. Regarding the degree of proximity to parents, a majority of firstborn persons indicated a stronger emotional bond with their parents. Conversely, lastborn siblings tended to have a greater sense of closeness towards their elder siblings rather than their parents, regardless of the number of siblings present. Significantly, those who are middle-born had the lowest levels of emotional closeness towards their parents.

When it comes to the impacts of birth order, gender matters (Hoffman, 1991). Stereotypes and cultural beliefs are linked to gender (Brody, 1997). According to Fagot (1978), boys are given opportunities to be autonomous, whereas girls are subjected to greater behavioral feedback associated with reliance. According to Damian and Roberts (2015), men fit a conventional niche since they are more susceptible to being influenced by their parents to be more submissive and dominant. This circumstance is comparable to social and cultural conventions that force men to assume the role of responsibility. But when it comes to accomplishment expectations, parents typically have higher expectations for their daughters than for their sons (Bhanot & Jovanovic, 2005). However, in comparison with children born later, they have greater demands for the firstborn they have (Hao, Hotz & Jin, 2008).

Adolescence is a crucial period of growth on the journey to maturity, characterized by increasing independence from one's family. However, parents and other family members continue to have a crucial role in fostering the well-being of teenagers by offering a constructive support structure in which they can navigate their evolving sense of self. Currently, various sorts of family structures exist, including nuclear families, joint families, divorced families, and one-parent households. Eliot and Gray (2000) asserted that every family structure exhibits a robust connection that significantly impacts the life trajectories of its members. These relationships can be categorized as primary and secondary.

In a nuclear family, there is a primary and direct relationship involving the two generations residing together. In contrast, a joint family configuration has secondary and indirect contact with its members. Lopata (1973) asserts that family type serves numerous crucial purposes, including providing support, fostering stimulation, and facilitating strong intimacy. Both joint and nuclear family units have certain responsibilities and roles in ensuring the academic and social achievements of their children. According to Virginia Cooperative Extension (2009), family type has a significant role in creating personalities and fostering the development of life skills in adolescents. Family structure and environment have a crucial role in fostering the required confidence for academic and goal attainment in adolescents. Adolescence is a pivotal stage in the life cycle for achieving important developmental milestones. During adolescence, children have a stronger yearning for independence and spend more time with their classmates (Furstenberg, 2000). When these relationships continue to be psychologically close to parents, they remain essential resources for their children. Furthermore, fostering a favorable domestic milieu and cultivating improved familial connections can facilitate the advancement of positive personality traits and other forms of development in adolescents (Cavanagh, 2008; King et al., 2016). Adolescents continue to rely on their family as a foundation from which to venture into the world and develop independence and autonomy (Chubb & Fertman, 1992). Family members and parents can fulfill this requirement in youngsters by offering love, affection and, a nurturing home environment and authoritative parenting approaches characterized by children feeling valued and supported.

II. NEED FOR THE STUDY

For almost a century, the Indian census has consistently revealed a significant disparity in the population between males and females, both in terms of children and adults. This disparity, which has ramifications throughout the entire country, stems from choices made at the most individual level—the household. The prevailing belief is that the inclination towards having boys is driven by economic, religious, societal, and emotional aspirations and standards that prioritize males and diminish the desirability of females. This is evidently observed by children even on the basis of their birth order, on the other hand, due to known and unknown reasons. This prevalence of favoritism among Indian parents is deeply ingrained to the extent that the negative consequences of this behavior are often overlooked, instead being regarded as an inherent aspect of culture and tradition. The studies have been evident in revealing that different individuals with the same birth order tend to acquire similar traits and possess personalities that are alike. Furthermore, these parental practices can result in adolescents developing a strong aversion towards their parents, displaying attention-seeking behavior, exhibiting oppositional traits, experiencing low self-esteem, a sense of worthlessness, and even developing animosity towards their favored siblings. These negative effects may have long-lasting impacts on their personalities as they transition into adulthood. These adolescents may also exhibit excessive seeking of reassurance and frequently display vulnerability, especially girls. Therefore, the present study aids in creating transparency for the overlooked aspects of an adolescent girl’s perception of parental treatment.

III. METHODOLOGY

The birth order of the sample was the prognostic variable for the present study while the perceived style of parenting served as a dependant or response variable and to examine the data, a qualitative technique was adopted.

A. Aim

The aim of this study is to determine if the birth order and family type of female adolescents have an impact on their perception of their parents' parenting style.

B. Objective

To study the effect of birth order and family type on the perception of parenting styles of female adolescents.

C. Hypotheses

- H01: Assuming no significant correlation or effect between birth order and perceived parenting style of female adolescents.

- H02: Assuming no difference in the perceived parenting style of female adolescents of nuclear and joint family type.

D. Sample of the study

The sample consisted of one hundred female adolescent students aged 16-19 years via a stratified random sampling. The sample was deliberately selected to consist of females who had exactly two siblings in order to facilitate their classification as either firstborn, middleborn, or lastborn.

E. Procedure

Initially, the school and college administrators authorized and built a positive relationship to facilitate a direct approach toward female students. Socio-demographic data were also collected to gather the required information about the sample. The questionnaires were provided exclusively to those who were willing to participate, ensuring that consent was secured from the sample.

F. Tools used

A self-made questionnaire to obtain a socio-demographic profile of female adolescents was employed with the Parenting Style Scale (PSS) by Madhu Gupta and Dimple Mehtani (2017) that aids in estimating the perceived style of parenting. It contains 44 statements, with 4 constructs namely Democratic, Autocratic, Permissive, and Uninvolved style of parenting, having a 5-point response answer for each item. It is made suitable for adolescents in Senior Schools, Senior Secondary Schools, and Colleges.

G. Scoring

The scores are assigned based on the following scale: Always (4), Often (3), Sometimes (2), Rarely (1), and Never (0) for each item. The overall score for each parenting style is determined by summing the scores of response items associated with that style, where the parenting style with the greatest score is deemed the primary parenting style.

H. Analysis of data

The data was described by applying descriptive statistics, including frequency, mean, percentage, and standard deviation. An independent T-test was employed to compare the means of perceived parenting style of nuclear and joint family types, while Pearson's Correlation coefficient was used to determine the association between birth order and perceived parenting style. A p-value less than 0.05 was deemed statistically significant with a 95% confidence level. The data was analyzed with the IBM SPSS 25.0 software version.

IV. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

TABLE I

the frequency of the BIRTH ORDER of the sample against each parenting style.

|

Perceived Parenting Style * Ordinal Position Crosstabulation |

||||||

|

|

Birth Order |

Total |

||||

|

First Born |

Middle Born |

Last Born |

||||

|

Perceived Parenting Style |

Democratic |

Count |

31 |

27 |

25 |

83 |

|

% within PPS |

37.3% |

32.5% |

30.1% |

100.0% |

||

|

% within Birth Order |

100.0% |

73.0% |

78.1% |

83.0% |

||

|

% of Total |

31.0% |

27.0% |

25.0% |

83.0% |

||

|

Autocratic |

Count |

0 |

10 |

3 |

13 |

|

|

% within PPS |

0.0% |

76.9% |

23.1% |

100.0% |

||

|

% within Birth Order |

0.0% |

27.0% |

9.4% |

13.0% |

||

|

% of Total |

0.0% |

10.0% |

3.0% |

13.0% |

||

|

Permissible |

Count |

0 |

0 |

4 |

4 |

|

|

% within PPS |

0.0% |

0.0% |

100.0% |

100.0% |

||

|

% within Birth Order |

0.0% |

0.0% |

12.5% |

4.0% |

||

|

% of Total |

0.0% |

0.0% |

4.0% |

4.0% |

||

|

Total |

Count |

31 |

37 |

32 |

100 |

|

|

% within PPS |

31.0% |

37.0% |

32.0% |

100.0% |

||

|

% within Birth Order |

100.0% |

100.0% |

100.0% |

100.0% |

||

|

% of Total |

31.0% |

37.0% |

32.0% |

100.0% |

||

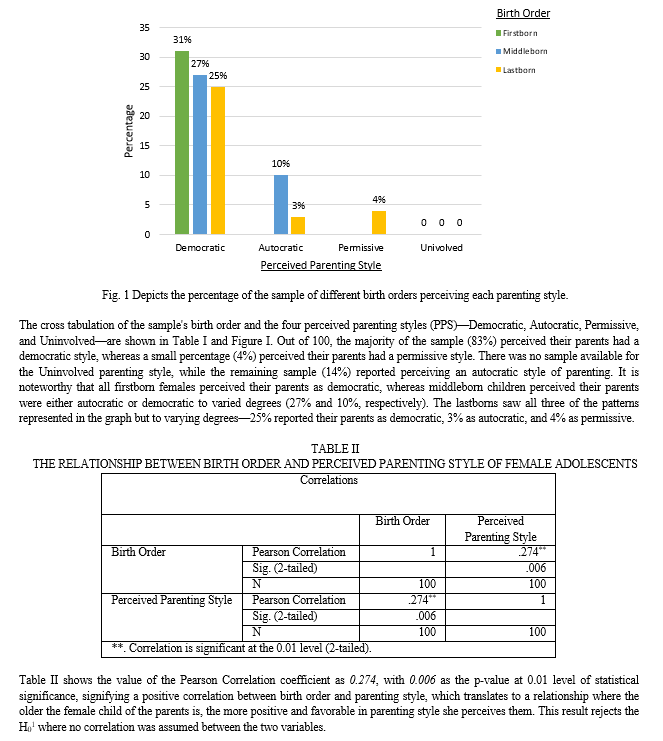

The perceived parenting styles of females in nuclear and joint family types were compared using an independent sample t-test. Female adolescents' perception of the nuclear (M=1.21, SD=0.448) and joint (M=1.21, SD=0.592) family types did not differ significantly; t(98)=0.58, p<0.05 = 0.953, where the means of both nuclear and joint family type are equal (1.21). These findings accept the H02 where no difference between the perceived parenting styles of female adolescents in nuclear and joint families was assumed.

V. LIMITATION

The problem discussed can be studied on both genders, of varying ages, on adolescents with more than 2 siblings, adolescents with a single parent, and in relation to other socio-demographic variables.

Conclusion

The topic that was researched came to the definitive conclusion that adolescent females with two siblings who occupied distinct ordinal positions in the family hierarchy had diverse perceptions of the parenting style of their parents, which shows a relationship between birth order and parenting style. The firstborn girls described their parents\' parenting style as Democratic/Authoritative, characterized by high levels of responsiveness and control. In contrast, the youngest children perceived their parents as Permissive, displaying high levels of responsiveness but lower levels of control. The middleborn girls perceived their parents as Autocratic/Authoritarian, exhibiting high levels of control but low levels of responsiveness. Fortunately, the researcher did not encounter any samples that considered parents as Uninvolved, which is characterized by low control and responsiveness. This discovery is noteworthy in itself. Moreover, no difference in the perceived parenting style was reported by the female adolescents, respective of their nuclear or joint family type.

References

[1] Adler, A. Understanding human nature. New York: Greenberg, 1927. [2] Ansbacher, H. L. & Ansbacher, R.R. The individual psychology of Alfred Adler. New York City: Harper Torch. [3] Baskett, L. M; Sibling status: Adult expectations. Developmental Psychology, 21, 441-445, 1985. [4] Bhanot, R. & Jovanovic, J. Do parents? academic gender stereotypes influence whether they intrude on their children’s homework? Sex Roles, 52(9), 597-607, 2005. [5] Brody, L. R. Gender and emotion: Beyond stereotypes. Journal of Social Issues, 53(2), 369-394, 1997. [6] Cavanagh, S. E. (2008, January 4). Family Structure History and Adolescent Adjustment. Journal of Family Issues, 29(7), 944–980. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192513x07311232 [7] Chalfant, D. (1994). Birth order, perceived parental favoritism, and feelings towards parents. Individual Psychology, 50(1), 52-57. [8] Chubb, N. H., & Fertman, C. I. (1992, September). Adolescents’ Perceptions of Belonging in Their Families. Families in Society: The Journal of Contemporary Social Services, 73(7), 387–394. https://doi.org/10.1177/104438949207300701 [9] Damian, R. I., & Roberts, B. W. (2015, October). The associations of birth order with personality and intelligence in a representative sample of U.S. high school students. Journal of Research in Personality, 58, 96–105. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2015.05.005 [10] Dunn, J., & Plomin, R. (1991, September). Why Are Siblings So Different? The Significance of Differences in Sibling Experiences Within the Family. Family Process, 30(3), 271–283. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1545-5300.1991.00271.xElliott S, Gray A. Family structures, a report for the New Zealand immigration service. Retrieved from department of labour New Zealand, 2000. website: http://www.dol.govt.nz/research/migration/pdfs/FamilySt ructures.pdf [11] Fagot, B. I. The influence of sex of child on parental reactions to toddler children. Child Development, 49, 459-465, 1978. [12] Forer, L. K. The birth order factor. New York: David McKay, 1976. [13] Furstenberg, F. F. (2000, November). The Sociology of Adolescence and Youth in the 1990s: A Critical Commentary. Journal of Marriage and Family, 62(4), 896–910. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3737.2000.00896.x [14] Hao, L., Hotz, V. J., & Jin, G. Z. (2008, March 19). Games Parents and Adolescents Play: Risky Behaviour, Parental Reputation and Strategic Transfers. The Economic Journal, 118(528), 515–555. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0297.2008.02132.x [15] Harris, I. D., & Howard, K. I. (1985, March). Correlates of Perceived Parental Favoritism. The Journal of Genetic Psychology, 146(1), 45–56. https://doi.org/10.1080/00221325.1985.9923447 [16] Hilton, I. (1967). Differences in the behavior of mothers toward first- and later-born children. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 7(3, Pt.1), 282–290. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0025074 [17] Hoffman, L. W. (1991, September). The influence of the family environment on personality: Accounting for sibling differences. Psychological Bulletin, 110(2), 187–203. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.110.2.187 [18] Jang, K. L., Livesley, W. J., & Vemon, P. A. (1996, September). Heritability of the Big Five Personality Dimensions and Their Facets: A Twin Study. Journal of Personality, 64(3), 577–592. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6494.1996.tb00522.x [19] Jordan, E. W., Whiteside, M. M., & Manaster, G. J. (1982). A practical and effective measure of birth order. Individual Psychology: The Journal of Adlerian Theory, Research, and Practice, 38(3), 253-260. [20] Kiracofe, N. M. & Kiracofe, H. N. (1990). Child-perceived favoritism and birth order. Individual Psychology: The Journal of Adlerian Theory, Research, and Practice, 46, 74-81. [21] Lasko, J. K. Parent behavior toward first and second children. Genetic Psychology Monographs, 49, 97-137, 1954. [22] Lopata H. Z. Marriages and families, 1973. Retrieved from http://www.pearsonhighered.com/assets/hip/us/hip_us_pe arsonhighered/samplechapte r/0205735363 [23] Plomin, R., Asbury, K., & Dunn, J. (2001, April). Why are Children in the Same Family So Different? Nonshared Environment a Decade Later. The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 46(3), 225–233. https://doi.org/10.1177/070674370104600302 [24] Rohde, P. Atzwanger, K., Butovskaya, M., Lampert, A., Mysterud, I., Sanchez-Andres, A., & Sulloway, F. (2003, July). Perceived parental favoritism, closeness to kin, and the rebel of the family The effects of birth order and sex. Evolution and Human Behavior, 24(4), 261–276. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1090-5138(03)00033-3 [25] Stewart, A. E. Issues in birth order research methodology: Perspectives from individual psychology. The Journal of Individual Psychology, 68(1), 76-106, 2012. [26] Sulloway, F. J. Born to rebel. New York: Pantheon Books, 1996. [27] Virginia Cooperative Extension. Families First-Keys to Successful Family Functioning: Family Roles - Home - Virginia Cooperative Extension, 2009. Retrieved on July 2, 2013, from http://pubs.ext.vt.edu/350/350-093/350- 093.html [28] Whiteman, S. D., McHale, S. M., & Crouter, A. C. (2007, October 23). Competing Processes of Sibling Influence: Observational Learning and Sibling Deidentification. Social Development, 16(4), 642–661. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9507.2007.00409.x

Copyright

Copyright © 2023 Ghausia Firoz, Farzana Alim. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Download Paper

Paper Id : IJRASET56532

Publish Date : 2023-11-05

ISSN : 2321-9653

Publisher Name : IJRASET

DOI Link : Click Here

Submit Paper Online

Submit Paper Online