Ijraset Journal For Research in Applied Science and Engineering Technology

- Home / Ijraset

- On This Page

- Abstract

- Introduction

- Conclusion

- References

- Copyright

Effect of Patriarchal Biases on Female Financial Literacy in Rural India: A Review

Authors: Devika Sardana

DOI Link: https://doi.org/10.22214/ijraset.2024.64268

Certificate: View Certificate

Abstract

In this paper, I have presented the relationship between patriarchal biases and female financial literacy in rural India. Since India is a developing country, conservative patriarchal norms, such as patrilineal and patrilocal constructs, remain a pertinent issue, especially in rural areas. These patriarchal norms also constrain economic development and female autonomy, making it a severe socioeconomic problem. Through this research, I aim to analyse the root causes of patriarchal biases and their impact on female financial literacy, while also suggesting potential methods to alleviate female financial illiteracy and bolster empowerment and economic development.

Introduction

I. INTRODUCTION

Financial literacy refers to a combination of awareness, knowledge, skill, attitude, and behaviour necessary to make sound financial decisions, ultimately achieving individual financial wellbeing (OECD, 2011). It is a vital notion for individuals to make informed financial choices, and it also contributes to various benefits such as financial security and growth. Without being financially informed, people are likely to make dangerous financial choices such as poor investments and savings, which can lead to grave consequences such as poverty and debt traps. Financial literacy is associated with a myriad of factors such as general literacy, working experience, labour force participation, and societal attitudes. General literacy enhances the quality of human capital, making highly literate workers more appealing to the labour force. Additionally, higher literacy is also correlated with higher skill and productivity. Therefore, general literacy increases one’s employability, which, in turn, leads to a gain in working experience in commercial and financial domains. Subsequently, by participating in the labour force and earning wages, workers learn to manage their finances, aiding them in internalising financial concepts such as saving, budgeting, and investing, leading to financial literacy.

Making informed financial decisions warrants financial security and access to funds, enhancing one’s living standards. Therefore, financial literacy has a significant positive effect on economic development. However, in developing countries such as India, financial literacy for women is often overlooked due to the prevalence of patriarchal constructs that suppress women’s financial autonomy. Financial illiteracy perpetuates serious social consequences for women: in patriarchal societies, women often lack access to independent funds and bank accounts (World Bank Global Findex Database, 2021), which makes them more susceptible to poverty and domestic violence given their significant reliance on male family members such as their spouses. This diminishes female autonomy and leads to social and financial disempowerment. Financial illiteracy is less pronounced in urban Indian areas due to greater socioeconomic development. Contrastingly, due to factors such as self-governing systems and conservative norms in rural areas, female financial illiteracy has persisted, which impedes rural development. Therefore, this paper attempts to address the following question: To what extent do patriarchal biases perpetuate financial illiteracy amongst Indian women from rural backgrounds? This paper provides a broad overview on this particular field of inquiry through literature review, which is applied to India through supporting data such as government reports and statistics. While previous research investigates the general causes and effects of female financial illiteracy, I investigate the problem from a socioeconomic lens, particularly in rural Indian areas – in section 2, I review literature on the origin of patriarchal biases and its subsequent effects on female financial literacy, before delving into its specific implications for rural Indian areas in section 3.

II. ORIGIN OF PATRIARCHAL BIASES & EFFECTS ON FEMALE FINANCIAL LITERACY

The following literature review presents the arguments of several research articles and studies that investigate the origin of patriarchal biases and their socioeconomic impact.

A. Traditional Agricultural Practices

Firstly, there is an observed correlation between agricultural patterns and patriarchal biases (Boserup, 1970). Differences in gender roles may be attributed to the prevalence of shifting or plough cultivation in a region. Shifting cultivation is labour-intensive and usually involves the use of simple agricultural tools such as machetes and hoes.

Contrastingly, plough cultivation is both, capital and labour intensive. Plough cultivation requires heavy machinery (ploughs) that are drawn by animals or farmers. Although plough cultivation requires less manual labour than shifting cultivation, drawing ploughs requires far more physical strength (e.g. grip and upper body strength) than working with tools such as machetes. Therefore, men are more adept at carrying out plough cultivation relative to women due to their greater grip and upper body strength (Peterson et al, 2010). Additionally, shifting cultivation requires activities such as weeding (a task requiring minimal strength, usually undertaken by women and children) to be conducted manually, whereas the process is automatic when using a plough. Therefore, regions practicing plough cultivation often employ less female labour relative to those predominantly practicing shifting cultivation.

This has an indirect effect on financial literacy. According to Frijns et al (2014), experience plays a significant role on financial literacy. The findings of this paper suggest that there is a positive and causal relationship between financial experience and financial knowledge: commercial experience enables direct exposure to financial concepts such as income management on receiving salaries, crediting, and saving, leading to enhanced financial literacy. Since agrarian economies employing plough cultivation primarily consist of a male-dominant workforce, men acquire more commercial experience than women, enhancing males’ financial literacy. This perpetuates a gap between male and female financial literacy rates as women lack financial experience, which is fundamental in being financially literate. This is also supported by the phenomenon ‘learning by doing’ (Foster and Rosenzweig, 1995). Consequently, women are compelled to undertake unpaid work such as domestic chores, which do not necessitate financial knowledge. This disincentivises them from being financially literate. Therefore, due to their lack of experience in commercial realms and consequent non-use of financial concepts, society deems financial literacy for women as inconsequential, exacerbating female financial illiteracy rates.

B. Cultural Practices

Cultural practices induce patriarchal biases that ultimately lead to a sex imbalance. According to Jayachandran (2015), patrilocal cultures often observe economic inequalities between men and women. Traditionally, when a woman marries a man, she takes on his family’s name (patrilineality) and relocates to his home (patrilocality), ceasing to be a member of her own birth family. Due to this framework, parents tend to invest more in the health and education of sons rather than daughters as sons continue the legacy of their birth families, whereas daughters sever familial ties with their original households upon marriage. This larger investment in male human capital perpetuates a gap between women’s and men’s general literacy rates and living standards, causing women to be underserved. Patrilocal cultures, thus, enhance male economic mobility, making them more desirable than women to labour markets. This invariably restricts women’s financial experience, leading to female financial illiteracy.

Patrilineal cultures are also responsible for hampering women’s financial autonomy and security. In patrilineal systems, since assets such as properties are inherited by the male descendants of the family (Jayachandran, 2015), society favours sons over daughters. Consequently, since women do not carry their family’s legacy and are deprived of opportunities to manage assets and wealth, female financial literacy is considered futile, perpetuating female financial illiteracy. The combination of patrilocality and patrilineality also give rise to the concept of “missing women” (Sen, 1990). “Missing women” refers to the sex imbalance experienced by developing countries (Anderson and Ray, 2010). Due to the benefits received by sons in patrilocal and patrilineal systems, sons are preferred to daughters. The preference of sons is also exemplified by dowry systems, wherein a bride’s family make payments to the groom’s family at the time of marriage, serving as the “price” for the groom. Dowries, hence, exacerbate the financial burden on brides’ families, while monetarily rewarding grooms’ families. Consequently, this creates a bias against females in patriarchal societies, undermining their socioeconomic standing. This also perpetuates female infanticide – one of the root causes for the male-skewed child sex ratio. Moreover, prenatal sex determination technologies and selective abortion of female foetuses aggravate the sex imbalance, subsequently causing society to overlook women and deprive them of the same economic opportunities as men. Therefore, the concept of “missing women” shows how society undervalues women, discouraging parents from investing in female human capital and essentially reducing women’s general literacy and financial literacy rates.

C. Ancient Texts and Religious Constructs

Additionally, ancient texts and traditions, too, play a significant role in the emergence of patriarchal biases. The ‘Vedas,’ originated in India, are one of the earliest religious texts, which govern the religion of Hinduism. These influential texts gave rise to the Vedic period (c. 1500–500 BCE), during which ancient Indian society adopted male-dominant religious rituals. For instance, it was to be a son who lit a deceased person’s funeral pyre and brought their salvation, engendering a preference for sons. The Vedas, also, gradually evolved into texts like the ‘Manusmriti’ (c. 2nd century BCE to 3rd century CE), which authorised a more rigid patriarchal social order.

By prescribing distinct roles and duties for men and women, these texts gave rise to female subordination and male dominance. For example, the Manusmriti glorifies the role of women as wives and mothers – it conveys that the ideal wife is an obedient woman dedicated to household chores and is, thus, advised to stay indoors and take on familial responsibilities (N. M. and Kuruvilla, 2022). Contrastingly, men are characterised as the breadwinners of the household. These preachings paved the way for gender stereotypes, restricting women and confining them to unpaid domestic work. This prevents them from joining the labour force, curtailing financial experience and literacy.

Similarly, religious constructs also contribute to patriarchal biases and female subordination. For example, in Christianity, clerical hierarchies exclude women from priesthood and several other Christian denominations. This prevents women from obtaining high-paying, influential roles within the church, disadvantaging them socioeconomically. Additionally, the New Testament emphasises the role of women as wives and mothers, while men are characterised with leadership and responsibility. This notion of women as homemakers is also encouraged in Hinduism, discouraging them from seeking education and employment outside the home. This causes women to be financially and economically reliant on their husbands, exacerbating their economic dependency and financial illiteracy. Moreover, Hindu and Islamic inheritance laws often favour male heirs (patrilineality), causing smaller shares of inheritance to be allocated to women in comparison to men, thereby hampering their financial independence and security. Islamic ‘Sharia’ laws often require women to have a male guardian's permission to work or access education, perpetuating a patriarchal power dynamic. Their permission, thus, has a direct impact on female labour force participation (FLFP) and financial literacy rates. Additionally, Christianity and Hinduism express the desire to preserve female “purity” by disparaging premarital sex. This is often achieved by enforcing constructs that minimise women’s contact with all men except their husbands (Field, Jayachandran, et al, 2010). Examples of preventing women’s sexual interactions with men entail discouraging women from taking external jobs and compelling to them to undertake domestic chores. These practices, thus, lock women into a misogynistic equilibrium, which is sustained by religious and cultural norms that often become formal legislation (e.g. patrilineal inheritance laws). This invariably curtails women’s financial exposure and literacy.

III. IMPLICATIONS OF FINDINGS ON RURAL INDIAN WOMEN WITH SUPPORTING DATA

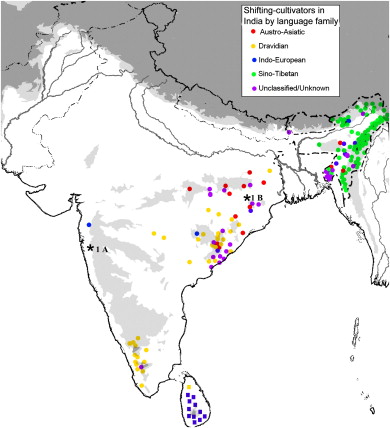

This correlation between patriarchal biases and agricultural style can be generalised to rural areas in India as the dearth of skilled workers in rural economies compels them to undertake primary sector activities – namely farming. Consequently, states such as Haryana, which historically relied on plough agriculture, exhibit lower FLFP rates (14.7%) than states such as Nagaland (31.1%), which primarily practiced shifting cultivation [Figure 1]. Although the leading agricultural style varied from region to region [Figure 2], plough cultivation was the most common agricultural style. Shifting cultivation was commonly practiced in northeast India due to its hilly terrain. The greater majority of India has a planar or rocky terrain, supporting plough agriculture. The widespread use of plough agriculture for centuries contributed to the male-dominant workforce in rural India which, in turn, perpetuated patriarchal social norms that have persisted in contemporary times.

Figure 1: State Comparison of Female WPR in India (FLFP)

|

State |

Female WPR (Worker Population Ratio) |

|

Bihar |

9.4% |

|

Uttar Pradesh |

17.2% |

|

Haryana |

14.7% |

|

Nagaland |

31.1% |

|

Ladakh |

51.1% |

|

Himachal Pradesh |

63.1% |

|

Delhi |

14.5% |

|

Sikkim |

58.5% |

|

All India (Mean) |

28.7% |

Source: Press Information Bureau Government of India Ministry of Agriculture & Farmers Welfare (2022)

Figure 2: Indian Regions Predominantly Practicing Shifting Cultivation

Source: Shifting cultivators in South Asia: Expansion, marginalisation and specialisation over the long term (2012)

This correlation is beneficial in understanding the roots of patriarchal biases in India as historically, agriculture contributed to a significant proportion of the Indian GDP (41.7% in FY 1970). However, since then, the share of agriculture in India’s GDP has fallen to about 14.4% in FY 2010 due to industrialisation [Figure 3]. Despite the decline in agriculture, and concomitant fall in plough cultivation, the gap in female and male literacy rates has continued to persist [Figure 4]. This indicates that while secondary and tertiary sectors have grown rapidly, it is difficult to change primitive societal attitudes (stemming from agricultural practices) at the same rate.

Figure 3: Share of Agriculture Sector in Indian GDP

|

Year |

GDP SHARE OF AGRICULTURE TO TOTAL ECONOMY – at 2004-05 prices (%) |

|

1960-61 |

47.6 |

|

1970-71 |

41.7 |

|

1980-81 |

35.7 |

|

1990-91 |

29.5 |

|

2000-01 |

22.3 |

|

2010-11 |

14.4 |

Source: Press Information Bureau Government of India Ministry of Agriculture & Farmers Welfare (2011)

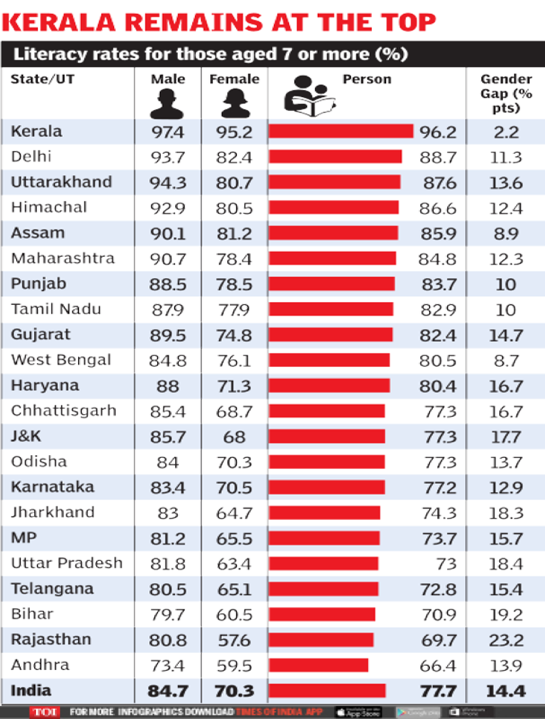

Figure 4: Literacy Rates for Indian States

Source: NSO (National Statistical Office), 2017-18

However, a limitation of this correlation is that causation cannot be established between traditional agricultural style and female financial literacy as several confounding factors (such as religion) may also correlate with traditional agricultural style. There are also several exceptions – states such as Kerala [Figure 4] that predominantly practice plough cultivation report the highest female literacy rates and the lowest gender gaps. This presents a weakness of this correlation as not all regions adhere to the inverse relationship between plough cultivation and female financial literacy.

Furthermore, the effects of cultural and religious factors play a significant role in Indian societies. Due to the religious diversity in India (ranging from Hinduism, Sikhism, Islam, and Christianity), the effects of religious beliefs are especially pronounced in rural areas given the presence of conservative, self-governing systems such as the ‘Gram Panchayat.’ These self-governing systems in rural areas are subject to enforce patriarchal social order due to rural underdevelopment, hindering social and economic progress. Contrastingly, the socioeconomic effects of religious constructs are less prominent in urban areas due to secularism, which is exercised by the state.

Hence, rural areas are more prone to adopting patrilocal and patrilineal systems, perpetuating more male-skewed sex ratios [Figure 5] and female subordination, causing female financial illiteracy (Jayachandran 2015). This is also supported by Dyson & Moore (1983), wherein it is noted that the northern region in India has a stronger patrilocal (and patrilineal) system than the south, which is one explanation for why gender inequality is more pronounced in the north. This is reinforced by Figure 4, which indicates that the northernmost state (Jammu and Kashmir) reports a gender gap of 17.7% in comparison to 2.2% in Kerala, a southern state. Although Figure 4 addresses general literacy, gender gaps in general literacy also indicate gender gaps in financial literacy due to their strong positive correlation: greater literacy increases the employability of labour, which increases their working experience and, invariably, their financial literacy. Literacy also promotes more analytical financial decisions, improving financial skill and security. Additionally, since literacy is a primary educational investment in human capital, it is followed by other forms of human capital accumulation such as financial literacy.

Figure 5: Child Sex-Ratio at Birth in Indian States

|

State/UT |

Child Sex Ratio (age 0-6 years) |

|

Bihar |

916 |

|

Goa |

774 |

|

Himachal Pradesh |

882 |

|

Kerala |

967 |

|

Meghalaya |

982 |

|

Mizoram |

1007 |

|

Nagaland |

949 |

|

Sikkim |

962 |

Source: Ministry of Health and Family Welfare (2021)

Conclusion

In conclusion, patriarchal biases and female financial illiteracy have a strong positive correlation. During this investigation, I also examined the potential bidirectional ambiguity – does female financial illiteracy also contribute to patriarchal biases and not only vice versa? However, given the aforementioned arguments, it is evident that patriarchal biases have always preceded female financial illiteracy (e.g. ancient scriptures). Therefore, the relationship between patriarchal stereotypes and female financial literacy is unidirectional, with patriarchy inducing female financial literacy. Female financial illiteracy is a significant problem as it hinders economic progress: due to high restrictions placed on women entering the labour force, India’s productive potential is diminished as women, as human capital resources, are underemployed or unemployed. Market reforms enabling women to enter the labour market will be beneficial for the Indian economy as the quantity of resources (human capital) will increase, leading to an increase in potential output and long-term economic growth. Women can be instrumental in bolstering the economy, especially due to the growth of the tertiary (service) sector. This is supported by the OECD’s Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) regular evaluation of the educational performance of 15-year-old students across various countries. The 2018 PISA results indicate that females outperform males in reading and tend to perform equally well in science and mathematics. These findings suggest that females often excel in certain intellectual domains, showing that women are well-equipped to work as skilled labour in the tertiary sector. This will also generate more employment opportunities in the economy, reducing the government’s financial burden of providing transfer payments such as unemployment benefits. Ultimately, with extensive commercial experience, women will effectively manage their own finances while saving and investing, leading to enhanced financial literacy and autonomy, uplifting living standards. This will also alleviate those trapped in absolute or multidimensional poverty cycles. The Indian government has introduced various reforms that enable women to participate in the workforce such as Pradhan Mantri Jan Dhan Yojana (PMJDY). PMJDY aims to provide universal access to banking facilities, with a focus on opening microfinancing institutions and bank accounts for women. The scheme includes financial literacy programs to educate women on banking services, savings, credit, insurance, and pensions. Additionally, the Beti Bachao Beti Padhao (BBBP) scheme also includes components of financial literacy, helping young girls and their families understand the importance of financial planning and management. Since literacy rates directly improve human capital, women are more economically able and mobile, leading to further working experience and financial literacy. However, since female financial illiteracy is largely owed to patriarchal biases, there must be reforms in cultural practices, especially in rural areas. While economic policies may become more flexible in regard to women joining the workforce, it is difficult to change the deep-rooted, conservative mindset of society. Therefore, the government must also introduce social policies such as awareness creation to promote the significance of female financial literacy and the positive contributions they can make to the Indian economy.

References

[1] Alesina, Alberto, et al. “ON THE ORIGINS OF GENDER ROLES: WOMEN AND THE PLOUGH.” The Quarterly Journal of Economics, vol. 128, no. 2, 2013, pp. 469–530. JSTOR, https://www.jstor.org/stable/26372505. [2] FRIJNS, BART, et al. “Learning by Doing: The Role of Financial Experience in Financial Literacy.” Journal of Public Policy, vol. 34, no. 1, 2014, pp. 123–54. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/43864456. [3] Foster, Andrew D., and Mark R. Rosenzweig. “Learning by Doing and Learning from Others: Human Capital and Technical Change in Agriculture.” Journal of Political Economy, vol. 103, no. 6, 1995, pp. 1176–209. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/2138708. [4] Peterson, Erin; Murray, Will; Hiebert, Jean M. “Effect off Gender and Exercise Type on Relative Hand Grip Strength.” Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 24():p 1, January 2010. | DOI: 10.1097/01.JSC.0000367192.78257.72 [5] Leur, Alette van. “The Rural Economy: An Untapped Source of Jobs, Growth and Development.” International Labour Organization, 13 Mar. 2017, www.ilo.org/resource/article/rural-economy-untapped-source-jobs-growth-and-development#:~:text=Rural%20economies%20remain%20largely%20associated,mandate%20of%20ministries%20of%20labour. [6] N. M., Naseera and Kuruvilla, Moly (2022) \"The Sexual Politics of the Manusmriti: A Critical Analysis with Sexual and Reproductive Health Rights Perspectives,\" Journal of International Women\'s Studies: Vol. 23: Iss. 6, Article 3. [7] Field, Jayachandran, et al. “Do Traditional Institutions Constrain Female Entrepreneurship? A Field Experiment on Business Training in India.” The American Economic Review, vol. 100, no. 2, 2010, pp. 125–29. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/27804976. [8] Jayachandran, Seema. “The Roots of Gender Inequality in Developing Countries.” Annual Review of Economics, vol. 7, 2015, pp. 63–88. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/44860742. [9] AROKIASAMY, PERIANAYAGAM, and SRINIVAS GOLI. “Explaining the Skewed Child Sex Ratio in Rural India: Revisiting the Landholding-Patriarchy Hypothesis.” Economic and Political Weekly, vol. 47, no. 42, 2012, pp. 85–94. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/41720276. [10] Hung, Angela, et al. “Empowering Women through Financial Awareness and Education.” OECD iLibrary, OECD, 1 Mar. 2012 [11] K, Prameela. “Rural India: Patriarchal Influences in Local Self-Governing Bodies Hinders Genuine Progress.” The New Indian Express, 20 Aug. 2023, www.newindianexpress.com/opinions/2023/Aug/19/rural-india-patriarchal-influences-in-local-self-governing-bodies-hinders-genuine-progress-2606908.html.

Copyright

Copyright © 2024 Devika Sardana. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Download Paper

Paper Id : IJRASET64268

Publish Date : 2024-09-18

ISSN : 2321-9653

Publisher Name : IJRASET

DOI Link : Click Here

Submit Paper Online

Submit Paper Online