Ijraset Journal For Research in Applied Science and Engineering Technology

- Home / Ijraset

- On This Page

- Abstract

- Introduction

- Conclusion

- References

- Copyright

Gender and the Gig Economy: An Analysis of Women Workers across Gig Platforms

Authors: Tarun Bansal, Dr. Swarita De

DOI Link: https://doi.org/10.22214/ijraset.2024.64178

Certificate: View Certificate

Abstract

The expansion of gig economy was seen with short term, flexible work along with the benefit of digital platforms, all these have brought in new opportunities for people. The main idea of the passage is to explore participation, the hindrances and the discrimination they must go through It also studies the issues and societal factors contributing to the \"missing women\" phenomenon in India. The research paper uses secondary data and a more qualitative approach along with some analytical tools such as linear regression, and chi-square to test the hypotheses and find conclusions. The analysis concludes that women are often disregarded in the gig platforms and tend to engage in lower paying jobs with lesser flexibility for them. Additionally, women experience unequal pay, unstable job, and lesser of benefits in the gig economy. With respect to the \"missing women\" phenomenon in India, the study explores behavioural factors such as son preference, gender inequality practices. By finding the gaps and challenges faced by women, which are often ignored, this study aims to inform policies and practices that can help women overcome obstacles, promote gender equality, and create a more inclusive and equitable gig economy.

Introduction

I. INTRODUCTIONS

The gig economy is mainly defined by freelance work and short-term contracts rather than permanent employment. The surge in the gig economy has been boosted by digital platforms that link workers with clients for services like ride-hailing, meal delivery, and house cleaning. We have witnessed a shift from traditional labour markets to gig platforms through new opportunities for workers, especially through platforms such as Uber or Instacart etc. The gig economy comes with its own challenges.

The research papers examine the experiences of different groups within the gig economy, particularly women. Although women make up 50% of the global workforce, but they are still faced with obstacles and barriers to achieving equality. The gig economy might provide solutions to some of these issues by offering flexible work schedules and additional income opportunities. However, it also risks deepening existing gender disparities, especially regarding pay and job stability. The paper aims to analyse the gender dynamics of the gig platform. This analysis will be supported by current literature and data on the gig economy and gender.

It is indicated that freelance workers find work independently and are restricted to limited labour protections such as minimum wage laws and unemployment insurance. (Zipperer et al., 2022). Additionally, data from the JPMorgan Chase Institute reveals that female gig workers earn 7% less per hour than their male counterparts (JP Morgan, 2018).

The aim of the research is to find the challenges and obstacles faced by women in the gig platform during their lifetime. This study seeks to inform policies and initiatives aimed at enhancing gender equality in this rapidly evolving sector. The goal is to ensure that women can fully participate, freely and independently, from the gig economy and achieve equality.

II. LITERATURE REVIEW

There has been an increase in the employment rate and opportunities in the gig economy. There has been an increase in alternative work arrangements, from 10.7% in 2005 to between 14.5% by the year 2015 (RAND-Princeton Worker Survey, and Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2005). Notably, around 0.5% of workers in 2015 reported using online platforms like Uber or TaskRabbit for work, reflecting a rapid expansion (Katz & Krueger, 2016). But with the growing economy there has been a debate that whether they benefited the women or not. Research on over a million Uber drivers in the U.S. found a 7% gender earnings gap, explained by factors such as experience on the platform, work location choices influenced by safety and residential areas, and driving speed preferences. But there were not many differences found in work hours or intensity. The study suggests that gender pay gaps in the gig economy are sustained by differences in non-paid work time costs and gender preferences and constraints (Cook et al., 2020).

In India, women’s participation is mainly in freelancing and micro-tasking which comes with many adverse challenges such as backward technology, low literacy and bad societal norms which impede their participation and advancement (NIPFP, 2019; Ghosh et al., 2022). Policies should aid women empowerment by focusing more on skill development, less discriminatory practices, access to finance, and support systems like childcare (ODI, 2020). The OECD emphasizes the need for stronger anti-discrimination laws and regulations to address gender-based pay gaps and workplace harassment (OECD, 2021).

Women in India are usually engaged in activities like caregiving and cleaning work. Due to the lesser opportunities, women often get low earnings, less security and extra challenges showcasing their skills. Many women turn to the gig economy due to non-work schedules, such as childcare and family responsibilities. Policies supporting women in the gig economy should address gender pay gaps, improve protections and benefits, and promote equal opportunities across all tasks (Churchill & Craig, 2019; Hunt & Samman, 2019). In India, the female is to male sex ratio underscores severe gender inequality and neglect, driven by cultural preferences for sons and the dowry system. In many places in India people still prefer male child leading to abortions and female foeticide. The policies shall also focus on throwing away son preference, this can be done through education and empowering women and making policies. Enforcing gender equality laws and promoting education and equal opportunities for girls are crucial (Saikia, 2015; Probst, 2009). According to NITI Aayog the total workforce participation rate was over 7.5 million with the number increasing to 23.5 million. Despite such a high growth rate women’s participation remains stagnant at 28%. Challenges stem from a lack of targeted policies and insufficient social security benefits. Solutions include creating more online work opportunities and providing better support during disputes (Kasliwal, 2020; Barzilay & Ben-David, 2016).

The gig economy's growing prominence highlights workers' appreciation for the control it offers over their careers Establishing essential connections—suitable workspaces, productive routines, a purpose linking personal interests with societal needs, and a supportive network—helps freelancers manage productivity and anxiety (Petriglieri et al., 2018).

III. RESEARCH OBJECTIVES

By identifying structural biases and inequalities, the study seeks to offer strategies for creating a more equitable gig economy. At the end, the benefit of the research should be to women workers in the gig platform and assist the policymakers.

Considering the broad field of study, the specific objectives of this paper are as follows:

- To examine the participation, challenges, and discrimination faced by women in the gig economy and identify the best policies to support their advancement.

- To investigate the systemic challenges and societal factors contributing to the phenomenon of missing women in India

IV. RESEARCH METHODOLOGY

The objective of the study is to find the working of gig economy with focus on female participation along with their challenges such as wage inequality, working condition and low benefits. For the analysis a qualitative approach along with various statistical tools has been selected. The paper aims to find relevant data which will be beneficial for policymakers.

The acquired data will be analysed using statistical tools such as inferential statistics, regression analysis, and chi-square testing to test hypotheses and find significant connections between variables. By highlighting the difficulties and possibilities women encounter in this field, this study hopes to help researchers better understand how the gig economy affects women workers. The first objective has been divided into three subparts for better analysis, i.e. (i) Participation, (ii) Challenges and (iii) Discrimination

V. FINDINGS AND ANALYSIS

Based on Objective 1: To examine the participation, challenges, and discrimination faced by women in the gig economy, and identify best policies to support their advancement.

1) Participation

Null hypothesis (1H0): There is no significant difference in the participation rates of men and women in the gig economy.

Alternative hypothesis (1Ha): There is a significant difference in the participation rates. Women are more likely to engage in lower-paying and less flexible types of gig work.

2) Challenges

Null hypothesis (2H0): There is no significant difference in the pay, job security, and benefits of men and women in the gig economy.

Alternative hypothesis 2(Ha): Women experience pay disparities, job insecurity, and lack of benefits in the gig economy compared to men.

3) Discrimination

Null hypothesis (3H0): There is no significant association between gender discrimination/bias and women's experiences in the gig economy.

Alternative hypothesis (3Ha): Gender discrimination and bias negatively affect women's experiences in the gig economy, resulting in lower pay and fewer opportunities.

Based on Objective 2: To examine the systemic challenges and societal factors contributing to the phenomenon of missing women in India.

Null Hypothesis (4H0): No phenomenon of missing woman occurring in India.

Alternative Hypothesis(4Ha): There is a phenomenon of missing woman occurring in India.

A. Objective 1

1) Hypothesis 1

According to Taskmo data, the rise of the gig economy has resulted in a major shift in women's labour force participation. There has been an increase in the number of women applying for gig jobs in the last six months, with the majority coming from urban and Tier 1 locations. Furthermore, the finance, edtech, ecommerce, fashion tech, and health tech industries are leaders in job allocation for female gig workers. This paradigm shift in women's engagement in the freelance economy can be linked to the industry's flexibility and ease. Furthermore, the Covid-19 epidemic has played a key impact in pushing women towards gig work, as traditional employment prospects became limited during the pandemic's economic crisis. A significant growth in the number of women participating in the gig economy from Tier 2 and Tier 3 cities is also remarkable. This trend implies that women from all socioeconomic groups are becoming more aware of and accepting contract work. The increased participation of women in the gig economy represents a significant shift in the labour market that has the potential to benefit both individuals and the industries they serve. This trend is expected to continue in the future: women wanting greater flexibility and control over their work-life balance are increasingly turning to the freelancing economy.

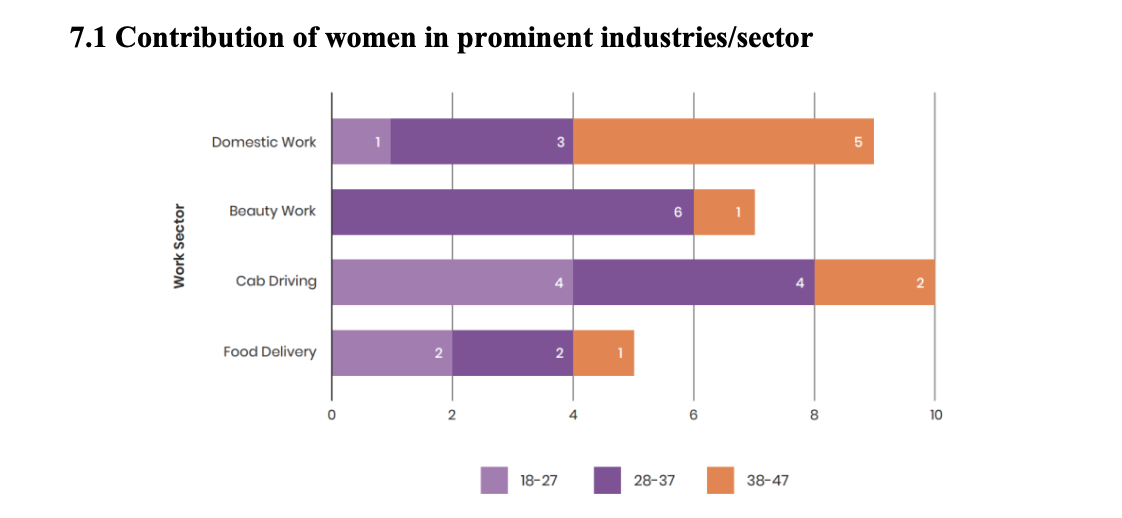

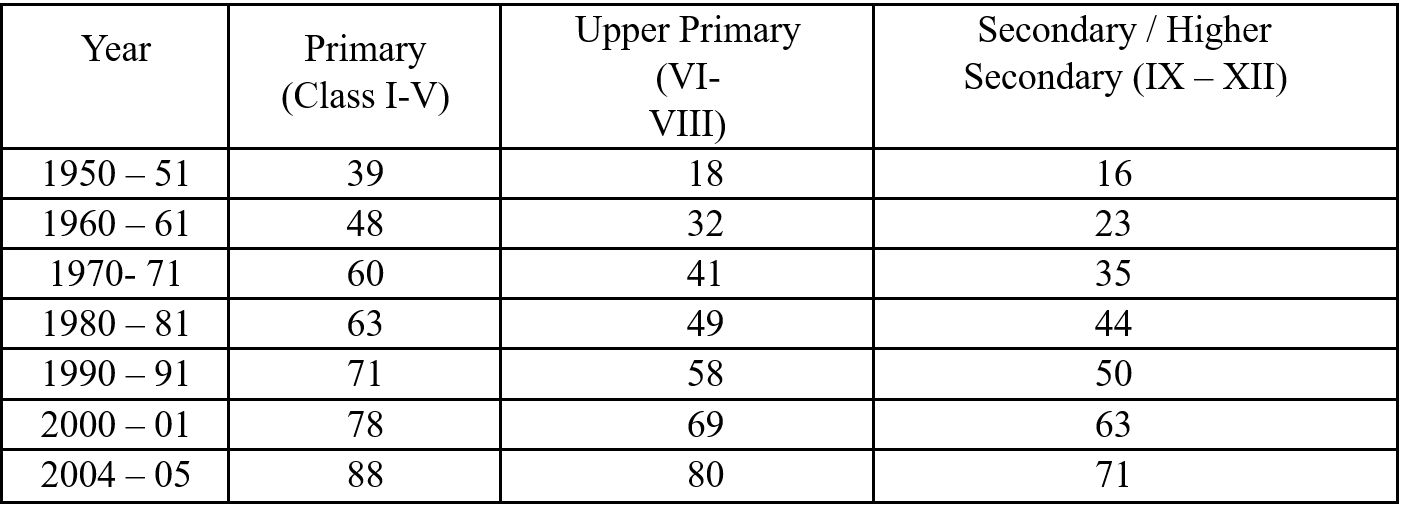

Figure 1: Contribution of women in prominent industries/sector

Source: Ghosh, Ramachandran, and Zaidi, 2021

Source: Ghosh, Ramachandran, and Zaidi, 2021

According to Figure 1, most respondents were between the ages of 28 and 37. Most responders aged 18 to 27 worked as food delivery workers or taxi drivers. The major criteria in the food delivery industry were a valid driver's license, and we noticed that many of the young women who joined these platforms to augment their income were students. In the instance of taxi driving, young women were eager to learn a new skill that would give them more power. The study discovered that in the absence of a primary male breadwinner in the household, women typically entered domestic labour, taxi transportation, and food delivery partnerships.

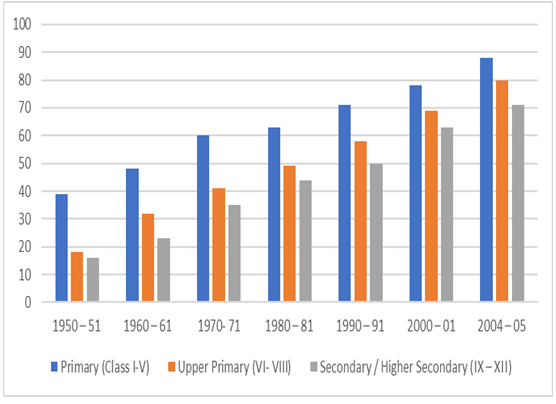

Figure 2: Ratio of unpaid work undertaken by men and women respectively

Source: Ghosh, Ramachandran, Zaidi, 2021

The socio-cultural norm in the society hampers the women’s mobility. There is an unequal distribution of household work. Women are made to do all the chores around such as cleaning, cooking and looking over children, along with attending to the elders. All these chores are unpaid for women and is viewed as women’s responsibility. On a global scale, women contribute far more to unpaid caregiving than males, particularly where state or other institutional care facilities are unaffordable or unavailable. According to a McKinsey analysis, around 68% of women globally are active in domestic tasks (compared to 32% of men), car work, and other unpaid work, however in India, 87% of women are engaged in unpaid labour compared to 13% of males. Women with a high burden of household responsibilities frequently seek professional possibilities that allow them a certain amount of freedom and flexibility, such as work that keeps them close to their families, to balance their economical and non-economical duties.

2) Hypothesis 2

The second objective of this study was to explore the challenges faced by women workers in the gig economy, including pay disparities, job insecurity, and lack of benefits. To accomplish this objective, we utilised the Chi-Square test to examine the correlation between gender and income in the gig economy. This was accomplished using Excel, and the table from which the values were derived is provided below:

Table 1: Relationship between income in Gig Economy and gender disparities

|

Chi – Square |

23.63 |

|

P – Value |

0.0095% |

Source: Based on author’s calculations between gender ratio and income

We obtained the raw data on the incomes of men and women in the informal sector of several nations from a website called "ILOSTAT". According to the data, women in the freelance economy earn less than men, which is consistent with previous research also mentioned in our literature review on gender disparities in the labour market. The Chi-Square statistic was 23.63, which is greater than the critical value for a Chi- Square distribution with one degree of freedom and a significance level of 0.05. Chi- Square was calculated using the formula

This indicated that the observed frequencies of income for men and women in the gig economy differ considerably from the expected frequencies, indicating a strong correlation between gender and income.

Assuming that there is no association between the two variables, the p-value is the probability of obtaining the observed data or more extreme data. The calculated p-value, 0.0095, is significantly lower than the cut-off of 0.05. The strong association helps to conclude that women face pay disparities, job insecurity, and a lack of benefits. There are multiple possible causes for these challenges. First, women may be more likely to work in lower paying gigs and underpaid jobs and sectors of the gig economy, such as domestic work or care work. Secondly, women in the gig economy may face discrimination and bias during the hiring and promotion processes. Thirdly, additional obstacles, such as a lack of access to technology or financing, may prevent women from participating in higher-paying gigs. Lastly, women may be more likely to encounter obstacles such as caregiving responsibilities and lack of access to transportation, which may limit their ability to work occupations or industries. To corroborate our findings, we also perused websites that offered similar insights. The authors of the World Economic Forum study emphasise that self- employed women confront a gender pay gap that is nearly three times greater than those in full-time employment. Despite the excruciatingly slow progress many companies have made in addressing salary disparities, this is the case. These were their findings:

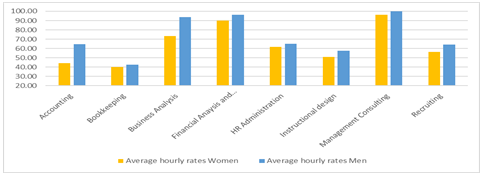

Figure 3: Gender Disparities in the Gig Economy based on income.

Source: Adapted from World Economic Forum, 2022

In conclusion, based on the results of the Chi-square test, that the null hypothesis has been rejected and the alternative hypothesis is supported. This means that men and women in the gig economy have significantly different pay, job security, and benefits. Thus, the Chi-square test results support the conclusion that there is a significant difference in the pay, job security, and benefits of men and women in the contract economy, and that women face challenges that require policy interventions. Figure 3 showcases the difference in pay that the women receive against that of the men, which is higher in all the major jobs.

3) Hypothesis 3

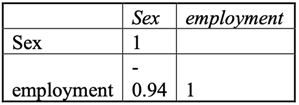

The correlation research revealed a substantial negative association between gender and employment levels in the context of India's gig economy, with a negative "r" value of -0.94.

Table 2: Gender Disparities in the Gig Economy based on employment.

Source: Based on regression run by author between employment level and gender ratio

The intensity and direction of the linear link between two variables are measured by the correlation coefficient, or "r." The two factors in this situation are employment levels and gender. The value of the other variable (employment levels) falls as the value of the first variable (in this example, gender) grows, according to a negative correlation coefficient. The two variables are therefore going in opposing directions.

The chi-square test suggest that employment levels are more favourable towards men and the employment levels fall when the gender ratio favours women. This tells that women face difficulties in securing jobs due to the gender discrimination and the platforms preferring men.

Several research papers that are also mentioned in the literature review have shown that gender discrimination may manifest itself in the workplace in several ways, including unequal compensation, biased hiring practises, and few prospects for professional advancement. These can be some major reasons of increase in the number of men in the labour workforce. Due to a variety of circumstances, including professional segregation, gender stereotyping, insufficient access to finance, and a lack of support, women encounter gender prejudice in the gig economy. For instance, discrimination against women may occur during the recruiting process and during promotions, resulting in lower pay and less opportunities for professional advancement. The mentioned challenges may significantly discourage women to participate more. As also mentioned in the second objective of this study, women may also be forced into less respectable gig jobs like domestic or care work due to the social norms and stereotypes. Often in the gig economy, the roles of male and female are divided into segments. In low-paying gig professions that are perceived as usually feminine, such cleaning, personal care, and babysitting, women are frequently overrepresented. On the other hand, males are more likely to work in higher paying, traditionally masculine fields. The gender pay gap that results from this segregation limits women's earning potential in the gig economy. The gender-based segregation of labour in the gig economy is another feasible explanation for the inverse relationship between gender and employment levels found in the negative correlation test done. As domestic and care jobs are frequently underpaid and undervalued in compared to other sorts of employment, women are more likely to specialise in these types of gig work. As a result, women could have a harder time finding work in the gig economy, which would help explain the inverse relationship between gender and employment rates.

Additionally, authorities, employers, and peers may not provide enough support for women working in the gig economy. For women, networking and mentorship options can be limited, and they might not have access to advocacy or legal tools to deal with harassment or discrimination. The gig economy is typically viewed as a flexible work environment where employees may choose their own hours and work from home. Women with additional caring and domestic responsibilities, however, could find this flexibility limited. Women may struggle to balance their various obligations with gig economy jobs, which limits their ability to make more money. Throughout the gig economy, gender stereotypes that prevail in general culture are ubiquitous. Women may be perceived as less talented and enterprising than males, which limits their possibilities for growth in the gig economy. Also, it may be difficult for women to thrive in these professions if they work in industries where males typically hold most of the positions.

Based on the analysis provided by the correlation test, the null hypothesis can be rejected in favour of the alternative hypothesis. Women are underrepresented in the gig economy compared to males, as indicated by the negative correlation between gender and employment levels. The alternative hypothesis is supported by the results of the analysis, which indicate that women encounter different difficulties in the gig economy than men. These results emphasise the need for policies and interventions to address gender disparities and promote gender equality in the labour economy.

B. Objective 2: Missing Woman Problem in India

The UNDP report suggest that approx. 85 million of the totals of around 100 million missing women were found from India and China. The term “missing women” refers to women who are not able to participate or have died due to discrimination, lack of healthcare facilities or were never born. Amartya Sen has argued that India is responsible for 32 million of these missing women. The adverse sex ratios in India suggest a form of gender biasness conspiracy gradually eliminating the female population. India’s sex ratios are highly unfavourable. The female ratio was 927 per 1,000 males in 1990, and it increased to 940 in 2011. India is still very much behind the world average of 990. Comparing that with the other developed nations, Russia had 1100, Japan had 1040 whereas USA had 1029. The female ratio is even worse for the 0-6 age group i.e. 914 for every 1000 males. This ratio dropped by 1.40% over the previous decade, even as the overall sex ratio in India improved by 0.75%. Table 3 illustrates the state-wise changes in the child sex ratio from 2001 to the year 2011.

Table 3: State wise Change in Child Sex Ratio from 2001-2011

Source: Census report 2011

Table 3 illustrates the child sex ratio (CSR) in various Indian states according to the 2011 census. Mizoram has the highest ratio, with 971 girls per 1,000 boys, followed by Meghalaya and the Andaman & Nicobar Islands with 970 and 966 girls respectively. States with the poorest ratios were Haryana at 830 girls per 1,000 boys, followed by Punjab at 846 and Jammu & Kashmir at 859. Although, Punjab exhibited the most significant improvement in the child sex ratio, increasing by 6.02% over the decade. In contrast, Jammu & Kashmir saw a drastic decline of -8.71%, reducing its ratio from 941 to 859 girls per 1,000 boys. Over the past ten years, only six states and two union territories out of a total of 35 in India experienced a rise in the child sex ratio. Among these, only four regions had an increase greater than 1%: Punjab (6.02%), Chandigarh (UT) (2.60%), Haryana (1.34%), and Himachal Pradesh (1.12%). These figures highlight the ongoing gender imbalance in India, contributing to the 'Missing Women' issue.

The problem of missing women arises from severe gender disparity. This can be understood through various factors:

- Increase in Female Feticide: In many regions of India, people still prefer male child leading to abortion of females.

- Ratio of Girls to Boys Born: The natural ratio is imbalanced due to people still preferring male boys. People abort the female child

- Difference in Mortality Rates: India is still very behind in healthcare facilities, especially in the rural region, and people are not able to provide nutrition to the babies leading to untimely death.

Despite biological advantages that typically result in lower female mortality rates at each life stage, many countries, particularly developing ones like India, face a significant "missing women" issue due to gender inequality. Gender inequality can be found everywhere in India and in forms such as:

- Mortality Inequality: Primarily due to inadequate nutrition and healthcare.

- Basic Facilities Inequality: Many girls are not enrolled in school due to discrimination, which results in an inequal literacy rate and hence no employment.

- Special Opportunity Inequalities: Certain professional roles are reserved for men, based on assumptions about physical and mental efficiency.

- Professional Inequality:

- Employment and promotion disparities.

- Lower wages for women in rural areas despite equal skill levels

- Exclusivity of some jobs for men.

- Ownership Inequality: In India many people still pass on their property to male child.

- Household Inequalities: Women are still forced to work in domestic households while male goes to earn bread.

1) Gender Disparity in Education–A Crucial fueling Missing Women Problem

Because of the above inequalities and discriminations mentioned, many girls and women are unable to complete their education. More than half of the adult illiterates (63%) are women and nearly 2/5th girls enrolled in primary schools are drop-outs before grade 5.

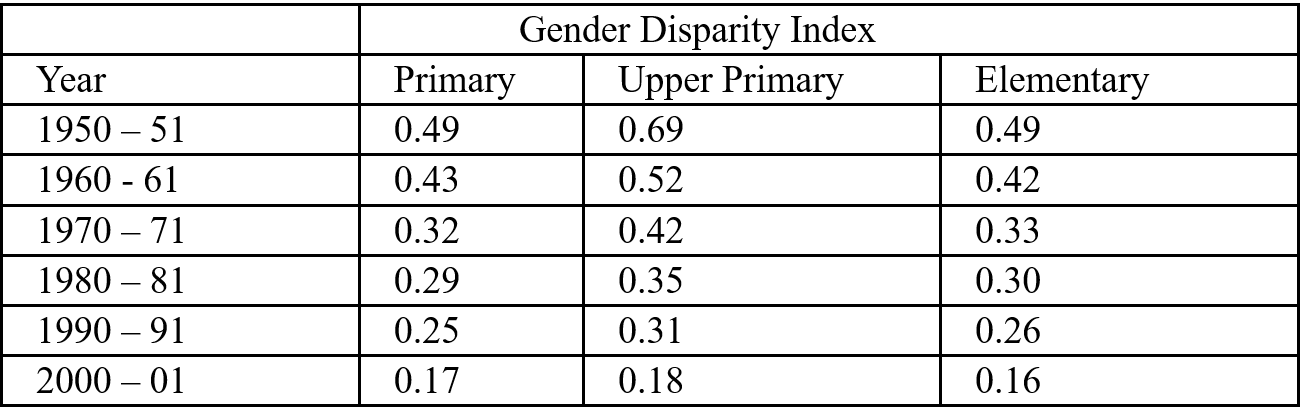

Table 4: Number of Girls per hundred Boys enrolled in school.

Source: Selected educational statistics 2004–05. Ministry of HRD, Department of Education

Source: Selected educational statistics 2004–05. Ministry of HRD, Department of Education

The graph represents the number of girls enrolled in Primary, Upper primary and Secondary schools from the years 1950 to 2005. The data indicates that girls are dropping from the school education from early age in their life and this trend has been analysed till the year 2005.

Reasons for the reduction in numbers of girls enrolled in school in India from 1950s to the current time:

a) Child Marriage

Child marriage significantly hampers girls' access to education in India. In 2016, India recorded the highest number of child brides worldwide, totalling 223 million, with 102 million married before the age of 15. This stands in sharp contrast to the fact that only 4% of Indian males were married by the age of 18. Due to poverty and patriarchy traditions, families prioritize child marriage over education.

b) Inadequate menstrual hygiene

Girls frequently miss school due to menstrual hygiene challenges. This issue stems from poverty and limited access to necessary supplies. Moreover, many girls lack understanding about their menstrual cycle, hygiene practices, and the reasons behind their monthly periods. In India, more than 23 million girls drop out annually due to inadequate access to menstrual products and lack of hygiene education.

c) Child labour

The issue of inadequate education for girls is closely linked to child labour practices, which deprive them of opportunities for success and hinder their emotional, social, and physical development. India faces a significant challenge, with reports indicating around 10.1 million child labourers in the country. While boys are often engaged in skilled vocations outside the home, girls frequently perform domestic labour, which is often overlooked as work despite involving long hours and low wages. Many girls are tasked with caring for younger siblings while their parents work, as families feel compelled to rely on their daughters to make ends meet.

d) Lack of nearby secondary schools

This longstanding issue persists in certain regions of India, were children, particularly girls, encounter obstacles in accessing secondary education due to long distances to schools. This geographical barrier serves as a deterrent to the education of girls in these areas.

Government Initiatives to reduce the above problems and gaps in those policies due to which the situation of gender biasness persists:

The child marriage act 2006 was established in November 2007 in India and forbids child marriages and protects the victims of child marriage. The act failed because the act specifies to protect only those whose marriage is resulting from the force/threat/fraud/kidnapping. Days for Girls is an NGO collaborating with the Indian government to distribute reusable menstrual kits to girls across the country. However, their reach is limited in rural areas due to prevailing stigma surrounding menstruation in India. Despite their efforts, the organization's active presence remains minimal in these regions. Child Labour act 1986 prohibits the employment of children below the age of 14 years in 18 different occupations. It also regulates the conditions of work of children. In 2006, the government of Bihar, an Indian state, initiated a groundbreaking program to enhance school accessibility and narrow the gender gap in secondary education enrolment. The program offered bicycles to girls who pursued secondary schooling to facilitate their attendance.

C. Gender Parity Index

Gender Parity Index (GPI) is an index to assess gender equality in education. GPI measures the ratio of girls’ General Enrolment Ratio (GER) to boys at a given level. When the GPI ratio =1, that shows that the access and opportunities are equal for both girls and boys. Over the years, the gender gap has been narrowing.

Gender Disparity Index = 1 – Gender Parity Index.

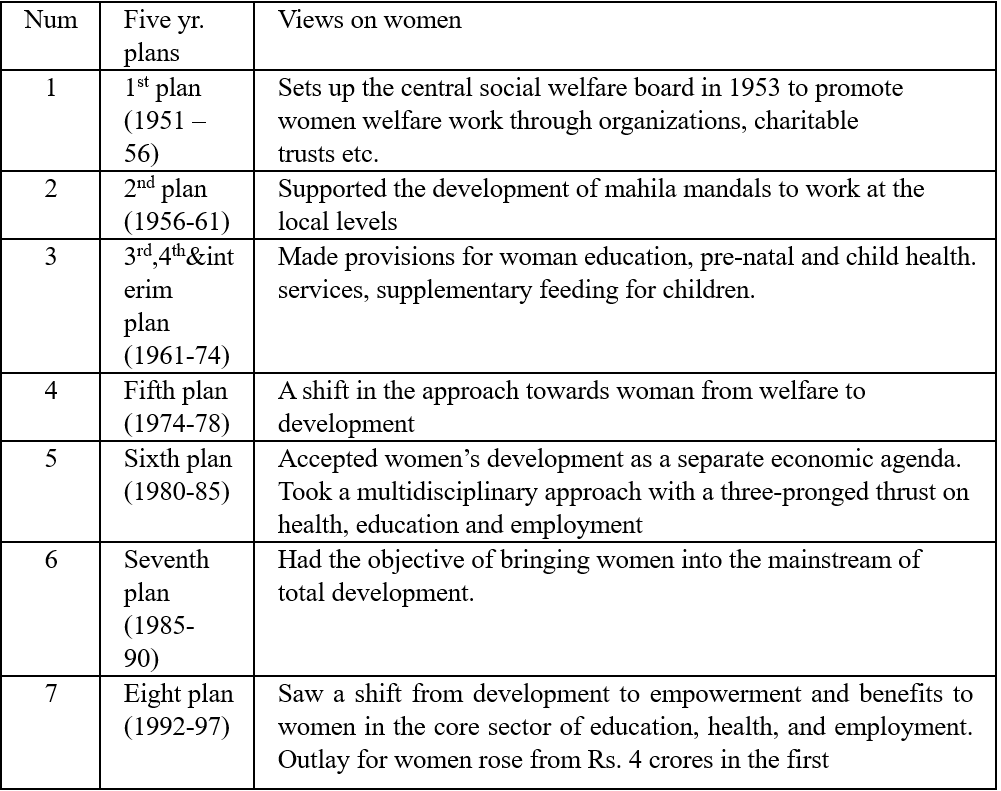

Table 5: Gender disparity index

Source: Based on selected educational statistics, Department of Education, Ministry of HRD

Source: Based on selected educational statistics, Department of Education, Ministry of HRD

The above table provides the data to conclude that women are net getting enough opportunities to education. The data for various years signifies that the GPI is not close to one in all the classes i.e. Elementary, Upper Primary and Primary. These can be because girls are not allowed to study due to household chores or child marriages.

D. Steps Taken by Government of India to solve Missing Women Problem

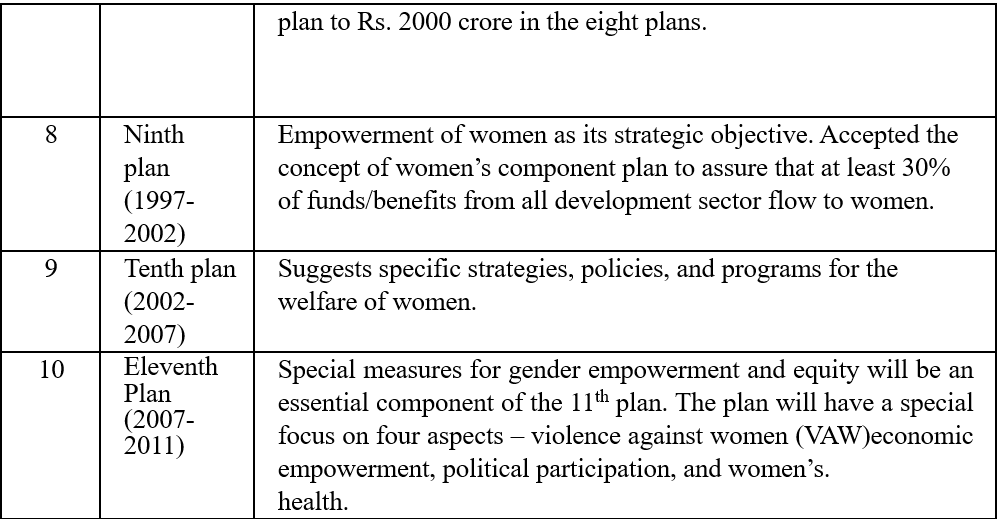

The following table provides the policies and provisions taken in different five years plans.

Table 6: Views of different five-year plans on empowerment of women

Source: ?Women Empowerment Dimensions and directions social welfare, March 2009

Source: ?Women Empowerment Dimensions and directions social welfare, March 2009

VI. GOVERNMENT INITIATIVES

Following is some of the government initiatives to protect women in the gig flatform from exploitations:

Welfare provisions:

- The Building and Other Construction Workers (Regulation of Employment and Conditions of Service) Act, 1996: The act provides measures to increase women construction workers by providing first aid facilities to women along with clean amenities. The above practices provide a safer and comfortable working environment along with employment opportunities.

- The Factories Act, 1948 (Chapter V): This act focuses on women working in factories and the company or owner should keep necessary stuff for them such as canteens, separate restrooms and first aid boxes along with creche for babysitting. The above measures can lead to empowerment in women.

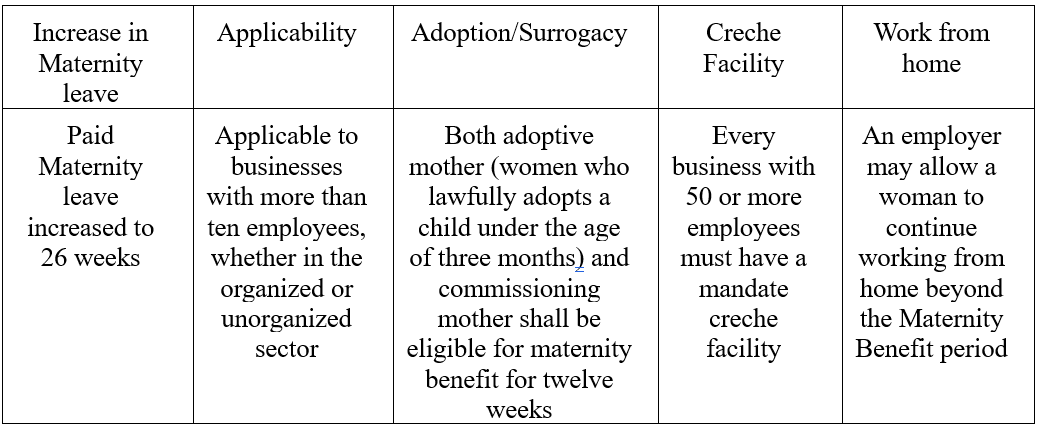

- The Maternity Benefit Act, 1961: The act aims to provide maternity benefits to women employees, the act mandates the employers with over 50 employees to establish women friendly working conditions. The act, in 2017, was amended to extent maternity leave to 26 weeks which earlier was 12 weeks. The act supports parental leave for new parents.

Figure 4: Benefit from the government to women worker

Source: Adapted from Ministry of labour and employment

Source: Adapted from Ministry of labour and employment

- The Maternity Benefit Act, 1961: The act is vital for women workers who are pregnant or has recently given birth, the act supports the idea of giving breaks to the above mentioned for better nourishment along with providing balance work life. The act protects the rights of women and enable them to take maternity leave while also providing access to medical care on job.

- The Sexual Harassment of Women at Workplace (Prevention, Prohibition, and Redressal) Act, 2013: The act is crucial, especially in India, to prevent any mis happenings with women in the workplace. The act ensures a safe working place for them. The act is strictly against any harassment cases, this helps encourage the women to work and increases their participation. The act has laid guidelines as to how to seek redressal against any cases. The act helps in empowerment of women.

- The Payment of Wages Act, 1936: This act ensures timing and mode of wage payments, especially for women. This protects the right of workers and assist them to get fair remuneration. Equal Remuneration Act, 1976: The act focuses on providing fair wages to all the workers.

VII. POLICY RECOMMENDATIONS

A. Reduce the Gaps in Existing Policies

- The child marriage act only focuses on marriages resulting from force/threat or kidnapping, whereas to make this policy more successful it should be extended to marriages under a certain age range punishable.

- The government should host seminars in rural villages about menstruation and support various NGOs working for the same. The government shall also infuse capital for better reach of these NGOs.

- The child labour act 1986 should clearly define what a hazardous work is and government along with local agencies shall keep a regular check on the factories.

- The state government should keep a check on the condition of bicycles and the roads.

- Joint programmes should be made for construction of secondary schools.

B. Broaden Access to Education and Training

The government should ensure free training programs, such as online courses and certification programs, to women in untaped areas, to get a wider reach and encourage women to work. This way women can acquire the required skills and survive in the gig economy.

C. Establish Flexible Scheduling Policies

A more flexible time schedules should be supported for women with childcare duties, this will help them better manage the work and complete both the duties fruitfully. This flexibility is crucial for enabling more women to participate effectively in the gig economy.

D. Handle Discrimination and Bias

The companies should adopt policies that protect women from discrimination in the workplace. This discrimination should be prevented from the lowest level such as hiring to the highest level such as promotion. This inequality has been observed in conventional employment along with the gig economy. Ensuring fair treatment and equal opportunities for women is essential for fostering a more inclusive gig economy.

E. Boost Transparency and Pay Equity

In the gig economy, women are often paid less than men for the same work. Promoting transparency and fairness in pay practices is essential to ensure women receive appropriate compensation for their efforts. Implementing clear rates and payment systems can help address pay disparities and promote equity.

Conclusion

The study was done to find the significant gender gaps and obstacles encountered by women in the gig economy. The overall objective was to achieve a good understanding of the gig economy and what are the opportunities and challenges in that. The research adapts qualitative data along with statistical tools and it was found out that women in the gig platform faces numerous challenges such as unequal pay, gender discrimination, lack of security and benefits. The result of the Chi-Square showcases that women are entitled to a much lower pay as compared to man. The above-mentioned situation arises because of many reasons such as societal behaviour – the idea that men are superior- and the backward thinking in many regions. To address these adverse situations government came up with various policies. These include protection of wages, providing welfare schemes etc. These include gender sensitivity and accessibility awareness programs, collaborations with non-governmental organizations and civil society organizations to promote women\'s legal, economic, and social rights, skill development and asset acquisition programs, the establishment of peer and support groups for mentorship and other forms of assistance, and connections with women in the gig economy. Furthermore, the research delves into the missing women concept in India. The study reveals that missing women phenomenon has been increasing in our country in high developed states such as Punjab, Haryana, Delhi and Chandigarh. Moreover, states with high literacy rates such as Maharashtra and Gujarat are seemingly behind lower literacy states like Odisha and Assam in maintaining their gender ratios. Additionally, rural areas in India, which lag urban areas in education and development, tend to have better sex ratios than urban areas. The findings suggest that economic development and education alone are not enough to eradicate the missing women problem. A closer examination of social, cultural, and economic structures and opportunities is necessary to identify the root causes and ways to confront gender-based discrimination in various forms. The study emphasizes the need to change attitudes regarding son preference, which fuel anti-female bias, and to enforce gender equality legislation effectively. India needs to level up its thinking pattern in many areas to reduce numbers of missing women, ultimately to reach the category of more developed nation every gender needs equal respect and opportunities.

References

[1] Census report 2011 - page 32-33 - https://censusindia.gov.in/nada/index.php/catalog/42610/download/46272/Census%20of%20India%202011-Child%20Sex%20Ratio.pdf [2] Churchill, B., & Craig, L. (2019). Gender in the gig economy: Men and women using digital platforms to secure work in Australia. Journal of Sociology, 55(4), 741–761. [3] Cody Cook, Rebecca Diamond, Jonathan V Hall, John A List, Paul Oyer, The Gender Earnings Gap in the Gig Economy: Evidence from over a Million Rideshare Drivers, The Review of Economic Studies, Volume 88, Issue 5, October 2021, Pages 2210–2238 [4] Farrell, Diana, Fiona Greig, and Amar Hamoudi. 2018. \"The Online Platform Economy in 2018: Drivers, Workers, Sellers and Lessors.\" JPMorgan Chase Institute. [5] Ghosh, Anweshaa and Ramachandran, Risha and Zaidi, Mubashira, Women Workers in the Gig Economy in India: An Exploratory Study (May 1, 2021). [6] Ghosh, Arunabha/Raha, Shuva (2020). Jobs, growth and sustainability: a new social contract for India\'s recovery. New Delhi, India: Council on Energy, Environment and Water (CEEW). [7] Katz, L. F., & Krueger, A. B. (2019). The Rise and Nature of Alternative Work Arrangements in the United States, 1995–2015. ILR Review, 72(2), 382-416. [8] Ministry of labour and employment – page 6 - https://labour.gov.in/sites/default/files/012524_booklet_ministry_of_labour_employement_revised2.pdf [9] Petriglieri, G., Ashford, S. J., & Wrzesniewski, A. (2019). Agony and Ecstasy in the Gig Economy: Cultivating Holding Environments for Precarious and Personalized Work Identities. Administrative Science Quarterly, 64(1), 124-170. [10] Renan Barzilay, Arianne & Ben-David, Anat. (2017). Platform Inequality: Gender in the Gig-Economy. Seton Hall Law Review. 47. 393 - 431. 10.2139/ssrn.2995906. [11] World Economic Forum, 2022 - https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2022/08/gender-pay-gap-gig-economy/ [12] Zippere, Ben et al. National survey of gig workers paints a picture of poor working conditions, low pay. Translated by Alejandra S. Ortiz García. The economic quarter [online]. 2022, vol.89, n.356, pp. 1199-1214. Epub 30-Jan-2023. ISSN 2448-718X.

Copyright

Copyright © 2024 Tarun Bansal, Dr. Swarita De . This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Download Paper

Paper Id : IJRASET64178

Publish Date : 2024-09-07

ISSN : 2321-9653

Publisher Name : IJRASET

DOI Link : Click Here

Submit Paper Online

Submit Paper Online