Ijraset Journal For Research in Applied Science and Engineering Technology

- Home / Ijraset

- On This Page

- Abstract

- Introduction

- Conclusion

- References

- Copyright

Exploring Perfectionism and Coping Strategies: A Qualitative Study among Injured Athletes

Authors: Varsheni. K, Megha D Prasad

DOI Link: https://doi.org/10.22214/ijraset.2024.60008

Certificate: View Certificate

Abstract

This qualitative study explores the experiences of injured athletes in relation to perfectionism and coping strategies during the process of injury and recovery. Drawing upon a phenomenological approach, semi-structured interviews were conducted with a purposive sample of eight injured athletes from various sports background to capture their lived experiences and subjective perspectives. Thematic analysis of the interview data revealed rich insights into the interplay between perfectionism and coping strategies among injured athletes. Results highlighted the pervasive influence of perfectionistic tendencies on athletes\' self-evaluation, goal setting, and emotional responses to injury. Coping strategies ranged from adaptive approaches, such as seeking social support to maladaptive responses, including avoidance and self-criticism. The psychological aspects of the athlete\'s journey are better understood as a result of this study, which also helps with the creation of comprehensive support networks that encourage resilience and overall wellbeing in wounded athletes

Introduction

I. INTRODUCTION

Participation in professional sports is an intense and challenging endeavor characterized by strenuous training, high levels of motivation and stress accompanied by tough competition (Robert Masten et. al, 2014). Extreme levels of effort and the pursuit to attain perfection in performance may also lead to pushing the physical body into extreme stress, thus, leading to injury of different kinds among various athletes. It is essential to understand the different kinds of responses that athletes show during the injured phase, as their reactions to injuries vary greatly, displaying a broad spectrum of behavioral, emotional, and cognitive reactions. The term sports injury can be defined as damage to one’s body sustained during or following participation in sports, these injuries can affect various parts of the body like bones, muscles, ligaments, joints and tendons and can range by their intensity from minor issues like sprain or bruises to major issues like fracture, dislocation and ligament tears (Masten, R. et al, 2014). From the physical perspective sports injury can be defined as a functional consequence of participating sporting activities and it involves assessing how injuries affect the athlete’s performance in specific physical tasks and activities and also depends on the setting in which the injury is observed and reported (Masten, R. et al, 2014). From psychosocial perspective, sports injuries lead to emotional responses of athletes depending on the severity of the injury ((Toomas et. al, 2014). The injured athlete may go through certain feelings that are comparable to those included in the grieving process. The athlete is likely to react initially with shock, denial, and an unduly hopeful notion that the injury is less serious than it appears, especially in the case of a catastrophic injury (Grove, B. ,1993).

For most athletes, their athletic ability is a crucial aspect of their identity and their achievements; hence, an injury may jeopardize their sense of self, leading to irrational behavior responses like overtraining, ignoring pain and discomfort, having unrealistic performance standards, and fear of failure. Furthermore, some theoretical models explain perfectionistic concerns to be the predictor for athletic burnout and injuries, according to (Williams and Andersen, 1998) proposes two ways in which athletes may be more vulnerable to injury as a result of perfectionistic worries. The stress-injury concept is the foundation of the first pathway (Williams and Andersen, 1998). This model states that stress exposure increases the chance of injury and that personality traits (i.e., individual characteristics that make athletes more sensitive to stress) moderate this association. It is often shown that injuries due to stress can have negative psychological impact like developing negative emotions of anger, low self-esteem and depression. Thus, the consequences of an injury will partly depend on how athletes cope with it.

Coping is defined as continuously modifying one's behavior in an effort to meet particular internal and external expectations that are deemed to be too demanding or resource-intensive for an individual.(S Folkman et al, 1986) The coping strategies adopted by athlete when faced with injury is subjective based on a number of variables, including age, competitiveness level, degree of injury, length of recovery period, and history of previous injuries, will be crucial in determining whether or not an individual's coping mechanisms are adaptive such as goal setting and structured rehabilitation plans, while others may struggle with maladaptive coping, including increased anxiety, self-criticism, or engaging in risky behaviors to hasten recovery (Johnson. U. ,2007).

The most prevalent models of coping strategies brought out the broad coping dimensions determined by how similar coping strategies' functions are (Carver & Connor-Smith, 2010). Problem-focused coping, emotion-focused coping, and avoidance coping are the major coping components that are most frequently examined in sport research (Nicholls & Thelwell, 2010)

II. REVIEW OF LITERATURE

Sport medicine is one of the newest disciplines within the medical field to tackle health issues associated to athletes. While the focus has typically been on an athlete's physical health, many medical professionals, coaches, trainers, and physical educators are now aware that psychological factors may play a significant role in an athlete's experience during the injury and recovery phase (Rose, j., et. al, 1993). Johnston, L. H. and Carroll, D (1998) in their study found the initial reaction of athletes towards injuries Participants initially experienced shock and disbelief upon sustaining their injuries. While some immediately recognized the severity of their situation, others who had previously encountered similar accidents did not. Following this initial shock, each individual evaluated the extent of their injuries. During the middle stages of their rehabilitation programs, some athletes displayed apathy and inconsistent adherence to their prescribed exercises. This behavior may stem from impatience and a strong desire to resume sports activities or from a lack of motivation to complete rehabilitation tasks.

Kamphoff et al, (2013) studied the psychological challenges experienced by injured athletes in a phase- like approach that connected particular psychosocial difficulties. More precisely, athletes frequently feel negative cognitive appraisals and anxiety throughout the reaction-to-injury period. Van Wilgen, C. P., and Verhagen, E. A. L. M. (2012), studied the increasing propensity among athletes to overlook bodily indicators of exhaustion or pain in their quest for excellence that might lead to ignoring pain or mild injuries, delaying treatment of the problem and increasing the risk of more serious overuse injuries which is increasingly prevalent. Research has provided compelling evidence that perfectionism and athlete exhaustion are related. According to a study on perfectionism, (Madigan et al. 2017), found a positive correlation with the likelihood of an accident. Perfectionistic striving did not significantly correlate with the likelihood of injuries, even though only perfectionistic concerns emerged as a strong positive predictor. As a result, athletes who worry more about perfection would be more likely to get hurt than athletes who worry less about perfection. (Sellars, et al 2016), in their findings implied that detrimental perfectionists are prone to judging failures with excessive harshness, when compared to training, their perfectionist tendencies were more pronounced during competition. Damien Clement et al. (2015) studied that Some athletes after being aware of how serious their injuries were helped them to have a more optimistic attitude on the matter, while others voiced pessimism or saw it as a problem they had to overcome. Kaul, N. (2017) in their study, analyzed coping strategies and support systems that were employed by injured athletes, it was found that in addition to causing pain, the injury and recovery period made the participants resentful of friends and other individuals who were successful in life while they desperately tried to heal and resume their running and walking. Studies on sports related injuries by (Malcolm, D., and Pullen, E. 2020) display all of the possible "coping," "strategy," and "style" reactions of participants and This was especially clear when it came to the main way that people "coping" with sports related injury try to play despite pain and with injuries. Many respondents expressed their perception that it was "unfair," that they had to experience such injuries. Therefore, SRI may result in a fundamental reconstruction of one's identity and course for the future. Therefore, understanding on how perfectionistic striving manifests in the coping behaviors of injured athletes is essential to developing targeted interventions that address their unique psychological needs.

Our research aims to examine the types of coping strategies within the framework of perfectionistic pursuits that will enhance our knowledge of the variables impacting the wellbeing of athletes while they recover. Since, fewer studies have looked closely at the long-term effects of maladaptive coping mechanisms in injured athletes who exhibit perfectionistic tendencies. The prime scope of our research sheds light on the possible long-term repercussions on an athlete's mental health, performance, and general well-being which will help develop support networks and preventative measures.

III. METHODOLOGY

A. Aim

The aim of this study is to explore the impact of perfectionism on the athletes' experiences navigating the obstacles of injury and rehabilitation.

B. Objective

- to study the lived experiences of injured athletes with perfectionistic inclination, explore how they view, understand, and cope with the difficulties posed due to their injuries

- to study the coping strategies used by injured athletes with perfectionistic tendencies, looking at both maladaptive and adaptive mechanisms during the injury and rehabilitation process.

- To study the function of social support in the context of perfectionism and coping among injured athletes, including family, coaches, and teammates.

C. Research design

Eight athletes from various sports suffering from injuries were interviewed as a part of a qualitative study by employing a descriptive phenomenological method to investigate how perfectionism and coping mechanisms relate to the lived experiences of injured athletes. To provide an in-depth analysis of people's subjective experiences, perceptions, and interpretations of those experiences is made possible by phenomenological study.

D. Inclusion Criteria

This study will include athletes aged 20 and above, both female and male, who have experienced injuries related to sports, encompassing those who have fully recovered, are currently undergoing rehabilitation, and are engaged in contact or team sports.

E. Exclusion Criteria

This study will exclude individuals who have sustained injuries not related to sports, including non-athletes, as well as athletes below the age of 20, specifically targeting those not involved in contact or team sports.

F. Procedure of the Study

Semi structured interview with questions emphasizing on the experiences faced by injured athletes, the perfectionistic striving, standards, realities, coping strategies and the kind of social support they received. The interview guide will be validated by 3 qualitative researchers, following which the interview will proceed. Thematic coding from each response given by the participants and discussions including all the themes and their meaning. Table 1 shows the detailed characteristics of the participants

Table 1 Socio Demographic details of the participants

|

Sex |

Age |

Sport |

Competitive level |

Injury |

severity |

|

Male |

24 |

Football |

State level |

Anterior cruciate ligament injury & Knee injury |

10 months |

|

Male |

24 |

Football |

State level |

ACL Injury |

6 months |

|

Male |

24 |

Football |

State level |

ACL Injury |

8 months |

|

Male |

26 |

Football |

State level |

ACL & MCL Injury |

10 months |

|

Male |

22 |

Football |

club/regional |

ACL Injury |

12 months |

|

Male |

26 |

Basketball |

University/ clubs |

ACL& Meniscus Tear |

10 months |

|

Male |

23 |

Basketball |

University |

ACL Injury |

6 months |

|

Male |

23 |

Football |

State level |

ACL injury |

|

IV. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

TABLE 2: Basic Themes and Organizing themes that emerged from codes

|

Organising Themes |

Basic Themes |

Codes |

|

Perfectionism |

Striving for perfection |

Perfectionist traits and tendencies |

|

Neglect and turmoil |

||

|

High standards |

||

|

Perfectionism and adaptation |

Self-compassion and acceptance |

|

|

Resilience |

Resilient recovery |

Post injury resilience |

|

Resilient effort |

||

|

Athletic identity |

Athletic persistence and identity |

Sense of self |

|

Belonging and community |

||

|

Drive and ambition |

||

|

Coping strategies |

Navigating psychological turmoil |

Emotional turbulence |

|

Self-reflection and insight |

||

|

Navigating physical limitations |

Social support and inclusion |

|

|

Physical health management. |

||

|

Integrated support network |

Unified support framework |

Encouragement and affirmation |

|

Social emotional support |

||

|

Digital support ecosystem |

Information and resources |

|

|

Virtual communities |

||

|

Rehabilitation |

Empowered rehabilitation journey |

Multidisciplinary approach |

|

Individualised care plans |

||

|

Positive mindset |

A. Theme 1: Perfectionism among injured athletes

Perfectionistic striving captures the perfectionist ideals and a self-centered pursuit of excellence (Madigan,D. J et. al., 2017). These themes examine the complex views, experiences, and actions of athletes rehabilitating from injuries sustained during sports. Striving for perfection involves getting back to their pre-injury performance, fitness, or ability levels, and acts as an example of their desire for perfection. The analysis showed that participants felt “angry” “sad and depressed”. They expressed their strong desire to meet expectations of themselves, teammates and coaches, participant 4. “.... The expectation that I had when I was playing and when I got injured changed, because obviously, the team wants you back; they want you to recover fast." And participant 1 expressed that “.... Yeah, I pushed myself to keep setting better targets, never really settling for. It was never enough.” which interprets that these participants' statements suggest a strong drive to achieve excellence and meet high standards, both before and after injury.

It explores the neglected aspects of injured athletes' experiences, including feelings of frustration, anger, sadness, or anxiety stemming from the inability to participate in sport and achieve desired performance levels. Participant 6 expressed that

“...during my injury days, I was always like, why did this happen to me? Why can't I just get back into the field? So later on, I realized that there was no patience in me.” Which is interpreted as the participant expressing his feelings of neglect, questioning why the injury happened to him. Perfectionist-inclined injured athletes could have inflated expectations for their recovery, results, or return to competition, which would put more strain and stress on them. Another participant voices his opinion on the importance of basic functionality through acceptance

“...You're at a stage where you don't really know if you can play again, you don't really know if you can walk again. So, getting back and playing is what I wanted but you have just gotten up and walking normally being able to travel certain do the most minimalistic things which a normal person could do” (p4)

The significance of self-acceptance and self-compassion in the context of injury recovery is emphasized in the second sentence. The athlete talks about the worry and anxiety that come with not knowing if they will be able to use their physical ability again.

This change in emphasis indicates a readiness to put one's own needs and well-being ahead of accomplishing other people's expectations, as well as an acceptance of one's own constraints.

B. Theme 2: Resilience

The process through which people show resilience in the face of harm or adversity and manage the psychological, social, and physical effects of their experiences is known as resilient recovery. It has to do with a person's ability to tolerate, adjust to, and get past obstacles that come up during the healing process, supporting development and wellbeing in the face of hardship. The psychological and emotional resilience that people exhibit in the wake of an injury is the main emphasis of this theme. Post-injury resilience refers to a person's capacity to manage the psychological, social, and physical effects of an injury, adjust to changing circumstances, and keep a good attitude in the face of setbacks.

Participants expressed resilience in various contexts like

“...So, when I started understanding my body... the whole focus shifted to just understanding my body than going back to the field and playing”. (p2)

"So, I just broke it down... I was more sincere and committed towards fulfilling what my goal is right now."(p1)

"Gradually, my confidence is coming back” (p3)

Describes breaking down goals into manageable steps and committing to the present task, showcasing resilience in adapting goals during recovery. And despite facing injuries, the individual acknowledges their recovery and remains determined to overcome limitations. They shifted their attention to comprehending their bodies rather than diving back into the game. This change shows tenacity in overcoming obstacles and realizing the value of self-awareness and injury prevention. The athlete displays resilience by adopting a holistic approach to their rehabilitation path and placing a high value on understanding their body.

Resilient effort refers to the ability to persistently and effectively work towards goals, overcome obstacles, and bounce back from setbacks, particularly in the face of adversity or challenges. It involves maintaining determination, adaptability, and perseverance despite encountering difficulties or setbacks along the way. Participants expressed their attitute towards enduring difficulties by saying that:

“So understanding your injury is very important. And dealing with is also very important."(p5)

"So having that maturity and working on that injury, doing physiotherapy and exercise is getting getting recurred day by day is important." (p6) These above statements given by participants indicate resilient effort, as the individuals emphasizes the importance of maturity and dedication in managing injuries. Despite facing setbacks, they recognize the necessity of adhering to rehabilitation routines and remaining committed to the recovery process, showcasing resilience in their determination to overcome challenges and achieve gradual improvement.

C. Theme 3: Sports Persona

Athletes' sense of self is frequently closely linked to their athletic success, especially those with perfectionistic impulses. Athletes who suffer injuries may find their sense of self severely disrupted, particularly if those ailments prevent them from giving their best effort. Beyond their sporting successes, they could struggle with feelings of inadequacy, loss, and confusion about who they are "I used to aim for perfection... constant belief about myself that I'm not good enough." This remark demonstrates reflection on prior actions and convictions and demonstrates knowledge of one's own mental processes and sense of self. (p8)

"I just accepted that... My leg is not going to be as good as it ever was. I accepted that my leg is weak currently.". (p5)

The statement shows a change in perspective from aiming for excellence to accepting the limits placed on by the injury. An increasing sense of self-awareness and adaptability is evident when the person accepts the reality of their circumstances and starts to balance their high ideals with the physical limitations they must work within. The underlying sense of belonging to the athletic group is apparent, even in spite of the need for isolation. The choice to make space implies a short-term approach to concentrate on individual healing as opposed to a total detachment from society.

“I took a long break from basketball. I wasn't seen anywhere on court for a long time." (p6)

This statement highlights the athlete's decision to take a break from participating in basketball, indicating a temporary withdrawal from the sports community. This break likely involved refraining from attending games, practices, or other team activities, which can impact their sense of belonging within the sports community. Injuries might pose serious obstacles to this motivation and ambition. Athletes who suffer injuries that keep them out of the game must deal with physical constraints that make it difficult for them to prepare, compete, and reach their objectives. For athletes who are used to pushing themselves to the edge, this break in their routine can be discouraging and upsetting. They could feel dejected, frustrated, or even afraid of losing their competitive advantage or lagging behind their colleagues. For athletes who place a great deal of value on their athletic accomplishments, being unable to participate in their sport as frequently or at the same intensity as previously might cause them to experience a sense of loss and identity crisis.

“But I was scared and I was eagerly bonded to play because I was at my peak and my team wanted me badly.” (p5) Despite feeling scared, the athlete expresses a strong desire to play and contribute to their team, indicating a high level of ambition and commitment to their sport.

“So obviously, being in a prime being a good model to others and depending on you, if team is there, so obviously you have to perform good you have to be your best and you have to keep improving game by game." (p3) interpreting that they athlete sets high standards for themselves, emphasizing the importance of performing well and constantly improving, demonstrating ambition and a drive for excellence.

D. Theme 4: Coping Strategies

The act of controlling and overcoming severe emotional difficulties and mental anguish. This idea frequently comes up when people are going through difficult times, like traumatic experiences, long-term stress, or big life changes. Experiencing turbulent emotions due to their injuries, athletes who have a tendency toward perfection frequently reflect on their experiences and learn important lessons about themselves and their connection to their sport. Individuals could contemplate their objectives, driving forces, and the fundamental causes of their incessant need for perfection. They can better grasp their own psychology, including how they react to obstacles and setbacks through this self-reflection. They might gain more self-awareness and understanding of their advantages, disadvantages, and opportunities for personal development as a result of this process. Participants expressed their feelings about their actions before and after injury and how self-reflection help them a lot with coping with the injuries.

"So recently a few months back I discovered I mean while working on myself I discovered that it was it was because of lack of self-esteem, the lack of self-love."(P2)

"I can control how I treat my body and that is what I'm doing now. And I'm in no pressure right now. Because I have more self-faith now."(P5)

“So, when you realize that, that know that if you push yourself in this injury will lead you nowhere but it will get bad and when you realize it and get matured” (P6)

These statements show the path of their self-discovery and growth in understanding their own psychological dynamics. It also reflects the athlete's introspection and realization regarding the underlying elements driving their perfectionistic impulses. And a greater degree of self-understanding and empowerment obtained through the injury experience. It also shows the athlete's recognition that they can impact their own well-being through self-care and their newly discovered sense of self-assurance. The athletes expressed their gratitude towards the different kind of social support they received to navigate the physical limitation

“So people around me helped me a lot.” (p4)

“My friends who helped me when I got injured, they took me to the hospital. They were helped me inquire about my health record for injury and help me move on and accept the situation” (p7)

This quote emphasizes the importance of friends in offering both practical and emotional support during the difficult times. In order to preserve general functionality and well-being, people with physical limitations must manage their physical health. This covers treatments such as medical interventions, rehabilitation plans, adaptive workouts, and assistive technology made to fit the unique requirements and circumstances of each person. Maintaining or enhancing strength, flexibility, endurance, and mobility are all important aspects of physical health care. Other goals include controlling pain, averting problems, and advancing general health. This could entail collaborating with medical specialists like doctors, physical therapists, occupational therapists, and rehabilitation specialists to create individualized treatment plans and methods for symptom management and optimizing independence. The participants tried to maximize their functional abilities and quality of life even in the face of physical constraints by making physical health management a priority.

" So, when I saw that and I checked with my body, there were limitations when it comes to flexibility and strength. So, I had to work on that limitation to perfect that mechanism. So, I used to, you know, try different positions in which those parts of the body were, you know, active." (p1)

This statement highlights the athlete's proactive approach to managing their physical health during the recovery process. The athlete acknowledges limitations in flexibility and strength and takes steps to address them by trying different positions to activate specific parts of their body. This demonstrates a hands-on approach to understanding and improving their physical condition, indicating a focus on managing their physical health effectively.

E. Theme 5: Integrated Support Networ

Athletes who sustain injuries frequently deal with serious psychological and physical issues, such as self-doubt, failure anxiety, and dissatisfaction with setbacks. Support and validation are essential in assisting athletes in overcoming these obstacles and keeping a positive outlook while they heal. Giving injured athletes verbal or nonverbal support is a form of encouragement that helps them feel better and stay motivated. Coaches, teammates, medical experts, and loved ones may say encouraging things to support the athlete and recognize their hard work, growth, and fortitude. They explained the kind of encouragement and affirmation they received that developed a lot of hope and motivation during the recovery phase

“There are friends and coaches who share their experience, because it's not only me who is getting injured, there are those who is suffering and have faced these injuries.” (p8)

“So, I have I have friends and coaches who suggested their things to cope up with my injury.” (P1)

“My coach was crucial help. He gave me a sense of hope that, like, you know, everything's going to be fine.” (p6)

“But a few of my friends just like I said, Really, you know sat with me and try to understand what I was actually trying to do. And yeah, other players, other people were helpful. Yeah, they're trying to help me with football which I didn't require. So, I'm grateful for them.” (p3)

The athlete's perspective and emotions are validated when friends and coaches discuss their own experiences with comparable ailments. It demonstrates that they are not alone in their difficulties and that others have faced and overcome comparable difficulties. For an injured athlete, this confirmation can be comforting and reassuring because it shows them that their sensations are real and shared by others. The larger web of connections and interactions that foster a feeling of solidarity, friendship, and belonging is referred to as social support. These people

include teammates, other athletes, coaches, medical professionals, and internet groups where athletes may exchange stories, look for guidance, and promote one another's support. These participants expressed their gratitude for receiving emotional and social support during their sufferings.

"It was just my mom, dad and grandparents because we live where neighbors are very close. So they were the only constant support. So, give me that's a very crucial role to have your parents with helping with your diet and with your rehab exercises making sure you do it because you do lose motivation you do lose the constant effort to put in because you lose hope sometimes but they really made a change" (p1)

highlights how important it is for the athlete's family especially their parents and grandparents to be there for them constantly while they heal from their injuries. They provide practical help with things like nutrition management and rehabilitation activities, as well as emotional support and encouragement. The athlete admits that throughout the difficult recovery phase, it is simple to lose hope and drive, but that having their family's continuous support greatly helps them to remain dedicated to their rehabilitation process.

“My coach played an important role, told me to take my time and come back. He himself has seen people, his own family, his own father with this injury and recovering from it. So, I think his experience really helped when it came to dealing with my injury as for my teammates, the ones who really underscored or at least the ones I've been playing a lot with, they also wanted me to. They also had faith that had made me come back.” (p4)

The support received from the athlete's coach and teammates. The coach plays a vital role by providing guidance and reassurance, drawing from their own experiences with injury and recovery.

The Digital Support Ecosystem refers to the comprehensive network of online resources, platforms, and communities that provide various forms of support, information, and connection to athletes dealing with injuries. This ecosystem plays a crucial role in facilitating coping strategies and aiding the recovery process.

Through digital platforms like websites, forums, and online publications, athletes who are dealing with injuries can access a variety of information and tools about managing their ailments, rehabilitation activities, recovery timetables, and potential therapies. Participants expressed “researching” about their conditions on various online platforms for better understanding of their injuries and learned different coping strategies that fastened their recovery phase.

“.... There is this sort of like a 10-step progression kind of sheet. I think there's a very famous a well cited article available online and there's even this video on YouTube I think, so they have a very specific video which shows like these 10 steps in which athletes recover.” (p6)

The reference to a "10-step progression kind of sheet" implies that athletes may have access to a structured framework to use while they recuperate. This sheet probably describes a sequence of actions or phases that sportsmen can follow to progressively recover from their injuries. The mention of a "well-cited article available online" highlights the availability of knowledge about recovering from injuries even more. It's possible that this article offers thorough justifications, advice, and suggestions for athletes undergoing rehabilitation.

“.... If you're if you're rested for four or five days and then proper like you know, the you know, the rice protocol, right. So Rest, Ice, Compression and Elevation. which i followed very diligently” (p5)

Using the RICE protocol (Rest, Ice, Compression, Elevation) demonstrates how to apply a commonly accepted technique for treating acute injuries. Early on in an injury, this approach helps athletes manage discomfort, swelling, and inflammation.

Virtual communities serve as a valuable source of information and resources related to injury recovery.

F. Theme 6: Empowered Rehabilitation

Athletes who sustain injuries frequently need comprehensive assistance that attends to their mental and emotional health in addition to their bodily wounds. A multidisciplinary approach entails the cooperation of several medical specialists, such as doctors, physiotherapists, sports psychologists, dietitians, and strength trainers. Every member of the interdisciplinary team contributes special knowledge and viewpoints to the athlete's recovery.

“.... People who practically solve injuries who are doctors, physiotherapists, chiropractors and instructors like yoga, Pilates, blah, blah, blah. Because they recover. They work on the body so much they know what muscles need to be developed in order to overcome any imbalances in strength and I started Pilates and yoga along with strengthening which worked absolutely best for me” (p1). The statement highlights the importance of seeking guidance and support from healthcare professionals, such as doctors, physiotherapists, chiropractors, and instructors in disciplines like yoga and Pilates, during the recovery process from injury. Athletes who adopt a positive view can sustain their enthusiasm, focus, and determination throughout their rehabilitation process, even though injuries can be physically and emotionally exhausting. By lowering stress, improving psychological well-being, and encouraging adherence to rehabilitation measures, positive thinking can help speed up healing.

“I started the journey of, you know, just doing it myself. You know, believing in myself that I can do it and then doing it myself. So, I'm doing good now” (p3)

“Be more confident about myself but this injury gave me you know, when I concentrated about just recovering from these injuries. I understood that you know, when I can do so well” (p5)

“I developed the feeling and thought process that I can take on anybody I can take on the world and I will still be able to overcome it, overcome any problem as such, and overcome any kind of mental or physical pain so those are some things which are going to be able to face anything and everything and overcome.” (p6)

“I have a positive outlook towards life because if something has to happen” (p2)

These statements of different participants emphasize how concentrating on getting better after an injury resulted in more confidence. The person developed a greater awareness of their own skills and resilience by focusing their efforts and attention on conquering the obstacles that an injury presented. This shows how persistence and resolve, even in the face of disappointments, may cultivate confidence. the person's resilient mindset and will to get past challenges. The person gained confidence in their capacity to face and overcome any obstacle in their path, even in the face of bodily and emotional suffering. A positive viewpoint on life is exemplified by this mental shift from perceiving challenges as insurmountable obstacles to viewing them as chances for empowerment and growth.

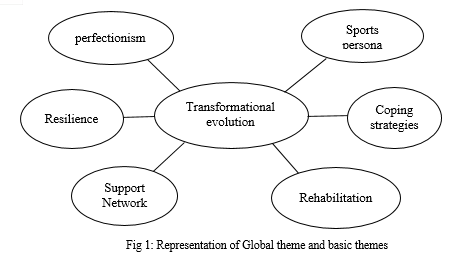

G. Global theme: Transformation Evolution

The study's overarching concept, "Transformational Evolution," resulted from a synthesis of the related topics examined during the investigation. This overarching theme of transformational progress was enriched by the contributions of each theme, which included overcoming psychological and physical constraints, athletic identity, resilient recuperation, unified support, digital support, and striving for perfection. Athletes, who suffered injuries had to overcome difficult challenges that put their physical and mental toughness to the test. Through these difficulties, they underwent a deep metamorphosis and became stronger, more resilient people. Their journey was not just about conquering hardship. Athletes had to reassess their identities as they battled ailments that could have ended their sports careers. Beyond their physical prowess, they unearthed deeper facets of themselves strength, flexibility, and resolve, for example which altered their perception of themselves as athletes and as people going through a metamorphosis. The study's main finding was resilience, which showed how athletes used setbacks as opportunities for personal development. They developed resilience by accepting obstacles and failures, and as a result, they came out of their rehabilitation stronger and more resilient than before. It conveys the essence of people going through a process of self-improvement, adaptability, and resilience. It suggests a dynamic process of growth and transformation in which people overcome challenges, gain knowledge from events, and become stronger and more resilient.

V. LIMITATIONS

- Limited Generalizability: Because most of the participants in the study were football players and there were few female participants, the study's findings may not be as broadly applicable as they could be. This limits the findings' relevance to a larger group of athletes by underrepresenting the experiences and viewpoints of female athletes and players from different sports.

- Gender Disparity: The study's lack of female participants limits our ability to comprehend the ways in which gender-specific elements could impact athletes' transformative progress. It is important to conduct additional research to examine the disparities that female athletes may face from their male counterparts in terms of problems faced and coping mechanisms.

- Sport-related bias: Because football players are overrepresented in the study, there may be a bias related to their experiences and difficulties compared to athletes in other sports. Because of this, the results are not as applicable to individuals with varied athletic histories, and extending the findings to other athletic situations should be done with caution.

VI. FURTHER SUGGESTION

Future research may assist to provide a more thorough knowledge of transformative evolution in both genders. This would make it possible to examine the difficulties, coping mechanisms, and experiences unique to female athletes during their recuperation and personal development processes. Longitudinal research would provide information about the long-term course of athletes' transforming experiences. Through prolonged observation of athletes, researchers can discern how their experiences, coping mechanisms, and perspectives change over time, offering a more refined comprehension of transformational evolution.

VII. ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The author appreciates all those who participated in the study and helped to facilitate the research process.

Conclusion

The journey of an athlete is not only a desire for physical excellence but also a profound inner transformation. This qualitative study illuminates the complex interplay between injured athletes\' coping mechanisms and perfectionism. It was discovered via in-depth interviews and theme analysis that athletes\' perfectionism takes numerous forms, which affects how they react to injuries and develop coping strategies as a result. Our research highlights the complicated and multifaceted character of perfectionism in injured athletes, emphasizing both its advantages and disadvantages. Perfectionism can motivate athletes to pursue greatness, but it can also worsen psychological discomfort and hinder the healing process. Consequently, our research highlights how critical it is to help injured athletes develop resilience and adaptive coping mechanisms, especially in the face of perfectionism.

References

[1] Arvinen-Barrow, M. (Ed.). (2013). The Psychology of Sport Injury and Rehabilitation (1st ed.). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203552407 [2] Bolling, C., Barboza, S. D., Van Mechelen, W., & Pasman, H. R. (2020). Letting the cat out of the bag: athletes, coaches and physiotherapists share their perspectives on injury prevention in elite sports. British journal of sports medicine, 54(14), 871-877. [3] Byrd, M. M. (2011). Perfectionism Hurts: Examining the relationship between perfectionism, anger, anxiety, and sport aggression (Master\'s thesis, Miami University). [4] Damien Clement, Monna Arvinen-Barrow, Tera Fetty; Psychosocial Responses During Different Phases of Sport-Injury Rehabilitation: A Qualitative Study. J Athl Train 1 January 2015; 50 (1): 95–104. doi: https://doi.org/10.4085/1062-6050-49.3.52 [5] Folkman, S., & Lazarus, R. S. (1986). Stress processes and depressive symptomatology. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 95(2), 107–113. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1037/0021-843X.95.2.107 [6] Flett, G. L., & Hewitt, P. L. (2002). Perfectionism and maladjustment: An overview of theoretical, definitional, and treatment issues. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1037/10458-001 [7] Grove, B. (1993). Personality and injury rehabilitation among sport performers. In D. Pargman (Ed.), Psychological Bases of Sport Injuries (pp. 99-120). Fitness Information Technology. [8] Grindstaff, J. S., Wrisberg, C. A., & Ross, J. R. (2010). Collegiate athletes’ experience of the meaning of sport injury: A phenomenological investigation. Perspectives in Public Health, 130(3), 127-135.https://doi.org/10.1177/1757913909360459 [9] Gotwals, J.K., & Spencer-Cavaliere, N. (2014). Intercollegiate perfectionistic athletes’ perspectives on achievement: Contributions to the understanding and assessment of perfectionism in sport. International Journal of Sport Psychology, 45, 271-297. http://dx.doi.org/10.7352/IJSP2014.45.271 [10] Johnson, U. (2007). Coping strategies among long-term injured competitive athletes. A study of 81 men and women in team and individual sports. Scandinavian Journal of Medicine & Science in Sports, 7(6), 367–372. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0838. 1997.tb00169.x [11] Jowett, G. E., Hill, A. P., Forsdyke, D., & Gledhill, A. (2018). Perfectionism and coping with injury in marathon runners: A test of the 2× 2 model of perfectionism. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 37, 26-32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2018.04.003 [12] Johnston, L. H., & Carroll, D. (1998). The Provision of Social Support to Injured Athletes: A Qualitative Analysis. Journal of Sport Rehabilitation, 7(4), 267–284. doi:10.1123/jsr.7.4.267 [13] Kaul, N. (2017). Involuntary retirement due to injury in elite athletes from competitive sport: a qualitative approach. Journal of the Indian Academy of applied psychology, 43(2), 305-315. [14] Malcolm, D., & Pullen, E. (2020). ‘Everything I enjoy doing I just couldn’t do’: biographical disruption for sport-related injury. Health, 24(4), 366-383 [15] Martin, S. (2018). Are perfectionistic and stressed athletes the main victims of the «silent epidemic»? A prospective study of personal and interpersonal risk factors of overuse injuries in sport. [16] Madigan, D. J., Stoeber, J., & Passfield, L. (2017). Perfectionism and training distress in junior athletes: a longitudinal investigation. Journal of sports sciences, 35(5), 470-475. [17] Rose, J., & Jevne, R. F. J. (1993). Psychosocial Processes Associated with Athletic Injuries. The Sport Psychologist, 7(3), 309–328. doi:10.1123/tsp.7.3.309 [18] Smith, A. M., Scott, S. G., & Wiese, D. M. (1990). The Psychological Effects of Sports Injuries. Sports Medicine, 9(6), 352–369. doi:10.2165/00007256-199009060-00004 [19] Sellars, P. A., Evans, L., & Thomas, O. (2016). The effects of perfectionism in elite sport: Experiences of unhealthy perfectionists. The Sport Psychologist, 30(3), 219-230. [20] Salim, J., Wadey, R., & Diss, C. (2016). Examining hardiness, coping and stress-related growth following sport injury. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, 28(2), 154-169. [21] Singh, Karanbir1; Singh, Paramvir2, Incidence of Sports Injury and its relationship with psychological factors: A qualitative review. Saudi Journal of Sports Medicine 21(3): p 75-80, Sep–Dec 2021. | DOI: 10.4103/sjsm.sjsm_25_21 [22] Sagar, S. S. Sagar, SS, & Stoeber, J. (2009). Perfectionism, fear of failure, and affective responses to success and failure: The central role of fear of experiencing shame and embarrassment. Journal of Sport & Exercise Psychology, 31 (5), 602-627. [23] Tranaeus, U., Johnson, U., Engstrom, B., Skillgate, E., & Werner, S. (2014). Psychological antecedents of overuse injuries in Swedish elite floorball players. Athletic Insight, 6(2), 155. [24] Van Wilgen, C. P., & Verhagen, E. A. L. M. (2012). A qualitative study on overuse injuries: the beliefs of athletes and coaches. Journal of Science and medicine in Sport, 15(2), 116-121. [25] Wadey, R., Evans, L., Hanton, S., & Neil, R. (2012). An examination of hardiness throughout the sport-injury process: A qualitative follow-up study. British Journal of Health Psychology, 17(4), 872–893. doi:10.1111/j.2044-8287.2012. 02084.x [26] S. Zhang, C. Zhu, J. K. O. Sin, and P. K. T. Mok, “A novel ultrathin elevated channel low-temperature poly-Si TFT,” IEEE Electron Device Lett., vol. 20, pp. 569–571, Nov. 1999.

Copyright

Copyright © 2024 Varsheni. K, Megha D Prasad. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Download Paper

Paper Id : IJRASET60008

Publish Date : 2024-04-08

ISSN : 2321-9653

Publisher Name : IJRASET

DOI Link : Click Here

Submit Paper Online

Submit Paper Online