Ijraset Journal For Research in Applied Science and Engineering Technology

- Home / Ijraset

- On This Page

- Abstract

- Introduction

- References

- Copyright

Rejection Sensitivity, Adult Self-Expression, and Life Satisfaction in Single Child

Authors: Lamyah Hasana

DOI Link: https://doi.org/10.22214/ijraset.2024.59820

Certificate: View Certificate

Abstract

The purpose of the present study is to assess the role of rejection sensitivity, adult self-expression and life satisfaction in single child. The study also assesses whether there is significant relationship between rejection sensitivity, self-expression, and life satisfaction and also assess if there is any significant difference in gender with respect to rejection sensitivity, self-expression, and life satisfaction. A sample of 152 single child young adults aged between 18-26 years participated in the study. The Rejection Sensitivity Questionnaire-Adult Version (A-RSQ) by Downey, Berenson and Kang, Satisfaction with Life Scale (SWLS) by Diener, Emmons, Larsen and Griffin and Adult Self-Expression Scale (ASES) by Melvin L. Gay, James G. Hollandsworth and John P. Galassi were used to measure the variables in the study. The data were statistically analyzed using the independent sample t-test and Pearson\'s correlation coefficient. According to the results, all the variables are correlated to each other and rejection sensitivity, self-expression, and life satisfaction does not significantly differ based on gender.

Introduction

I. INTRODUCTION

In today's fast-paced and interconnected world, the impact of rejection on individuals has become increasingly complex and multifaceted. Rejection, whether in personal relationships, academic pursuits, professional endeavors, or even in the realm of social media, can have profound effects on people's mental and emotional well-being. One significant aspect of how rejection affects individuals in the modern world is through the prevalence of social media platforms. The constant comparison to curated and idealized versions of others' lives can intensify feelings of inadequacy and amplify the impact of rejection. Social media platforms, where individuals often showcase their achievements and positive experiences, can create a distorted perception of reality and exacerbate the fear of being left out or not measuring up.

The term "rejection sensitivity" describes a person's increased susceptibility to the prospect of being rejected in social settings. Even if rejection may not be objectively existent, it is frequently characterised by a strong emotional reaction to perceived or anticipated rejection. Although nobody likes to be rejected, some people are more vulnerable to rejection in social situations than others. People with strong rejection sensitivity experience everyday life-altering dread and aversion to rejection (De Rubeis et al., 2017). People who are sensitive to rejection often misunderstand, misrepresent, and overreact to the words and deeds of others due to their worries and expectations. They might even react with resentment and hurt. Rejection-sensitive people frequently misread or overreact to different facial expressions. One study, for example, discovered that when subjects saw a face that appeared as though it would reject them, their brain activity changed in proportion to their level of rejection sensitivity (Burklund et al., 2007). Through the use of functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), the researchers discovered that when people with higher rejection sensitivity saw faces that expressed disapproval, their brain activity changed. Rejection-sensitive people have higher levels of physiological activity when they fear rejection—more so than those who are not sensitive to rejection. Additionally, individuals who rank high in rejection sensitivity often pay more attention to rejection or signs that they were rejected. This is known as attention bias. On the other hand, a person with a low threshold for rejection can see the same situation as a huge success. People who have a high threshold for interpersonal rejection are obsessed with rejection in all its forms, real and perceived. They also pay close attention to other people's emotions and actions and are extremely perceptive to interpersonal issues.

There is no one factor that causes rejection sensitivity. Rather, a multitude of things might be involved. In addition to biological factors and genetics, some potential explanations include childhood experiences such as bullying and critical parents. Rejection sensitivity in the context of being a single child can be caused by a number of circumstances. The single child has often been stereotyped, in terms of their behaviour and capabilities. G Stanley Hall, pioneering American psychologist who focused on child development, had once (in)famously said that a lonely child was a “disease in itself”. Other theories over the years have also contributed to how an only child is perceived as oversensitive, lonely and sometimes, a misfit in the society.

Single children may receive undivided attention from their parents, which can foster a close emotional attachment. But since the youngster may not be used to sharing resources or attention with siblings, this could potentially make them more sensitive to any rejection. Their socialisation abilities might be impacted by the fact that they may not have as much exposure to peer interactions at home. When they do face social circumstances, their inexperience with understanding social dynamics may make them more vulnerable to rejection. Parents of single child may have high standards for their child's conduct and accomplishments. Because the youngster may feel under pressure to meet or beyond expectations in order to maintain approval, this pressure can exacerbate feelings of failure and rejection. Single children could not share the same experiences as those who have siblings because they won't encounter the interpersonal dynamics and arguments that frequently arise between siblings. Due to their narrow viewpoint, they may be more susceptible to feeling abandoned when disagreements or conflicts emerge.

Single children may also be more sensitive to rejection if they had a departed sibling. The impact of losing a sibling on rejection sensitivity varies depending on the child's age, the sibling's circumstances of death, and the support network that the child has. Single children who lose a sibling may feel empty, depressed, and alone. They may become more sensitive to rejection during the grieving process as they work through their feelings and adjust to the altered family dynamic. Parents going through a child loss may find it difficult to deal emotionally. The attention and focus of parents may temporarily shift towards coping with their grief, potentially leaving the single child feeling neglected or rejected. The dynamics and structure of the family may alter as a result of sibling loss. Changes in the single child's identity and position within the family may occur, which may exacerbate feelings of unease and rejection. Rejection sensitivity may be influenced by the degree of communication within the family regarding the loss and its effects. It is possible to lessen the chance that a single child would feel rejected by providing them with open and encouraging communication. A solid support network, such as sympathetic and understanding friends, family members, or counselling services, helps lessen the sensitivity to rejection. A healthier adjustment can be facilitated by having individuals in the child's life who offer emotional support and guide them through their sadness. When a sibling died suddenly or violently, children's reactions included long-term grief, loss, and impairments to their mental and physical health. Compared to accidental deaths, adult children experienced higher levels of remorse, shame, and rejection following a sibling's suicide (Mitchell et al., 2009). Lohan and Murphy discovered that teenagers exhibited multiple mourning reactions and behavioural alterations up to 2 years following their siblings’ untimely or violent deaths (Lohan & Murphy, 2002).

The assessment of one's life as a whole, rather than just their present state of happiness, is known as life satisfaction. “Life satisfaction is the degree to which a person positively evaluates the overall quality of his/her life as a whole. In other words, how much the person likes the life he/she leads” (Ruut Veenhoven, 1996). It speaks to a person's general sentiments regarding their existence. Put differently, life satisfaction is an overall assessment rather than one that is based on a particular period of time or area. Happiness and life satisfaction are not synonymous, despite their relationship. Harvard University psychology professor Daniel Gilbert claims that happiness is defined as "anything we pleased" (Gilbert, 2009). It is a more ephemeral concept than life satisfaction and is influenced by a vast array of situations, actions, and ideas. Life satisfaction is not only more stable and long-lived than happiness, it has a wider range of applications. It expresses how content we are with the way things are going in general and our life. Work, romantic relationships, interactions with family and friends, personal development, health and wellness, and other areas are just a few of the many variables that affect life happiness. Quality of life is another measure of happiness or wellbeing, but it is related with living conditions including the amount and quality of food, the status of one’s health, and the quality of one’s shelter (Veenhoven, 1996).

The impact of rejection sensitivity on a single child's life pleasure can be diverse. There may be a connection to low self-esteem. A child's confidence and self-perception may be impacted if they experience chronic rejection anxiety. Their general sense of wellbeing and self-satisfaction may be impacted as a result. A child's performance at work or in school might be hampered by their fear of criticism or failure, which can have an impact on their ability to grow in their job and further their education. This could therefore have an effect on life satisfaction because people frequently find fulfilment in their academic and professional endeavours. Greater susceptibility to anxiety and depression is linked to high rejection sensitivity. These mental health problems can have a major negative influence on general life satisfaction if they are not treated. People who are sensitive to rejection could resort to unhealthy coping mechanisms like hostility or avoidance in order to shield themselves from what they perceive to be rejection. These tactics may increase stress levels and have a detrimental effect on life happiness.

Self-expression is the process by which we share who we are, and it turns out that there are many different methods to accomplish it. It is vital to express oneself since doing so can make one happier in general by allowing one's inner peculiarities, traits, and qualities to be fully expressed. It enables someone to share with the outer world the most significant aspects of oneself. Self-expression raises a person's sense of fulfillment in life and helps them be recognized as unique individuals.

As a result, one may be able to build more genuine connections with people through authentic portrayals of oneself. People who have the ability to express themselves are happier, more cooperative, and more productive in life.

Self-expression can also improve one's health by encouraging coping mechanisms for stress. Stress can significantly lower a person's quality of life and is a risk factor for a number of disease processes. It lowers stress levels by giving creative expression a platform. Although to some degree, positive and negative emotions might be universally viewed as desirable and undesirable, respectively, there appear to be clear cultural differences in how relevant such emotional experiences are to quality of life (Kuppens et al., 2008). Greater life satisfaction occurs for individuals with high conscientiousness and openness to experience through the enjoyment derived from running and the expression of identity through running (Sato et al., 2018). Through self-expression, centrality, and attraction, conscientiousness has favorable indirect effects on life satisfaction. Through attraction and self-expression, being open to new experiences also enhanced life happiness inadvertently. Regardless of whether they have siblings or not, children who fear rejection may experience particular difficulties when it comes to expressing who they are. A child's readiness to freely express their thoughts, feelings, and opinions might be impacted by their fear of rejection. Children who are single might not have siblings with whom they can socialize and engage on a regular basis. They might also have less opportunity to interact with their friends, particularly if they don't regularly attend playdates or childcare. A lack of experience negotiating social dynamics and expressing oneself in a variety of social circumstances might result from limited social exposure. A child's social experiences and autonomy may be unintentionally restricted by overly protective parenting, which can make it difficult for them to express themselves freely.

II. METHOD

A. Objectives of the study

- To find out if there is any significant relationship between rejection sensitivity and life satisfaction in single child.

- To find out if there is any significant relationship between rejection sensitivity and adult self-expression in single child.

- To find out if there is any significant relationship between adult self-expression and life satisfaction.

- To study if there is any significant difference between males and females in rejection sensitivity.

- To study if there is any significant difference between males and females in life satisfaction.

- To study if there is any significant difference between males and females in self-expression.

B. Hypotheses

- Ho1: There is no significant relationship between rejection sensitivity and life satisfaction among single child.

- Ho2: There is no significant relationship between rejection sensitivity and adult self-expression in single child.

- Ho3: There is no significant relationship between adult self-expression and life satisfaction in single child.

- Ho4: There is no significant difference between males and females in rejection sensitivity.

- Ho5: There is no significant difference between males and females in life satisfaction.

- Ho6: There is no significant difference between males and females in self-expression.

C. Research Design

Correlational Research design is used in this study.

D. Variables

Independent Variable: Gender

Dependent Variable: Rejection sensitivity, Adult Self-expression, Life satisfaction

Demographic variables: Gender

E. Sample Distribution

In the present study, purposive sampling method was used to collect data from 152 participants including single children aged between 18-26 years.The study consisted of students, undergraduates, postgraduates and working individuals. The response was collected from the participants using the Google form which was a one-time response. The consent of the participant was taken before filling the Google form to participate in the current study.

F. Inclusion Criteria

- Single children aged between 18 to 26 years.

- Residents of India.

- Single children who lost their siblings are also included.

G. Exclusion Criteria

- The participants who don’t fall between the age group of 18 to 26 years.

- Who are not Indian residents.

- Samples from a clinical population are also excluded.

H. Research Ethics Followed

- Informed consent of participant taken

- Anonymity of the participant maintained

- Confidentiality maintained

I. Tools for the study

- The Rejection Sensitivity Questionnaire-Adult Version (A-RSQ) by Downey, Berenson and Kang (2009).

- Adult Self-Expression Scale (ASES) by Melvin L. Gay, James G. Hollandsworth and John P. Galassi (1977).

- Satisfaction with Life Scale (SWLS) by Diener, Emmons, Larsen and Griffin (1985).

J. Description of the tool

- The Rejection Sensitivity Questionnaire-Adult Version (A-RSQ) by Downey, Berenson and Kang (2009).

A 9- item scale with scoring of scale 1 to 6, very unconcerned/unlikely to very concerned/likely. Calculate a rejection sensitivity score for each situation by multiplying the level of rejection concern (the response to question a) by the level of rejection expectancy (the reverse of the level of acceptance expectancy reported in response to question b). The total rejection sensitivity score is the mean of the rejection sensitivity scores for the 9 situations. Internal consistency (alpha) = .89 (for each administration) and test–retest reliability (spearman–brown coefficient) = .91. Validity is construct validity.

2. Adult Self-Expression Scale (ASES) by Melvin L. Gay, James G. Hollandsworth and John P. Galassi (1977).

This 48-item assertiveness instrument was developed to measure assertiveness in adults. Test-retest reliability was determined for a two-week period (r = .88) and for a five-week period (r = .91), which suggests the ASES is a stable measure of assertiveness. Concurrent validity is evidenced with correlations between the ASES.

3. Satisfaction with Life Scale (SWLS) by Diener, Emmons, Larsen and Griffin (1985).

A 5-item scale designed to measure global cognitive judgments of one’s life satisfaction participants indicate how much they agree or disagree with each of the 5 items using a 7-point scale that ranges from 7 strongly agree to 1 strongly disagree. Though scoring should be kept continuous (sum up scores on each item), here are some cutoffs to be used as benchmarks. 31 - 35 extremely satisfied. 26 - 30 satisfied. 21 - 25 slightly satisfied. 20 neutral. 15 - 19 slightly dissatisfied. 10 - 14 dissatisfied. 5 - 9 extremely dissatisfied. The analysis of the scale’s reliability showed good internal consistency (α = 0.74), and shows good convergent validity.

K. Statistical Analysis

The results were analyzed using descriptive and inferential statistics. IBM SPSS- 25 was used for data analysis. Among descriptive statistics, mean and standard deviation were used, among the inferential statistics independent sample t-test and Pearson’s correlation method was used to test the hypothesis.

III. RESULT AND DISCUSSION

Ho1: There is no significant relationship between rejection sensitivity and life satisfaction among single child.

Table 1 N, M, SD, and correlation for rejection sensitivity and life satisfaction

|

Variable |

n |

M |

SD |

1 |

|

A-RSQ |

152 |

10.02 |

3.10 |

_ |

|

SWLS |

152 |

22.63 |

7.15 |

-.322** |

|

|

|

|

|

|

**Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level

Table 1 shows the total number of samples, mean, SD, and correlation coefficient between rejection sensitivity and life satisfaction among single child. The mean of A-RSQ and SWLS is 10.02 and 22.63 respectively. The standard deviation of A-RSQ and SWLS is 3.10 and 7.15 respectively. Results show that life satisfaction is negatively correlated with rejection sensitivity with a Pearson correlation coefficient of -0.322. The correlation is significant at 0.01 level and the significance value is less than 0.01, the null hypothesis is rejected and H1 is accepted. That is, there is significant relationship between rejection sensitivity and life satisfaction in single child.

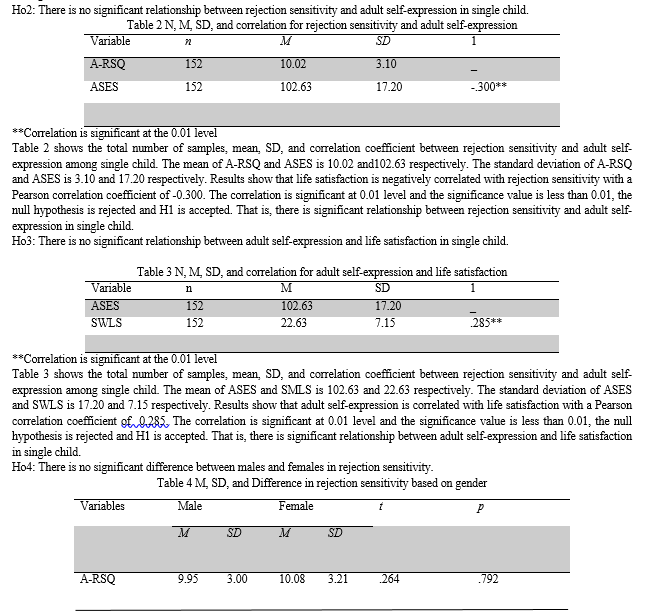

Ho2: There is no significant relationship between rejection sensitivity and adult self-expression in single child.

Table 2 N, M, SD, and correlation for rejection sensitivity and adult self-expression

|

Variable |

n |

M |

SD |

1 |

|

A-RSQ |

152 |

10.02 |

3.10 |

_ |

|

ASES |

152 |

102.63 |

17.20 |

-.300** |

|

|

|

|

|

|

**Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level

Table 2 shows the total number of samples, mean, SD, and correlation coefficient between rejection sensitivity and adult self-expression among single child. The mean of A-RSQ and ASES is 10.02 and102.63 respectively. The standard deviation of A-RSQ and ASES is 3.10 and 17.20 respectively. Results show that life satisfaction is negatively correlated with rejection sensitivity with a Pearson correlation coefficient of -0.300. The correlation is significant at 0.01 level and the significance value is less than 0.01, the null hypothesis is rejected and H1 is accepted. That is, there is significant relationship between rejection sensitivity and adult self-expression in single child.

Ho3: There is no significant relationship between adult self-expression and life satisfaction in single child.

Table 3 N, M, SD, and correlation for adult self-expression and life satisfaction

|

Variable |

n |

M |

SD |

1 |

|

ASES |

152 |

102.63 |

17.20 |

_ |

|

SWLS |

152 |

22.63 |

7.15 |

.285** |

|

|

|

|

|

|

**Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level

Table 3 shows the total number of samples, mean, SD, and correlation coefficient between rejection sensitivity and adult self-expression among single child. The mean of ASES and SMLS is 102.63 and 22.63 respectively. The standard deviation of ASES and SWLS is 17.20 and 7.15 respectively. Results show that adult self-expression is correlated with life satisfaction with a Pearson correlation coefficient of 0.285. The correlation is significant at 0.01 level and the significance value is less than 0.01, the null hypothesis is rejected and H1 is accepted. That is, there is significant relationship between adult self-expression and life satisfaction in single child.

IV. IMPLICATIONS

"Rejection sensitivity, self-expression, and life satisfaction in single children" is a study that most likely looks at the connections between these factors in single children. The results of the study could provide insight into how being raised as a single child affects a person's psychological health, especially with regard to their susceptibility to rejection and capacity for self-expression. Gaining an understanding of these dynamics might help one better understand the special difficulties and advantages that come with being the only child. It might make clearer how social interactions and relationships among single children are impacted by rejection sensitivity, which is defined as the propensity to anxiously anticipate, rapidly perceive, and overreact to rejection. In order to assist the social development of single children, parents, educators, and mental health specialists can all benefit from this information. The study may look at how self-expression—that is, the capacity to share one's ideas, emotions, and experiences—affects single children's identity development and general level of life happiness. Interventions intended to support healthy identity formation and well-being can be informed by an understanding of the function that self-expression plays in this setting.

The study's conclusions may provide direction to parents of single children on how to help them develop social skills, resilience, and self-assurance. It might also emphasise how crucial it is to provide supportive environments for single children to assist them deal with social obstacles and improve their general sense of happiness with life, both inside the home and in larger societal situations. The findings of this study could have an impact on educational environments and therapeutic interventions designed to assist single children who could be more sensitive to rejection or struggle with self-expression. The results of the study could guide strategies for fostering social-emotional learning, developing coping mechanisms, and raising self-esteem. Overall, the implications of this study could contribute to a better understanding of the psychological dynamics unique to single children and inform efforts to support their well-being and development in various contexts.

V. SUGGESTIONS FOR FUTURE RESEARCH

The future study can include other socio-demographic details. More sample size can be helpful in generalizing the result. More geographical area may be covered for future studies. More variables could be added to assess more detailed characteristics about the population. More than one population could be added for the purpose of comparison.

VI. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The author appreciates all those who participated in the study and helped to facilitate the research process

Conflict of interest: The author declared no conflict of interests.

References

[1] Bhutani, G. M. & Tara, D. (2023). Relationship between Childhood Neglect and Rejection 2817. DIP:18.01.266.20231103, DOI:10.25215/1103.266. [2] Burklund, L. J., Eisenberger, N. I., & Lieberman, M. D. (2007). The face of rejection: Rejection sensitivity moderates dorsal anterior cingulate activity to disapproving facial expressions. Social Neuroscience, 2(3–4), 238–253. https://doi.org/10.1080/17470910701391711 [3] De Rubeis, J., Lugo, R. G., Witthöft, M., Sütterlin, S., Pawelzik, M. R., & Vögele, C. (2017). Rejection sensitivity as a vulnerability marker for depressive symptom deterioration in men. PLOS ONE, 12(10), e0185802. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0185802 [4] Khaleque, A., Uddin, M. K., Hossain, K. N., Siddique, M. N., & Shirin, A. (2019). Perceived Parental Acceptance–Rejection in childhood predict psychological adjustment and rejection sensitivity in adulthood. Psychological Studies, 64(4), 447–454. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12646-019-00508-z [5] Kraines, M. A., Kelberer, L. J., & Wells, T. T. (2018). Rejection sensitivity, interpersonal rejection, and attention for emotional facial expressions. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry, 59, 31–39. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbtep.2017.11.004 [6] Kuppens, P., Realo, A., & Diener, E. (2008). The role of positive and negative emotions in life satisfaction judgment across nations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 95(1), 66–75. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.95.1.66 [7] Lee, Y. J. (2023). Analysis of Structural Relationships among Adult Attachment, Rejection Sensitivity, Ambivalence over Emotional Expressiveness and Social Anxiety of University Students. Korean Association for Learner-Centered Curriculum and Instruction, 23(15), 931–947. https://doi.org/10.22251/jlcci.2023.23.15.931 [8] McLachlan, J. A., Zimmer?Gembeck, M. J., & McGregor, L. (2010). Rejection sensitivity in childhood and early adolescence: peer rejection and protective effects of parents and friends. Journal of Relationships Research, 1(1), 31–40. https://doi.org/10.1375/jrr.1.1.31 [9] Mitchell, A. M., Sakraida, T. J., Kim, Y., Bullian, L., & Chiappetta, L. (2009). Depression, Anxiety and Quality of Life in suicide Survivors: A comparison of Close and Distant relationships. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing, 23(1), 2–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apnu.2008.02.007 [10] Ni, X., Li, X., & Wang, Y. (2021b). The impact of family environment on the life satisfaction among young adults with personality as a mediator. Children and Youth Services Review, 120, 105653. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2020.105653 [11] Pollmann?Schult, M. (2014). Parenthood and life satisfaction: Why don’t children make people happy? Journal of Marriage and the Family, 76(2), 319–336. https://doi.org/10.1111/jomf.12095 [12] R, J. C., & KM, R. (2022). RESILIENCE, REJECTION SENSITIVITY AND ANGER AMONG ADULTS WITH MIDLIFE CRISIS. INDIAN JOURNAL OF APPLIED RESEARCH, 36–37. https://doi.org/10.36106/ijar/3401451 [13] Sato, M., Jordan, J. S., Funk, D. C., & Sachs, M. L. (2018). Running involvement and life satisfaction: The role of personality. Journal of Leisure Research, 49(1), 28–45. https://doi.org/10.1080/00222216.2018.1425051 [14] Sen, N., Suri, K., & Jain, S. (2020). Sexting, rejection sensitivity and social motivation among dating and non-dating young adults: a comparative analysis. International Journal of Indian Psychology, 8(4). https://doi.org/10.25215/0804.052 [15] Sensitivity in Indian Adults. International Journal of Indian Psychology, 11(3), 2810- [16] Son, J., & Park, J. H. (2019). The Effects of Parentification of Early Adult Non-disabled Siblings on Ambivalence over Emotional Expression and Moderating Effects of Rejection Sensitivity. Family and Environment Research, 57(3), 445–457. https://doi.org/10.6115/fer.2019.033 [17] Watson, J., & Nesdale, D. (2012b). Rejection sensitivity, social withdrawal, and loneliness in young adults. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 42(8), 1984–2005. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1559-1816.2012.00927.x

Copyright

Copyright © 2024 Lamyah Hasana. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Download Paper

Paper Id : IJRASET59820

Publish Date : 2024-04-04

ISSN : 2321-9653

Publisher Name : IJRASET

DOI Link : Click Here

Submit Paper Online

Submit Paper Online