Ijraset Journal For Research in Applied Science and Engineering Technology

- Home / Ijraset

- On This Page

- Abstract

- Introduction

- Conclusion

- References

- Copyright

Relationship between Dating Violence and Resilience among Young Adults

Authors: Krishnamurthy Sri Vidya , Dr. Sruthi Sivaraman

DOI Link: https://doi.org/10.22214/ijraset.2024.61299

Certificate: View Certificate

Abstract

The study looks into the connection between resilience and dating violence. The results point to the significance of including ways to build Resilience for victims of dating violence. To help survivors\' resilience, therapists could concentrate on improving coping strategies, self-esteem, and social support systems. To lessen the harmful effects of dating violence, education and preventative initiatives should place a strong emphasis on young people developing resilience skills. With the use of this data, measures should be taken that will lessen dating violence and increase access to tools that foster resilience in contexts such as schools, colleges, etc . This can entail setting aside funds for support groups, counseling services, and awareness campaigns. It is necessary to do additional study to investigate the precise processes by which resilience mitigates the impact of dating violence. The long-term effects of resilience on relationships and mental health outcomes may be better understood through longitudinal research. Furthermore, assessing the success of programmes that emphasize resilience may help direct future efforts in practice and policy. It\'s critical to take into account the ways that experiences of dating violence and resilience are influenced by variables including gender, race, sexual orientation, and socioeconomic background. Promoting inclusivity and efficacy requires designing interventions to meet the specific requirements of diverse communities.

Introduction

I. INTRODUCTION

A. Dating Violence

It is helpful to first examine definitional components of the construct of dating aggression before delving into prevention programmes that have been put into place to combat violence in dating relationships. The scope and purpose of the violent behaviors that take place in romantic relationships are very diverse. Physical force, whether in the form of threats or actual acts of physical aggression, is the most evident manifestation of dating violence. This is the kind of violent behavior that is examined and evaluated the most frequently.

The definition of dating violence put forth by Sugarman and Hotaling (1989)—"the use or threat of physical force or restraint carried out with the intent to causing pain or injury to another" (p. 5)—is widely accepted by researchers in an attempt to define the concept in a parsimonious manner. The content of the most widely used assessment tools for gauging intimate partner aggression reflects this operational concept. (Lewis & Fremouw., 2001)

While emphasizing overt physical aggression has its benefits, it ignores other forms of coercive or violent behavior that are frequently seen in romantic relationships and may serve a similar purpose to physical violence. (Hanley & O'Neill., 1997; Jackson., 1999; Murphy & Hoover, 2001; Riggs & O'Leary., 1996; Shook, Gerrity, Jurich, & Segrist., 2000). While the 1989 term by Sugarman and Hotaling is still widely used in literature, more recent formulations have started to incorporate sexual, psychological, and physical kinds of violence. (Lavoie et al., 2000) Dating violence is defined as "any behavior that comprises the physical, psychological, or sexual integrity of the partner in a way that is detrimental to their development or health" (p. 8). Furthermore, according to certain analyses, any behavior that aims to “...control or dominate another person physically, sexually, or psychologically, causing some level of harm” is included in the definition of interpersonal violence. (Wekerle & Wolfe., 1999).

Victims of dating violence (DV) are teenagers who participate in a range of harmful partner-directed behaviors, including psychological, physical, and sexual ones. Emotionally manipulative acts intended to unintentionally cause harm to a partner are referred to as psychological domestic violence. Physical DV includes actions like pushing, slapping, punching, kicking, choking, and burning. Sexual DV includes forced sexual activity, which can include anything from forced penetration to unwanted touching. The primary foci of this study include relational, emotional, and verbal-emotional physical and psychological DV. (Lane, K., & Gwartney-Gibbs, P., 1985)

A serious public health concern, domestically and globally, DV has been increasing worse recently. Studies have shown that adult dating relationships involve violence on par with or even higher than that of domestic relationships. It is during adolescence that violent issues initially surface, not in adult relationships.. It is essential to approach domestic violence (DV) from a multicausal viewpoint, as it is a phenomenon conditioned by the interaction of both individual and interpersonal variables. A great deal of attention has been paid in the scientific literature to family traits, including parenting styles, which have been connected to bullying or cyberbullying behaviors , peer violence , and other interpersonal factors that are associated with aggression (Roscoe, B., & Kelsey, T., 1986).

Domestic violence has been attempted to be explained by a number of theoretical frameworks. The most well-known theories include the social learning theory, the background/situational model, the feminist theory, the power theory, and the personality/typology model ( Bell and Naugle's review., 2008). Bell and Naugle's alternative theoretical conceptualization of intimate partner violence could serve as a theoretical framework for this study, providing a coherent integration of past theories on domestic violence (DV). In this model, Bell and Naugle divide the causes, behavioral repertoire, linguistic norms, motivational variables, antecedents, and results of intimate relationship violence. The purpose of this research is to shed more light on the distinct behavioral repertoires of TDV perpetrators and victims. The term "behavioral repertoire" refers to a person's socially adaptive skill sets that they may effectively employ in appropriate circumstances to accomplish a desired result. Adolescents engaged in trafficking in women may display a variety of behavioral deficits, such as maladjustment characteristics and attitudes (particularly sexist attitudes) and deficiencies in adjustment qualities (resilience and self-worth) (Ak?? N., Korkmaz, N.H., Taneri, P.E., Özkaya, G., & Güney, E., 2019).

It's also critical to look at DV from a developmental perspective. Most romantic partnerships begin in adolescence. Teens observe and learn a lot about relationships in their friends' and family's lives, as well as from the media, about romantic relationships. Adolescence is characterized by a high frequency of narcissism, an exaggeration of gender-specific roles (male dominance and female submission), and a mystique surrounding romance, all of which make teenage relationships especially vulnerable to violence.

Dating-related increased emotional experiences might occasionally show out as animosity towards the partner. This animosity could be shown verbally, physically, or mentally. As physical aggression is perhaps the most evident, early intervention or preventative actions are required (Alptekin, D.,2014).

However, another form of aggression that frequently appears in teenage love relationships is relational aggression, which involves verbal or psychological violence (insults or intimidation). The definition of relational aggression used in this study is in line with that of Ellis, Crooks, and Wolfe, who define it as behaviors meant to undermine the victim-perpetrator bond or exercise social control. This article's goal is to provide more information that might be included into different DV prevention and intervention programmes while also delving deeper into the implications of this phenomenon. Moreover, TDV impacts both genders equally. Men make up a larger percentage of offenders (7.5% to 37.8%) than do women (7.1% to 14.9%), according to research done in Spain Some authors argue that these results are understandable given Spain's historically conservative culture, which values men as strong and aggressive and women as delicate and submissive. Contrary to these findings, some research indicates that women commit crimes at higher rates than men (Aslan, D.,Vefikulucay,D.,Zeynelo?lu, S., Erdost, T., & Temel, F., 2008)

(Fernández-Fuertes, Fuertes, Fernández-Rouco, and Orgaz., 2001) suggest that gender socialization may be changing, but more research is needed. Studies conducted both domestically and internationally appear to indicate that women experience victimization at a higher rate than men, with rates for men ranging from 3.6% to 7.8% and for women from 7.9% to 15.5% . A person's propensity for aggression is said to decline with age, however even if people are less likely to use violence as they get older, the consequences are usually much worse.

When it comes to victimization, younger girls appear to be more aggressive than older women .

The disparity in reported prevalence rates may be explained by variations in the conceptualization of TDV and, more specifically, whether the typology of violence was taken into account in these studies. Accordingly, studies show that verbal (verbal-emotional or psychological) violence is the most common kind, with prevalence rates varying from 11% to 90% . Carver, Joyner, and Udry have observed that this type of violence increases with advancing years (Billingham, R., 1987).

According to longitudinal study, teens may be able to regulate their physical aggression as they get older, but they may find it very difficult to control their verbal-emotional hostility . Moreover, as verbal-emotional aggression is the most prevalent form of violence against youth, it is more challenging to remove.(Jackson, S. M., 1999).

B. Resilience

Resilience is defined as positive adaptability or the ability to preserve mental health in the face of adversity. However, as (Herrman et al., 2011) points out, resilience lacks a precise practical definition. 2. Resilience's psychological component enables people to maintain their mental health and wellbeing in the face of adversity as well as during the healing process following trauma. People can continue to be productive at work and at home thanks to the behavioral component of resilience, which helps them concentrate on and finish key projects and objectives (Robertson & Cooper., 2013). The coronavirus sickness 2019 (COVID-19) was caused by the 2019 novel coronavirus SARS-CoV-2 outbreak, which started in China's Wuhan region and quickly spread to Europe and the rest of the world (Zhou et al., 2020). A global public health issue, the COVID-19 epidemic has a major impact on people's life and mental health in many different ways. Maintaining a good balance and managing stress require resilience. Historically, resilience has not been measured as the capacity to recover from setbacks, withstand disease, cope with stress, or flourish in the face of hardship. Instead, resilience has been measured in terms of protective factors or resources that include coping mechanisms and personal traits. The Resilience Scale (Wagnild & Young., 1993), for instance, was designed to evaluate existential aloneness, equanimity, perseverance, self-reliance, and meaningfulness. In a similar vein, the Davidson-Connor Resilience Scale (Connor & Davidson., 2003) aimed to assess characteristics such as self-efficacy, sense of humor, patience, optimism, and faith

Resilience, according to (Daigneault., 2007), is the capacity to cope constructively with adversity, which might include early exposure to violence. (Klibert et al., 2014) state that a variety of factors influence resilience, such as the capacity to find meaning and purpose amid change and conflict and the ability to effectively manage difficulties, all of which support elevated wellbeing and life satisfaction (p. 75). However, other situations prevent resilience from developing, which can cause psychological distress and reduce confidence in one's ability to resolve or overcome conflicts (Klibert et al.,2014). According to (Klibert et al., 2014), there is evidence linking college students who exhibit low resilience to several adverse consequences, such as neuroticism, depression, and anxiety/stress. In fact, it appears that young adults are particularly susceptible to the lack of resilience. Resilient people in relationships may find it harder to endure conflicts that escalate into violent or aggressive confrontations. This is particularly important given studies that show a connection between resilience and enhanced problem-solving skills, a more optimistic view of conflict, and successful conflict resolution (Klibert et al., 2014).

Although the advantages of resilient functioning are clear, building resilience is a more complex process. (Seery et al., 2010) state that experiencing some tragedy in life can make a person more resilient. Specifically, (Seery et al., 2010) found that a history of some lifetime adversity predicted lower levels of post-traumatic symptoms, lower levels of global distress, and higher levels of life satisfaction compared to both no and high adversity. These results support the theory that resilience is the ability to withstand adversity via the use of social and psychological resources.On the other hand, surviving hardship can make a person more resilient in the long run (Seery et al., 2010) . (Seery et al., 2010) posit that experiencing adversity, no matter how slight, can foster the development of coping strategies, a sense of mastery over past struggles, a stronger belief in one's ability to overcome hardships in the future, and psychophysiological toughness.

In order to distinguish between at-risk adolescents exposed to interparental violence and those who experienced (perpetrated and were victims of) dating violence, resilience components were found to be significant. Male self-esteem arose as a protective characteristic that distinguished those who engaged in dating violence from those who did not, claims (O'Keefe., 1998). According to (O'Keefe., 1998), this finding is consistent with past research on resilience, which found that one resilience feature that helps shield at-risk youngsters is good self-esteem.

Males who see interparental violence are more likely to engage in dating violence themselves, according to research by (O'Keefe., 1998). Low socioeconomic position, exposure to violence in the community and at school, and acceptance of dating violence are additional susceptibility factors that raise the risk of encountering dating violence. When women were exposed to both community and school violence as well as child abuse, there was a greater association between their observation of interparental violence and their participation in dating violence (O'Keefe., 1998).

Males who see interparental violence are more likely to engage in dating violence themselves, according to research by (O'Keefe., 1998). Low socioeconomic position, exposure to violence in the community and at school, and acceptance of dating violence are additional susceptibility factors that raise the risk of encountering dating violence. When females were exposed to both community and school violence as well as child abuse, there was a greater association found between witnessing parental violence and participating in violent dating practices (O'Keefe.,1998).

(O'Keefe., 1998) draws attention to the dearth of studies on exposure to violence in the community and in educational settings, despite the fact that understanding this type of exposure is crucial to understanding how peer relationships support and legitimize partner violence. Both exposure scenarios are examined in this current inquiry

II. REVIEW OF LITERATURE

"A Thin Line Between Love and Hate": a study by Jenkins (2017)stated descriptions of Black men's experiences with and perpetrators of dating violence, according to Black Men as Victims and Perpetrators of Dating Violence. For example, in their 1972 rhythm-and-blues hit song A Thin Line Between Love and Hate, the Persuaders spoke of intimate partner abuse. The singer clarified that "I'm just getting in" at 5:00 a.m. Rather than becoming irate, his partner answered the door, took his coat, and made him an offer for dinner.The woman was kind at first, but after she attacked him, he was admitted to the hospital with "bandages from foot to head." In recent times, hip hop musicians have depicted sexual assault and violence against women with sexist lyrics and a funky beat (Adams & Fuller., 2006). The message remains the same regardless of the soundtrack: Some African American couples experience a lot of violence and grief in their lives. These intimate partners must collaborate with community members, therapists, advocates, and other relevant parties to build healthier relationships and more suitable dispute resolution techniques. Far fewer Black men and women will step over the tiny line into hate if this goal is successful. (C. M. West., 2008).

According to a systematic scoping review of reviews titled exploring risk and protective factors for dating violence across the social-ecological model (Claussen, Matejko & Exner-Cortens,2022). (n = 7) the most common risk factors for ADV perpetration at the individual level, followed by mental health conditions and psychological difficulties (n = 5). The most prevalent relationship risk factor for perpetration (n = 8) was a history of and/or present experience of child abuse and neglect, followed by seeing family violence (n = 7). Additionally, it was shown that bullying was a frequently mentioned relational risk factor (n = 5). On the other hand, having supportive and positive family relationships and positive peer networks were the main protective factors at the relational level (n = 4 and n = 1, respectively). In general, there were far fewer publications that addressed victimization; nonetheless, risk factors related to gender (being female) (n = 1) and mental health (n = 1) were mentioned on an individual basis. Having an older partner was linked to a higher risk of ADV at the relationship level (n = 2).In 2022, Claussen, Matejko and Exner-Cortens found a thorough scoping assessment of reviews investigating protective and risk factors for teenage dating violence throughout the social-ecological model (Carlson, B. E., 1987).

(Bowleg, Huang, Brooks, Black & Burkholder, G., 2003) interpreted their experiences of stress linked to heterosexism and sexism via the lens of racism and race. As anticipated, some individuals talked about experiencing ambiguous stress because they weren't sure if a stressor was brought on by heterosexism, sexism, or racism. Our results thus offer empirical validation for (Greene's., 1995) description of the "triple jeopardy" experience of Black lesbians. Finally, we expected the women in our study to be resilient, as operationalized by the six predictors of (Kumpfer's., 1999) transactional model of resilience, despite, or perhaps in response to, this triple peril of racism, sexism, and heterosexism. The idea of resilience among the Black lesbians surveyed for this study was corroborated by our results.

The likelihood of behavior change is unlikely without a skill-building component that integrates specific training to improve proficiency of communication, negotiation, and problem-solving skills according to (Cornelius & Resseguie., 2007), primary and secondary prevention programs for dating violence: A review of the literature. Aggression and violent behavior, 12(3), 364-375. These are undoubtedly important aspects of dating violence. While some of the programmes mentioned in the literature did include some minimal skill-building elements, these elements must be consistently and methodically included in order to provide alternative responses to dating violence, either in the present (secondary prevention) or in future relationships (primary prevention) (Foshee, 1996, 1998; & Macgowan., 1997). For instance, only one (the final) of Rosen and Bezold's nine-week preventive program's sessions included particular instruction in conflict-resolution and decision-making techniques.

The study was conducted by (O'KEEFE., 1997) found that men were more likely to harm a romantic partner if they had seen more instances of violence between parents and children, thought that violence between men and women in relationships was acceptable, used drugs or alcohol, were the victims of violence in relationships, and had more conflict in their relationships overall. Women were more likely to use violence against a romantic partner if they felt that relationships between men and women could not be justified, felt that there was more conflict in the relationship, experienced violence themselves, used drugs or alcohol, and thought the relationship was more serious. The study's ramifications were discussed as well as the background of the violence.

According to (Bookwala, Frieze, Smith, & Ryan., 1992) considering the results for females, it appears that a woman is most likely to be violent toward her partner when he is aggressive to her physically, when she is verbally aggressive, when she is violent in other contexts, and when she experiences romantic jealousy in the relationship. Having traditional gender role beliefs was also predictive of female physical aggression, as were the lack of a belief in adversarial relations between women and men. For men, the expression of violence was predicted by engaging in verbal aggression against their female partners as well as the endorsement of the belief that relations between men and women are inherently hostile; however, violent males were not necessarily violent in other contexts.

Contrary to our predictions, holding less traditional sex-role attitudes was predictive of expressed violence for men. Although this finding is unexpected, some support for it is forthcoming from research on marital violence which has found violent husbands to be lower in masculinity (Rosenbaum., 1986). Perhaps lower masculinity among some men is associated with fewer traditional inhibitions against violence directed at women.

(Bergman, L.,1992) stated that 15.5% of girls reported experiencing sexual violence, and the same percentage applied to physical violence. But it increased to 24.6% of those who reported either physical or sexual abuse, or both. Less male respondents reported violence overall: 7.8 percent reported physical violence, 4.4 percent reported sexual violence, and 9.9 percent reported both physical and sexual violence. Dating habits, grade point average, and the student's community were all significant determinants of violence. Although respondents claimed that violence had a tendency to repeat, they did not tell authorities or parents about this.

(Gover, Kaukinen & Fox., 2008) stated the connection between childhood violence and relationship violence—also referred to as the intergenerational transfer of violence—has historically concentrated on physical violence. This study looks at the connection between exposure to violence in the family of origin and engaging in or inflicting dating violence. In particular, the current study looks at gender disparities in the link between childhood exposure to violence and both perpetration and victimization of physical and psychological abuse. At two colleges in the Southeast, a sample of about 2,500 college students provided the data. Results show that both male and female involvement in violent relationships is consistently predicted by early exposure to violence.

(Offenhauer & Buchalter., 2011) stated in a research study about the unspoken social problems of the 1980s is violence in adolescent romantic relationships. In a poll of 256 high school students in a school district in Sacramento, California, it was discovered that 35.1% of the students had been abused in a dating relationship. It was also investigated how severe the violence was and how intergenerational it was.

(Molidor & Tolman., 1998) claims that a dating violence questionnaire that contained items adapted from the Conflict Tactics Scales was used to poll 635 high school students. The comparison of male and female experiences of victimization in past and present romantic relationships was the main focus of the analyses. The total frequency of violence in dating relationships did not differ between male and female teenagers, which is consistent with several earlier studies. Adolescent girls, on the other hand, had more severe physical and mental reactions to the abuse and experienced significantly greater levels of severe violence.

(Foshee, Linder, MacDougall, & Bangdiwala., 2001) conducted cross-sectional studies that revealed a correlation between the majority of research variables and dating violence. The likelihood that a female will commit dating violence was predicted by drinking alcohol, having acquaintances who have experienced dating violence, and being a non-white race. Males were more likely to commit dating violence when they held attitudes that were accepting of it. According to the findings, different intervention strategies should be used for men and women. Additionally, if interventions are based solely on cross-sectional data, limited resources may be used to treat people who are not actually at danger of starting to engage in dating violence.

(Bethke & DeJoy., 1993) found that individuals were more accepting of aggressive behavior when it involved a significant relationship and a female aggressor. Relationship status had an impact on the acceptability and appropriateness of different measures that could be performed in the wake of the incident, especially those that would change or terminate the relationship. Male aggression was viewed as less acceptable, more harmful, and more criminal. Furthermore, it was believed that male victims required less recourse or reparation than their female counterparts. Subjects that were male and female had very identical histories of dating violence (both as perpetrators and victims), and responses to the dating situations were unaffected by prior experience.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2006) stated the 18-month prevalence of victimization from physical and psychological dating violence was assessed to be 12% and 20%, respectively, in a research conducted in 1994-1995 among students in grades 7–12. Victims of dating violence face increased risks of harm and death, as well as unsafe sexual behaviour, bad dietary habits, substance abuse, and suicide thoughts and attempts. Intimate partner violence (IPV), particularly against women, can have its roots in dating violence victimisation.An estimated 5.3 million incidences of intimate partner violence (IPV) among adult women in the US are reported annually, with an estimated 2 million injuries and 1,300 fatalities (Truman-Schram, D. M., Cann, A., Calhoun, L., & Vanwallendael, L.,2000).. The CDC examined the frequency of physical dating violence (PDV) victimization among high school students and its correlation with five risk behaviors using data from the 2003 Youth Risk Behaviour Survey (YRBS). The findings showed that 8.9% of students—8.9% of men and 8.8% of women—reported having experienced domestic violence in the 12 months prior to the survey, and that those who did so were more likely to have participated in four of the five risk behaviours (i.e., engaging in sexual activity, attempting suicide, binge drinking on occasion, and physical fighting). In order to teach high school pupils about positive dating behaviors, primary prevention programmes are required.

(Price, E. L., Byers, E. S., Belliveau, N., Bonner, R., Caron, B., Doiron, D., & Moore, R., 1999) claimed that a total of 823 pupils enrolled in grades 7, 9, and 11 took part in the validation research. There is high internal consistency across all six scales. It was expected that students would be more tolerant of girls using violence than of guys, and that boys would be more tolerant of violence than girls. The construct validity of the six scales was supported by the positive correlations they showed between traditional attitudes about gender roles and among themselves. The AMDV Scales' criterion-related validity was supported by the correlations between boys' higher scores and their aggressive peers and past usage of violence in romantic relationships. A portion of the criterion-related validity of the AFDV Scales was supported by the finding that higher scores were linked to females' prior usage of dating violence but not to their presence of violent companions. The Attitudes Towards Dating Violence Scales, either alone or in combination, can be used to improve our knowledge of how attitudes that encourage violence develop and persist in adolescents of all ages.

According to (Draucker, C. B., & Martsolf, D. S., 2010) the individuals had experienced a range of forms of violence as teenagers, from one isolated instance of moderate verbal abuse by one relationship to ongoing, severe physical, verbal, and sexual assault by several partners. Although one partner was frequently the main aggressor, the majority of individuals recounted situations in which both partners were violent. Just one person reported experiencing violence from their same-sex partner.

Regression studies revealed that the couple's communication habits were substantially correlated with relationship satisfaction and the duration of the dating relationship, as per the findings of (Follette & Alexander., 1992) claimed that male communication habits were linked to physical aggressiveness in dating relationships, while women in violent relationships reported lower levels of relationship satisfaction.

(Follingstad, Wright, Lloyd, & Sebastian., 1991) revealed that men seemed to undervalue the impacts of physical assault on women, while women reported more emotional and physical injuries than men.

(Foshee, V. A., Bauman, K. E., Arriaga, X. B., Helms, R. W., Koch, G. G., & Linder, G. F., 1998) claimed that less sexual assault, psychological abuse, and aggression against the present romantic partner were recorded in treatment than in control schools in the entire sample at the follow-up. There was a lower rate of psychological abuse initiation in treatment compared to control schools in a subsample of teenagers who reported no dating violence at baseline (a primary prevention subsample). Less psychological abuse and sexual violence perpetration was observed at follow-up in treatment than in control schools in a subsample of adolescents who reported dating violence at baseline (a secondary prevention subsample). Most program effects were explained by changes in dating violence norms, gender stereotyping, and awareness of services. Conclusions: The Safe Dates program shows promise for preventing dating violence among adolescents

(Arriaga, X. B., & Foshee V. A.,2004).states that the likelihood of dating violence may also rise if one's peers are involved in violent relationships. The authors looked at either antecedent—friend dating violence or, if either, interparental violence—is more likely to predict the commission and victimization of one's own dating violence. Over the course of six months, 526 adolescents, or eighth and ninth graders, answered self-report questionnaires twice. In line with the theories, there were distinct cross-sectional correlations between victimization and perpetration for both friend dating violence and interparental violence. Only friend violence, though, was a reliable indicator of subsequent dating violence. In order to explain the connection between friends and their own dating violence, the authors looked at selection processes versus influence.

(Wekerle & Wolfe, 1998;& Wolfe et al., 1996, 1997) stated that instead of focusing just on the negative behaviors, those who work with child abusers educate parents with positive skills so they can provide them healthy alternatives to coercive ways. Additionally, certain programmes' focus on health promotion abilities, like help seeking behavior (Foshee et al., 1996; Wolfe et al., 1996) and assertive communication skills (Hammond & Yung, 1991; Wolfe et al., 1996), is equally significant. Some research recorded visits to violence-related service providers (school counselors, crisis lines, support groups; (Foshee et al., 1996) in addition to unofficial reports (Jaffe et al., 1992). Other studies recorded the usage of peers as support personnel

(Shorey, R. C., Cornelius, T. L., & Bell, K. M., 2008) states that stable couples experienced the greatest levels of love and the least amount of conflict, as well as less frequent and milder instances of physical and emotional abuse. Longer relationship participation and more self-esteem were reported by this subgroup. Compared to secure lovers, stable minimizers reported moderate levels of love and conflict, low levels of emotional and physical abuse, and a greater propensity to employ avoidance and denial as coping mechanisms. On the other hand, hostile pursuers expressed considerable ambivalence over the relationship in addition to the highest degree of emotional abuse and moderate degrees of physical abuse. Last but not least, the hostile-disengaged group expressed the highest levels of conflict, the shortest relationship duration, the lowest reported love, and the most severe and frequent use of physical violence. While studying dating violence via a typological lens is a helpful beginning step in comprehending and treating dating violence, the amount of research on this topic is minimal.

It was not repeated on additional samples of violent dating couples, nor did it look at characteristics specific to male and female offenders. Although this study offers guidance for more research, the results should be regarded as preliminary and inconclusive for the time being.

Severe aggression rates are less frequently documented in the literature, but according to (Shorey, R. C., Stuart, G. L., & Cornelius, T. L., 2011) 8–16% of people in college dating relationships are thought to have experienced at least one act of severe physical aggression (such as punching, choking, or kicking a partner), 12–30% experience severe psychological aggression (such as threatening to hit a partner or destroy personal belongings), and 3–9% experience severe sexual aggression (such as using force or making threats to have sex with a partner) annually (Bell & Naugle, 2007; Hines & Saudino, 2003). Males and females perpetrate and experience similar levels of aggressiveness, regardless of the degree of the behavior, according to prevalence rates for dating couples (Prospero, 2007; Shorey et al., 2008)

Although studies have shown that using technology can have advantages, there are also serious drawbacks, according to (Baker, C. K., & Carreño, P. K., 2016) recent research, for instance, has revealed that teenagers harass and abuse people online, including their romantic partners. Still up for debate, though, are the ways in which dating violence and technology use interact at various phases of a couple's relationship and if this interaction differs for men and women. This article begins to fill these gaps by reporting the findings from focus groups with 39 high school aged youths, all of whom had experienced a difficult relationship in the last year. Findings indicated that teenagers frequently used text messages or posts to social networking sites to start and end dating relationships. Technology was utilized to monitor and keep spouses apart from others, which led to envy as well. The ways that technology is used differently by gender are highlighted. Lastly, suggestions for parent and adolescent preventative programmes are covered.

The relative contributions of five sets of characteristics—past violent experiences, attitudes, personality factors, relationship type, and socioeconomic status—to the occurrence of dating violence were examined, according to (Deal, J. E., & Wampler, K. S., 1986) 47% of the participants reported having encountered violence in a romantic relationship at some point. Most of these encounters were of a reciprocal character, with both parties acting violently occasionally. Males were three times more likely than females to report victim-only encounters when the violence was non-reciprocal. The primary predictor of violent experiences in current relationships, according to multiple regression analysis, is violent experiences in past relationships.

The most significant result in (O’Keefe M., 2005) that non-sexual violence in romantic relationships is equally committed by men and women. Research also reveals that women are more negatively impacted by aggression against them, particularly when it comes to bodily harm. Risk factors that have been found in the research literature to be associated with dating violence are discussed. These include past experiences with violence, views that violence is acceptable, peer pressure, and the presence of other problematic behaviors like drug use and engaging in risky sexual activities. Future study directions are indicated, including examining the experiences of dating violence among adolescents who identify as gay, lesbian, or bisexual.

(Simons, R. L., Lin, K. H., & Gordon, L. C., 1998) found a link between teenage drug use and delinquency and inadequate parental support and involvement. Drug abuse and delinquency in turn suggested a tendency towards dating violence. This aligns with previous research indicating that males who abuse their spouses frequently have a history of involvement in several criminal offenses (Fagan et al., 1983; Stacy & Shupe, 1983; Simons et al., 1995, 1997; Walker, 1979). Therefore, it would seem that both marital abuse and dating violence are frequently components of a broader antisocial disposition.

A systematic study titled (Taquette, S. R., & Monteiro, D. L. M., 2019). examined 35 publications, of which 71.4% were created in the United States. According to certain research, the prevalence is higher than 50% in both genders for both perpetrators and victims, with more dire outcomes for women. The research revealed three primary thematic cores: health issues linked to ADV, violence's circularity, and vulnerabilities related to ADV. Data show that ADV is more common in relationships with racism, heterosexism, and poverty and is ingrained in the patriarchal culture. It happens in a circle and is connected to other types of violence in various settings, including the home, community, school, and social media. It is linked to health issues like anxiety, depression, low self-esteem, and drug and alcohol abuse and abusive sex.

(Banyard, V. L., & Cross, C., 2008) found that there was a correlation between dating violence and worse scholastic outcomes, suicidal ideation, and greater levels of depression. Victimization and outcomes have a convoluted link due to alcohol use and despair. Examining sex variations in perceived social support patterns as a moderator, it was found that girls showed stronger impacts.

The study, (Olcay, T. ?. R. E., & YE??LTEPE) discovered that male students had far more benevolent sexist attitudes (74.93±22.41) than female students (60.14±22.02). This outcome aligns with the findings published by (Günes., 2020; Alptekin, 2014 & Koçyi?it and Me?e, 2020).

Male participants in all three research, which involved university students, reported more ambivalent sexism attitudes than female participants. According to (Koçyi?it & Me?e, 2020), the findings indicate that female students exhibit more egalitarian ideas regarding gender roles, whereas male students tend to have more sexist attitudes. Sexism is rooted in gender. In the process of socialization, gender helps people to develop their male and female identities and learn social roles and stereotypes (independent-dependent, rational-emotional, etc.) associated with those identities. Women are thus discriminated against and seen as inferior to men as a result of negative preconceptions that are placed on them.

Gender substantially impacted attitudes towards psychological, physical, and sexual dating violence, according to the study (Özge, Ü. N. A. L., Vargün, G. E., & Akgün, S., 2022) stated that as a result, and in partial agreement with earlier findings, the male participants developed affirmative attitudes towards all three forms of dating violence more than their female counterparts. In their investigation, (Anderson et al.,2011) demonstrated that the attitudes of the male and female participants varied not with regard to male-perpetrated sexual and physical violence but rather with regard to psychological dating violence, with a greater prevalence of affirmative attitudes among the males.

Making men more adept at spotting sexism will go a long way towards motivating men to become allies, claims (Drury, B. J., & Kaiser, C. R.,2014) that it is essential to change men's perceptions regarding the frequency and characteristics of subtle sexism, given the specific uncertainty surrounding this type of discrimination. Teaching men the legitimacy of their advantageous status in society can be crucial. More men will probably come to acknowledge sexism if they are encouraged to reject views that legitimise status (Swim et al., 2001; Swim et al., 2004; & Hyers/, 2007) and understand the damaging and ubiquitous character of sexism (Becker & Swim, 2012). Men should consider their privileged status in society as one method of approaching this issue (Case, Hensley, & Anderson., 2014). Men's support for contemporary forms of sexism decreased after participating in an intervention where they were asked to write thoughtfully about privilege and watch a video featuring men discussing how privilege improved their lives. When these interventions are coupled with initiatives to make males more aware of the possible risks associated with admitting sexism, they may prove to be very successful. Many men find it frightening to acknowledge the system's illegitimacy; therefore, self-affirmation inductions can be used to reduce this threat and make them more receptive to the message that sexism still presents widespread obstacles for women (Kahn, Barreto, Kaiser, & Rego., 2014).

The AWS and the (Swim et al.,1995) Modem Sexism and (Tougas et al., 1995) Neo-Sexism scales measure issues similar to the AWS, but in a more subtle way that reflects the greater egalitarianism towards women that has occurred in recent decades, according to "The Ambivalent Sexism Inventory: Differentiating Hostile and Benevolent Sexism." The idea that the attitudes the Modern Sexism scale draws upon do indeed show animosity towards women is supported by our discovery that HS has a substantial correlation with the scale whereas BS does not. Although there is a significant link between the HS scale and the Modem Sexism scale (which is likely also the case with Neo-Sexism), we think that the HS scale enhances rather than replaces these other measures. Remember that in our exploratory analysis, Recognition of Discrimination (questions that tapped into the same underlying concerns found in the Modem Sexism and Neo-Sexism scales) emerged as a distinct factor. Both HS and BS place greater emphasis on the interpersonal connections between men and women than on broad political positions, despite the fact that HS does examine relevant concerns (such as antifeminism). Therefore, the ASI may be especially relevant in the area of interpersonal relationships (e.g., heterosexual romantic relationships, one-on-one stereotyping, sexual harassment), while the Modem Sexism and Neo-Sexism scales may be more predictive for investigating gender-related political attitudes.

According to (Swim, J. K., Aikin, K. J., Hall, W. S., & Hunter, B. A., 1995).Higher levels of racism and sexism were linked to endorsement of individualistic views and non-endorsement of egalitarian attitudes. Depending on the respondents' sex and whether the prejudice scales measured contemporary or traditional ideas, these associations varied in strength. For both traditional and contemporary prejudices, racism and sexism were more closely associated with egalitarianism for women than with individualism. The fact that the factor analysis results indicate that there is less of a difference between old-fashioned and modern prejudices for women than for males may be the reason for the lack of unique patterns of correlations between old-fashioned and modern views for women. Protestant-Work-Ethic of Old-Fashioned Racism and Old-Fashioned Sexism was less predictive of men than Humanitarian-Egalitarian values; nevertheless, both values were strongly and equally connected with Modern Racism and Modern Sexism. This pattern indicates that individualistic principles are more significant in modern prejudice than they are in traditional prejudice.

(Dardenne, B., Dumont, M., & Bollier, T., 2007). states that participants were not more motivated to get the job under hostile circumstances as opposed to those under neutral or benign sexism. proving that, contrary to Experiment 1, responding well to hostile sexism was not a motivated act of retaliation. Moreover, participants perceived the situation as more negative when hostile and benign sexism was present compared to when it wasn't there. Crucially, Experiment 1 revealed that even while women did not specifically recognise benign sexism as sexism, they nevertheless thought it was just as repulsive as aggressive sexism.

That is, women were not indifferent to the expression of benevolent sexism, even if they did not recognise it as such. Women performed worse when confronted with benignant sexism than when confronted with aggressive sexism. This outcome could not be explained by women feeling more motivated to act out of retaliation or anger as a result of hostile sexism. In fact, motivation to land the job was the same in all three circumstances, despite the fact that performance improved when confronted with hostile rather than benign sexist attitudes. Therefore, we suggested that two major factors—first, the implicit sexism that communicates the idea that women lack ability, and second, the difficulty of assigning external meanings to these claims—would be accountable for women's lower performance (i.e., blaming the recruiter).

III. METHOD

A. Research Design

The current study applied descriptive research design to examine Dating Violence and Resilience among College students who are in a relationship. The basis of the quantitative techniques of current research is the collection and analysis of numerical data via Google Forms surveys, and tests.

B. Statement of the Problem

The present study focuses on the relationship among two variables, Dating Violence and Resilience.This study also examines the gender difference in the levels of Dating violence.

C. Objectives

- To investigate the relationship between dating violence and resilience among young adults.

- To examine the differences among gender in prevalence of Dating violence experienced within romantic relationships among young adults.

- To examine the differences among gender in resilience within romantic relationships among young adults.

- To investigate the difference in dating violence amongst undergraduate and postgraduate students

- To investigate the difference in resilience of undergraduate and postgraduate students

D. Hypothesis

H01- There is a significant relationship between Dating violence and Resilience among young adults.

H02- There is no significant gender difference in Dating violence among young adults.

H03-There is no significant gender difference in Resilience among young adults.

H04:There is no significant difference in dating violence amongst undergraduate and postgraduate students

H05:There is no significant difference in resilience of undergraduate and postgraduate students

E. Operational Definition

- Dating Violence

Dating violence, also known as courtship violence and premarital abuse, was defined by the National Centre for Injury Prevention and Control (1997) as the "perpetration or threat of an act of violence by at least one member of an unmarried couple on the other member within the context of dating or courtship." All forms of physical violence, verbal and emotional abuse, and sexual assault are included in this category of violence.

2. Resilience

Resilience is a term used to characterise people who show strength and adaptation in the face of adversity. It also implies emotional fortitude. In 1990, Wagnild and Young The ability to adjust and bounce back from trying or stressful situations in life is known as resilience. It is the ability to overcome hardship, trauma, or stress and carry on with daily activities on a physical and mental level.

3. Variables

a. Dating Violence

b. Resilience

4. Demographic Details

a. Age

b. Gender

c.Level of education

5. Population

College students who are pursuing Undergraduate and postgraduate courses are the population of current study.

6. Sample and Technique

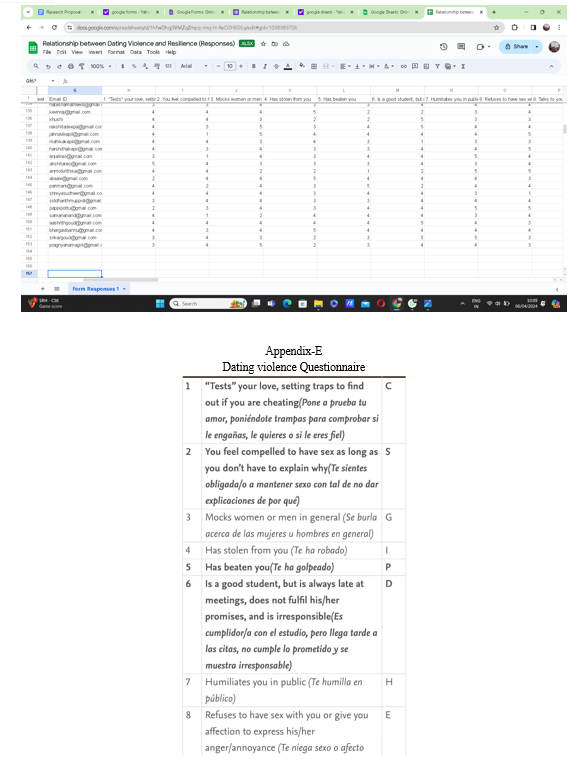

A sample of 200 students will be taken for the study, the information will be collected in online mode by circulating the google form. Non-probable and convenient sampling will be used in the research.

F. Tools for the Study

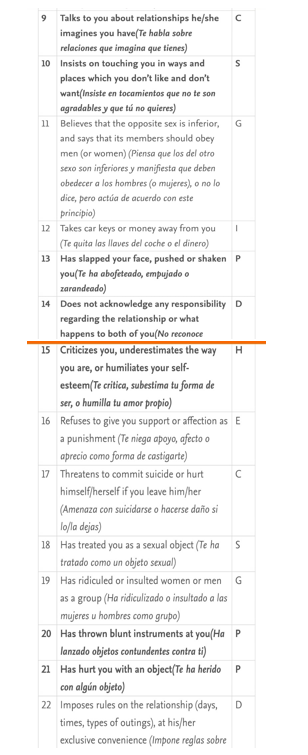

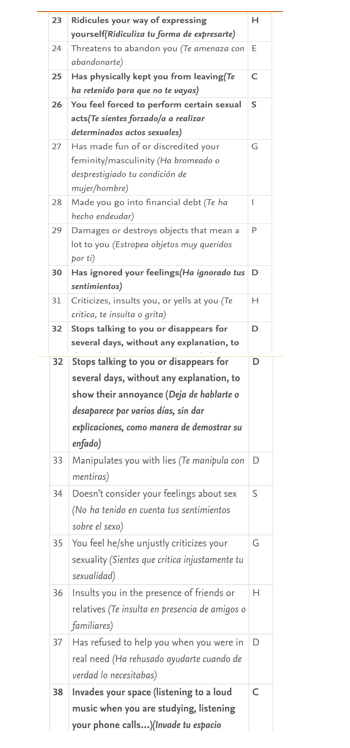

- Dating Violence Questionnaire

The study will incorporate the original Dating Violence Questionnaire, as developed by Rodriguez-Franco et al. (2010). Using a 5-point Likert scale (from 0-never to 4-all the time), it measures 42 distinct types of abuses that may occur in intimate relationships and provides information regarding perceived victimization frequency and disturbance. Eight categories of abuse are included in its measurement of dating violence: physical, emotional, coercive, sexual, humiliating, gender-based, and instrumental. Despite the fact that the initial survey offers a way to gauge felt victimization (frequency) as well as perceived disturbance. The victimization scores' frequency is the only source of data used in this study. It has been discovered that the DVQ is a legitimate and trustworthy instrument for measuring the many types of violence that can transpire in a relationship. The validity of the DVQ-8 version as a screening tool in educational contexts has been established. To provide additional measures, including the Dating Abuse Perpetration Acts Scale (DAPAS), the DVQ has been updated. All things considered, the DVQ is a helpful instrument for evaluating dating violence victimization and perpetration, and multiple research have attested to its validity and reliability.

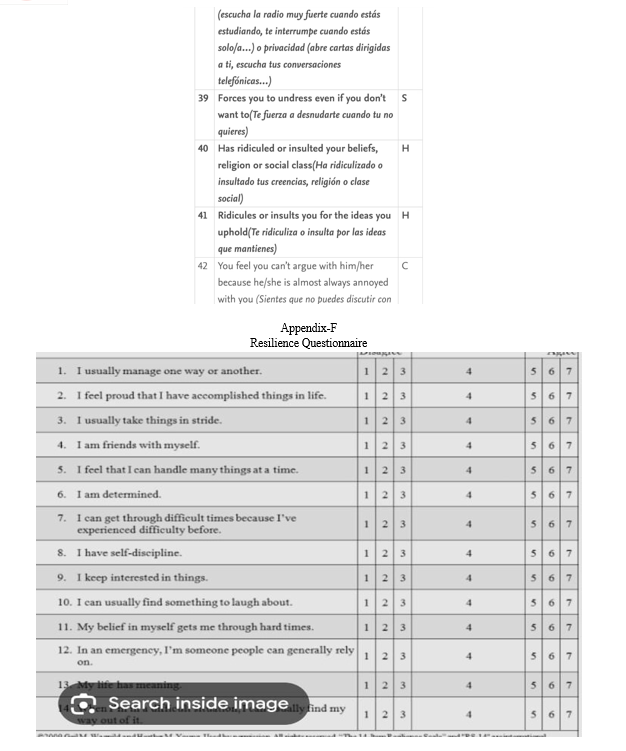

2. 14-Item Resilience Scale (RS-14)

The Young 14- Item Resilience Scale (RS-14) was developed by Gail M. Wagnild and Heather M. Young, 1990 to determine the degree of individual psychological resilience. The scale consists of 14 items. The responses are elicited on a 7-Likert point scale ranging from 1 (disagree) to 7 (agree). All the items are positively scored, and the minimum score on the 14-item scale is 14 and the maximum score is 98. Wagnild has shown that a score <56 indicates a very low resilience level; a score between 57 and 64 indicates a low resilience level; a score between 65 and 73 indicates that resilience level is on the low end; a score between 74 and 81 indicates a moderate resilience level; a score between 82 and 90 indicates a moderately high resilience level; and a score >91 indicates a high resilience level (Wagnild & Young, 1990).

3. Rationale

The rationale for this research is to raise awareness about the issue of teen dating violence and to identify the factors that contribute to it. By understanding the predictors of teen dating violence and victimization, researchers and policymakers can develop effective prevention and intervention strategies to address this serious social problem

4. Research Gap

Although there are various research papers exploring on the current variables, to the best of the researcher’s knowledge, the relationship has not ben studied extensively with the current population and geographical location

5. Purpose of the Study

The purpose of the study is to identify the factors associated with teen dating violence and victimization. The study aims to explore the relationship between personal adjustment, clinical maladjustment, and resilience with teen dating violence and victimization. The study will use a cross-sectional survey design and a stratified random sampling method teenagers aged 18-24 years old who are currently in a dating relationship. The study will use reliable and valid standardized tools to collect data. The results of the study can help identify risk factors for teen dating violence and inform the development of prevention and intervention programs.

6. Statement of the Problem

This research design aims to investigate the factors associated with dating violence and victimization. The standardized tools that will be used are reliable and valid measures of teen dating violence, sexism, clinical maladjustment, and resilience. The results of this study can help identify risk factors for teen dating violence and inform the development of prevention and intervention programs.

G. Inclusion and Exclusion criteria

- Inclusion Criteria

The participant should be at least 18 years old to participate in the study.

Participants should be in a heterosexual relationship

2. Exclusion Criteria

The participant should be in a relationship for at least 6 months

H. Ethical Considerations

The following ethical considerations have been taken into account:

- Informed Consent: Participants have been informed about the nature and purpose of the study, and their rights as participants. All participants have been provided with an informed consent form, which outlines the voluntary nature of their participation and their right to withdraw at any time without penalty.

- Confidentiality and Privacy: Participants' confidentiality and privacy have been protected. All data collected have been kept anonymous and confidential, and the data has been stored securely to prevent unauthorized access..

- Risk Assessment: The study has not posed any physical or psychological harm to the participants. There were no identified risks associated with this study.

- Fair Selection of Participants: Participants have been selected fairly without any bias or discrimination based on any characteristic such as race, gender, ethnicity, or socioeconomic status.

- Debriefing: At the end of the study, participants have been debriefed and provided information about the purpose of the study and their contributions to the research.

IV. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

A. Results

The aim of this research was to study Dating Violence and Resilience among Young Adults. The study was conducted on 150 students. The sample was collected from students from both Undergraduates and Postgraduates. Sample was collected through a google form with informed consent of individuals.

Table-1: Shows the descriptive statistics of the sample

|

Baseline Characteristics |

Dating Violence |

Resilience |

|

|

|

n % |

n % |

|

|

Age |

|

|

|

|

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

Gender

Male

Female

|

15 9.6%

20 12.8%

23 14.7%

16 10.3%

57 36.5%

13 8.3%

5 3.2%

4 2.6%

70 43.6%

83 53.8% |

15 9.6%

20 12.8%

23 14.7%

16 10.3%

57 36.5%

13 8.3%

5 3.2%

4 2.6%

70 43.6%

83 53.8% |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Current Education level |

|

|

|

|

Twelth

Undergraduation

Post Graduation |

4 2.6%

62 39.7%

90 57.7% |

4 2.6%

62 39.7%

90 57.7% |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Table- 2: Relationship between Dating violence and Resilience among young adults.

|

Variables |

M |

SD |

r Sig. |

|

Dating violence |

108.80 |

47.38 |

-0.22 .051 |

|

Resilience |

70.30 |

14.80 |

|

Table 2 shows the correlation between Dating violence and Resilience among young adults. The mean and standard deviation of the Dating violence is found to be 108.80 and 47.38. In Resilience the mean and standard deviation was found to be 70.30 and 14.80. The correlation between Dating violence and Resilience was found to be .181. There is a negative correlation between Dating violence and Resilience. The alternative hypothesis o f there is a significant relationship between Dating violence and Resilience among Young adults was hence accepted.

Table-3: Showing the Mann-Whitney-U Test results for difference in Dating violence among males and females

|

|

Male |

|

|

Female |

|

|

||

|

|

Mean |

SD |

Mean Rank |

Mean |

SD |

Mean Rank |

Z |

Sig.value |

|

Dating violence |

118.14 |

44.70 |

68.20 |

97.11 |

44.20 |

65.21 |

-.45 |

.65 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Table 3 shows Mann Whitney’s U value, mean rank, sum of ranks and median of Dating violence The mean value for dating violence in male is 118.14 and the Standard deviation was found to be 44.70. The mean value for dating violence in female is 97.11and the Standard deviation was found to be 44.20. Hence the null hypothesis stating that there is no significant difference in Dating violence among males and females is accepted .

Table-4: -Showing the Mann-Whitney-U Test results for difference in Resilience among males and females

|

|

Male |

|

|

Female |

|

|

||

|

|

Mean |

SD |

Mean Rank |

Mean |

SD |

Mean Rank |

Z |

Sig.value |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Resilience |

70.10 |

15.04 |

63.11 |

70.37 |

14.42 |

69.08 |

-.89 |

.37 |

Table 4 shows Mann Whitney’s U value, mean rank, sum of ranks and median of Resilience. The mean value for Resilience in male is 70.10 and the Standard deviation was found to be 15.04. The mean value for Resilience in female is 69.08 and the Standard deviation was found to be 14.42. Hence the null hypothesis stating that there is no significant difference in Resilience between males and females is accepted

Table-5: Showing the difference in dating violence amongst undergraduate and postgraduate students

|

|

Undergraduates |

|

|

Postgraduates |

|

|

||

|

|

Mean |

SD |

Mean Rank |

Mean |

SD |

Mean Rank |

Z |

Sig.value |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Dating violence |

63.01 |

46.60 |

87.95 |

106.25 |

49.50 |

67.44 |

-2.84 |

0.004 |

Table 5 shows Mann Whitney’s U value, mean rank, sum of ranks and median of Dating Violence for undergraduate and postgraduate students.. The mean value for Undergraduates is 63.01, the mean rank is 87.95 and the Standard deviation was found to be 46.60. The mean value for Dating violence in postgraduates is 106.25, the mean rank is 67.44 and the Standard deviation was found to be 49.50. Hence the null hypothesis stating that there is no significant difference in Dating violence among undergraduates and postgraduates is accepted

Table-6: Showing the difference in Resilience amongst undergraduate and postgraduate students

|

|

Undergraduates |

|

|

Postgraduates |

|

|

||

|

|

Mean |

SD |

Mean Rank |

Mean |

SD |

Mean Rank |

Z |

Sig.value |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Resilience |

70.10 |

14.73 |

76.57 |

90.05 |

49.50 |

75.54 |

-.136 |

0.08 |

Table 6 shows Mann Whitney’s U value, mean rank, sum of ranks and median of Resilience. The mean value for Resilience in Undergraduates is 14.73 and the Standard deviation was found to be 76.57. The mean value for Resilience in postgraduates is 90.05, the mean rank is 75.54 and the Standard deviation was found to be 49.50. Hence the null hypothesis stating that there is no significant difference in Resilience amongst undergraduate and postgraduate students is accepted

The purpose of the study was to investigate the relationship between Dating violence and Resilience in young adults. The study was conducted on a sample size of 151 students. Table 2 shows the correlation between Dating violence and Resilience among young adults. The mean and standard deviation of the Dating violence is found to be 108.80 and 47.375. In Resilience the mean and standard deviation was found to be 70.30 and 14.80. The correlation between Dating violence and Resilience was found to be .181. There is a negative correlation between Dating violence and Resilience. The alternative hypothesis, “there is a significant relationship between Dating violence and Resilience among Young adults” was hence accepted.

The findings from the data collected show that there is a positive correlation between Dating Violence and Resilience. Table 3 shows Mann Whitney’s U value, mean rank, sum of ranks and median of Dating violence.. The mean value for dating violence in male is 118.14 and the Standard deviation was found to be 44.70. The mean value for dating violence in females is 97.11and the Standard deviation was found to be 44.20. Hence the null hypothesis stating that there is no significant difference in Dating violence between males and females is accepted . These findings align with the previous studies conducted. This implies that the increase in Dating Violence affects the Resilience in individuals. Table 4 shows Mann Whitney’s U value, mean rank, sum of ranks and median of Resilience. The mean value for Resilience in male is 70.10 and the Standard deviation was found to be 15.04. The mean value for Resilience in females is 69.08 and the Standard deviation was found to be 14.42. Hence the null hypothesis stating that there is no significant difference in Dating violence and Resilience between males and females is accepted. Table 5 shows Mann Whitney’s U value, mean rank, sum of ranks and median of Dating Violence for undergraduate and postgraduate students.. The mean value for Undergraduates is 63.01, the mean rank is 87.95 and the Standard deviation was found to be 46.60. The mean value for Dating violence in postgraduates is 106.25, the mean rank is 67.44 and the Standard deviation was found to be 49.50. Hence the null hypothesis stating that there is no significant difference in Dating violence among undergraduates and postgraduates is accepted. Table 6 shows Mann Whitney’s U value, mean rank, sum of ranks and median of Resilience. The mean value for Resilience in Undergraduates is 14.73 and the Standard deviation was found to be 76.57. The mean value for Resilience in postgraduates is 90.05, the mean rank is 75.54 and the Standard deviation was found to be 49.50. Hence the null hypothesis stating that there is no significant difference in Dating violence and Resilience between males and females is accepted

There is a significant rise in the Indian population and suggests that 20% - 40% of college going students are at risk for Dating Violence . (Jenkins, H. B.,2017). New York Times article by Matt Richtelel published in (2021) stated lifestyle can have an influence on Resilience among individuals. The alarming Increase in the levels of Dating Violence is now concerning many young adults. This study examined how the increased Dating violence to Resilience is causing an increased impact on the daily functioning of individuals.

Considering the data results from the current study show how it is going to impact the college students in their academics and social functioning. . A study conducted by (Swim, J. K., & Cohen, L. L.,1997). Overt, covert, and subtle sexism: A comparison between the attitudes toward women and modern sexism scales. (Dardenne, B., Dumont,M., & Bollier,T.,2007) Insidious dangers of benevolent sexism:consequences for women’s performance show that the students who lived away from their hometown for the semester showed higher dating violence than the students who stayed with their parents. The current study shows that there is no significant difference between male and female population in Dating violence and Resilience. Findings also showed that there is no significant difference between the genders in the levels of Dating violence while some studies also showed a similar finding. Research revealed that there was a significant interdependence of Dating violence and Resilience as a mediating factor among college students. The studies prove that these two variables are interconnected and change in Dating violence can cause change in Resilience.

V. ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

I, KRISHNAMURTHY SRI VIDYA (22MPLB27) OF MSc. Clinical Psychology, submit my dissertation on “Relationship between Dating Violence and Resilience among young adults''. I would like to thank the almighty for always being the strength throughout this journey. I express my gratitude to the college and the management for giving me this opportunity. I would like to thank Dr. Sruthi Sivaraman, Head of the Department of Psychology for the constant support for my research. I would like to express my gratitude and sincere thanks to my research supervisor, Dr. Sruthi Sivaraman, Head Department of Psychology for her guidance and support throughout. I would like to thank all the professors of the department and to my family members and friends for their constant support and strength.

Conclusion

A. Summary The study aimed at studying Dating violence and Resilience in students. The research question was; Is there a relationship between Dating violence and Resilience in students? And find the difference between male and female population in levels of Dating violence and Resilience. A total of 151 data was collected consisting of males, females of undergraduates and post graduates. The Hypothesis for the study were as follows: H1- There is a significant relationship between Dating violence and Resilience among young adults H2- There is no significant gender difference in Dating violence among young adults.H3-There is no significant gender difference in Resilience among young adults.H4:There is no significant difference in dating violence amongst undergraduate and postgraduate students H5:There is no significant difference in resilience of undergraduate and postgraduate students. The data was collected with consent of the participants and scored according to the manuals of the scales. Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) is used for the analysis of data. Spearman correlation was used for the study to check if there is a relationship between Dating violence and Resilience. Additionally Mann Whiteney\'s U-test was used to check if there is any gender difference in Dating violence. B. Conclusion The goal of the study was to study the relationship between Dating violence and Resilience while also studying if there is a difference in the genders in levels of Dating violence and Resilience. The results showed a significant relationship between the variables. It showed a positive relationship which means that if one increases then the other increases. This means that gender does not plays a role with regard to the involvement of Dating violence and Resilience. This study showed how an increase in one variable ie.Dating violence can cause a significant change by increase in Resilience. The study showed a significant positive relationship between the variables and there is no difference in the female and male population in the levels of Dating violence. There is no significant difference in Dating violence and Resilience between males and females.There is no significant difference in Dating violence and Resilience between males and females. There is no significant difference in Dating violence among undergraduates and postgraduates. There is no significant difference in Resilience amongst undergraduate and postgraduate students C. Implications This study contributes to the betterment of the student population. Studying a link Dating violence and Resilience helps to clarify the possible harm that excessive activity may do to one’s Resilience. The findings suggest the importance of incorporating resilience into therapeutic interventions for individuals who have experienced dating violence. Therapists could focus on enhancing coping mechanisms, self-esteem, and social support networks to bolster resilience in survivors. Education and prevention programs should emphasize the cultivation of resilience skills among adolescents and young adults to mitigate the negative impact of dating violence. These programs could include components on healthy relationship dynamics, conflict resolution strategies, and emotional regulation techniques. Policymakers and advocates can use this information to advocate for policies and initiatives aimed at reducing dating violence and promoting resilience-building resources within schools, communities, and healthcare settings. This could involve allocating resources for counseling services, support groups, and educational campaigns Further research is warranted to explore the specific mechanisms through which resilience buffers the effects of dating violence. Longitudinal studies could elucidate the long-term implications of resilience on mental health outcomes and relationship quality. Additionally, evaluating the effectiveness of resilience-focused interventions could guide future practice and policy efforts. It\'s important to consider how factors such as gender, race, sexual orientation, and socioeconomic status intersect with experiences of dating violence and resilience. Tailoring interventions to address the unique needs of diverse populations is essential for promoting inclusivity and effectiveness. Overall, recognizing the relationship between dating violence and resilience underscores the importance of comprehensive, strengths-based approaches to support survivors and prevent future victimization.

References

[1] Ak??, N., Korkmaz, N.H., Taneri, P.E., Özkaya, G., and Güney, E. (2019). Üniversite ö?rencilerinde flört ?iddeti sikli?i ve etkileyen etmenler. Eski?ehir Türk Dünyas? Uygulama ve Ara?t?rma Merkezi Halk Sa?l??? Dergisi, (3), 294-300. [2] Alptekin, D. (2014). Çeli?ik duygularda toplumsal cinsiyet ayr?mc?l??? sorgusu: üniversite gençli?inin cinsiyet alg?s?na dair bir ara?t?rma. Selçuk Üniversitesi Sosyal Bilimler Enstitüsü Dergisi, 32, 203-211. [3] Aslan, D., Vefikulucay, D., Zeynelo?lu, S., Erdost, T., and Temel, F. (2008). Ankara’da iki hem?irelik yüksekokulu’nun birinci ve dördüncü s?n?flar?nda okuyan ö?rencilerin flört ?iddetine maruz kalma, flört ili?kilerinde ?iddet uygulama durumlar?n?n ve bu konudaki görü?lerinin saptanmas? ara?t?rmas?. Ankara: Hacettepe Üniversitesi Kad?n Sorunlar? Ara?t?rma ve Uygulama Merkezi. [4] Aslan, R., Bulut, M., and Arslanta?, H. (2020). Flört ?iddeti. The Journal of Social Science, 7(45), 365-384. [5] Av?ar, B.G., and Ak??, N. (2017). Flört ?iddeti. Uluda? Üniversitesi T?p Fakültesi Dergisi, 43(1), 41-44. [6] Ayan, S. (2014). Cinsiyetçilik: Çeli?ik duygulu cinsiyetçilik. Cumhuriyet T?p Dergisi, 36, 147-156. [7] Ayral, S. (2021). Flört ?iddetine yönelik tutumlar?n çeli?ik duygulu cinsiyetçilik ile ?iddetin ve erkek egemenli?inin me?rula?t?r?lmas? aç?s?ndan incelenmesi. (Yay?mlanmam?? yüksek lisans tezi). Ufuk Üniversitesi Sosyal Blimler Enstitüsü Psikloloji Anabilim Dal?, Ankara. [8] Ayy?ld?z, A.B., and Taylan, H.H. (2018). Üniversite ö?rencilerinde flört ?iddeti tutumlar?: Sakarya Üniversitesi Örne?i. Akademik Sosyal Ara?t?rmalar Dergisi, 6(8), 413-427. [9] Bal, T.E. (2018). Erkek sporcularda sporcu kimli?inin çeli?ik duygulu cinsiyetçilik ile ili?kisinin incelenmesi. (Yay?mlanmam?? doktora tezi). Akdeniz universitesi Sa?l?k Bilimleri Enstitüsü Hareket ve Antrenman Anabilim Dal?, Antalya. [10] Bell, K.M.; Naugle, A.E. Intimate partner violence theoretical considerations: Moving towards a contextual framework. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2008, 28, 096–1107. [11] Billingham, R. (1987). Courtship violence: The patterns of conflict resolution strategies across seven levels of emotional commitment. Family Relations, 36, 283?28 [12] Calderon, M. Violencia Política y Elecciones Municipales en Michoacán; Instituto Mora-ColMich: Michoacan, Mexico, 1994. [13] Carlson, B. E. (1987). Dating violence: A research review and comparison with spousal abuse. Social Casework: The Journal of Contemporary Social Work, 68, 16?23 [14] Connor, K. M., & Davidson, J. R. T. (2003). Development of a new resilience scale: The Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC). Depression and Anxiety, 18, 76–82. [15] Cornelius, T. L., & Resseguie, N. (2007). Primary and secondary prevention programs for dating violence: A review of the literature. Aggression and violent behavior, 12(3), 364-375. [16] Drury, B. J., & Kaiser, C. R. (2014). Allies against sexism: The role of men in confronting sexism. Journal of social issues, 70(4), 637-652 [17] Herrman, H. D. E., Stewart, M. D. Diaz-Granados, N., Berger, E. L., Jackson, B., & Yuen, T. (2011). What is resilience? Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 56, 258–265 [18] Jackson, S. M. (1999). Issues in the dating violence literature: A review of the literature. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 4(2), 233?247. [19] Jackson, S. M., Cram, F., & Seymour, F. (2000). Violence and sexual coercion in high school students\' dating relationships. Journal of Family Violence, 15(1), 23?36 [20] Jackson, S.; Cram, F.; Seymour, F. Violence and sexual coercion in high school students’ dating relationships. J. Fam. Violence 2000, 15, 23–36. [21] Jezl, D. R., Molidor, C. E., & Wright, T. L. (1996). Physical, sexual and psychological abuse in high school dating relationships: Prevalence rates and self-esteem issues. Child & Adolescent Social Work Journal, 13(1), 69?87 [22] Lane, K., & Gwartney-Gibbs, P. (1985). Violence in the context of dating and sex. Journal of Family Issues, 6, 45?56 [23] Lavoie, F., Vezina, L., Piche, C., & Boivin, M. (1995). Evaluation of a prevention program for violence in teen dating relationships. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 10, 516?524 [24] Lewis, S. F., & Fremouw, W. (2001). Dating violence: A critical review of the literature. Clinical Psychology Review, 21(1), 105?127. [25] Lo, W. A., & Sporakowski, M. J. (1989). The continuation of violent dating relationships among college students. Journal of College Student Development, 30, 432?439. [26] Martínez, I.; Murgui, S.; García, O.F.; García, F. Parenting in the digital era: Protective and risk parenting styles for traditional bullying and cyberbullying victimization. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2019, 90, 84–92. [27] Moreno-Ruiz, D.; Estevez, E.; Jimenez, T.I.; Murgui, S. Parenting style and reactive and proactive adolescent violence: Evidence from Spain. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 2634. [28] Murray, A.; Azzinaro, I. Teen Dating Violence: Old Disease in a New World. Clin. Pediatr. Emerg. 2019, 20, 25–37. [29] Pazos Gomez, M.; Delgado, A.O.; Gómez, Á.H. Violencia en relaciones de pareja de jóvenes y adolescentes. Rev. Latinoam. Psicol. 2014, 46, 148–159. [30] Riggs, D.S.; O’Leary, K.D. Aggression between heterosexual dating partners: An examination of a causal model of courtship aggression. J. Interpers. Violence 1996, 11, 519–540. [31] Roscoe, B., & Kelsey, T. (1986). Dating violence among high school students. Psychology, A Quarterly Journal of Human Behavior, 23, 198?202 [32] Serran, G.; Firestone, P. Intimate partner homicide: A review of the male proprietariness and the self-defense theories. Aggress Violent Behav. 2004, 9, 1–15. [33] Smith, B. W., Dalen, J., Wiggins, K., Tooley, E., Christopher, P., & Bernard, J. (2008). The brief resilience scale: assessing the ability to bounce back. International journal of behavioral medicine, 15, 194-200. [34] Sugarman, D., & Hotaling, G. (1989). Dating violence: Prevalence, context, and risk markers. In M. Pirog-Good & J. Stets (Eds.), Violence and dating relationships (pp. 3?32). New York: Praeger. [35] Tharp, A.T.; McNaughton Reyes, H.L.; Foshee, V.; Swahn, M.H.; Hall, J.E.; Logan, J. Examining the Prevalence and Predictors of Injury from Adolescent Dating Violence. J. Aggress. Maltreat Trauma 2017, 26, 445–461. [36] Truman-Schram, D. M., Cann, A., Calhoun, L., & Vanwallendael, L. (2000). Leaving an abusive dating relationship: An investment model comparison of women who stay versus women who leave. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 19(2), 161?183. [37] Ulloa, E.C.; Kissee, J.; Castaneda, D.; Hokoda, A. A global examination of teen relationship violence. In Women’s Psychology. Violence against Girls and Women: International Perspectives: In Childhood, Adolescence, and Young Adulthood; In Adulthood, Midlife, and Older Age; Sigal, J.A., Denmark, F.L., Eds.; Praeger/ABC-CLIO: Santa Barbara, CA, USA, 2013; pp. 211–238. [38] Wolfe, D. A. (2006). Preventing violence in relationships: Psychological science addressing complex social issues. Canadian Psychology, 47, 44?50.

Copyright

Copyright © 2024 Krishnamurthy Sri Vidya , Dr. Sruthi Sivaraman . This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Download Paper

Paper Id : IJRASET61299

Publish Date : 2024-04-29

ISSN : 2321-9653

Publisher Name : IJRASET

DOI Link : Click Here

Submit Paper Online

Submit Paper Online