Ijraset Journal For Research in Applied Science and Engineering Technology

- Home / Ijraset

- On This Page

- Abstract

- Introduction

- Conclusion

- References

- Copyright

Social Acceptance of Vulnerable Groups of Students in the Peer Group

Authors: Danijela Jelisavac

DOI Link: https://doi.org/10.22214/ijraset.2024.64687

Certificate: View Certificate

Abstract

Prior studies have shown that socially accepted students tend to be more focused on learning and achieve better academic outcomes, and social acceptance plays a key role in students\' psychological well-being. Social acceptance among students significantly impacts their academic success. When students feel accepted and included in the school environment, they show greater motivation to learn and achieve better results. This highlights the importance of creating an inclusive school environment where every student feels welcome and supported. The research of social acceptance of vulnerable groups of students in the peer group was conducted using sociometry among fifth graders in Slovenia. We found out that most fifth-grade students fall into the group with an average sociometric status. Additionally, students from vulnerable groups predominantly have either medium or low sociometric status. However, the assumption that students from vulnerable groups would primarily fall into rejected or neglected sociometric categories was not confirmed, as they occupied various sociometric positions. Understanding the group with average sociometric status is essential for supporting social acceptance and improving academic achievement. Programs and interventions tailored to this group could help enhance their social skills and school integration. Further research is needed to promote social acceptance, foster collaboration between schools, parents, and education experts, and raise teachers\' awareness of the importance of social inclusion in the classroom. These efforts can contribute to a more inclusive school environment, benefiting students\' academic success and long-term well-being.

Introduction

I. INTRODUCTION

In modern society, increasing emphasis is placed on the inclusion and support of vulnerable groups of students in the school environment. These groups include students with special needs, immigrants, students with behavioural problems and students with learning difficulties. A key aspect of their success and well-being in and out of school is social acceptance. Socially accepted students feel safe, included and supported in their social environment, which positively affects their academic performance, psychological well-being and long-term social inclusion. During growing up and especially during elementary school, satisfactory peer relationships are very important, as they place children in front of new demands, and at the same time offer them new opportunities for social and emotional development (Gifford-Smith and Brownell, 2003).

Nevertheless, vulnerable groups of students often face challenges and difficulties in social acceptance. This may stem from prejudice, stereotypes, ignorance or improper treatment by peers and the entire school community. The consequences of social exclusion can lead to reduced self-esteem, depression, poor academic performance and problems in interpersonal relationships. Low peer acceptance is associated with a range of negative developmental outcomes, such as delinquency, grade repetition, psychological maladjustment, as well as lower school performance, which some authors attribute to negative peer experiences, which may be related to lower motivation for schoolwork and consequently with school failure (Buhs and Ladd, 2001). For these reasons, the study of social acceptance among vulnerable groups of students and the provision of assistance are particularly important already during elementary school.

Baydik and Bakkaloglu (2009) note that students with special needs are less accepted by their peers and more rejected than their peers without special needs; here, the most important factor of social rejection is the behavioural problems of students with special needs. According to the results of several studies, students with learning difficulties have fewer reciprocal friendships, lower quality friendships and lower social acceptance (Wiener and Schneider, 2002; Wiener and Tardif, 2004). Similarly, Kuhne and Wiener (2000) find that students with learning disabilities have a lower social preference and are more likely to take a rejected social position in the classroom. Stone and LaGreca (1990) find that students with learning disabilities are placed to a greater extent in the group of rejected and ignored students and to a lesser extent in the group of popular and average students, compared to students who learn they have no problems.

Research on a sample of Slovenian fourth graders in the 1995/96 school year also showed that students with learning difficulties are significantly worse integrated than their classmates, and their inadequate social inclusion is conditioned by characteristics such as poor school performance, social and interactional problems in the relationship to classmates and teachers, poor self-esteem (Schmidt, 2001). Peterka (2016) found that the majority of immigrant students belong to the rejected group. Mikli? (2013), however, states that immigrants most often occupy a lower or middle sociometric position in the class. A minority of research does not support the above findings; after reviewing several studies, Dudley-Marling and Edmiaston (1985) note that some students with learning difficulties are also placed in the group of popular students. Wiener, Harris and Shirer (1990) also note that not all children with learning difficulties are rejected; the results of their research show that half of the students with learning difficulties are placed in the group of students with an average sociometric position. Immigrant students may also occupy different sociometric statuses and groups within the class, or they may be socially accepted in different ways. Immigrant students may be less socially accepted, but not the most socially rejected in their class (Peterka, 2016). It depends on the individual student, how he knows how to connect, what his classmates are like, and time also affects this. Friendships need time to develop, and classmates need to get to know each other (Mikli?, 2013).

II. METHODOLOGY

A. Research Purpose

In the field of social acceptance of vulnerable groups of students, it is important to understand how the school environment can create and maintain an inclusive and supportive climate for all students. A thorough review of the factors that influence social acceptance and the study of the effectiveness of interventions to improve it is crucial in designing approaches that can increase the inclusion, support and well-being of vulnerable groups of students in the school environment. This can contribute to a fairer and more inclusive education, where every student can reach their full potential. The purpose of the present research is to determine the sociometric position of students from vulnerable groups, or how the mentioned group of students is accepted by the other students in the class. Previous research in this field has given inconsistent results, moreover, the vast majority were conducted abroad, and the results of these studies are difficult to generalize to the Slovenian educational system due to different criteria for awarding additional professional and other help, so we wanted to check the situation on a Slovenian sample of elementary school students.

B. Research Aim and Hypotheses

The aim of the research or task is to check the social acceptance of pupils from vulnerable groups within each section of fifth graders. More specifically, we will determine their sociometric status and the sociometric group they occupy within the class. Here we assume the following:

H1: Most students in each class belong to the group of students with an average sociometric position.

H2: Most students from vulnerable groups are in the group of rejected or ignored students in each class.

H3: Students from vulnerable groups have a low or medium sociometric status in each class.

C. Sample

A total of 82 students from three classes of the fifth grade of a randomly selected primary school are included in the research. The sample includes entire classes, including immigrant students, students with additional professional help, students with emotional or behavioural problems and students with learning difficulties.

D. Data Collection Procedures and Analysis

To obtain data on the sociometric position of the students, a sociometric test is used with a positive ("List three classmates with whom you like to hang out the most") and a negative criterion ("Name three classmates with whom you like to hang out the least"). According to the approach of standardized achievements by Coie, Dodge and Coppotelli (1982), based on the results of the sociometric test, we can determine measures of social preference or liking (difference between standardized positive and negative choices) and social influence or observability (sum of standardized positive and negative choices) of students in the group. The combination of the two measures (likeability and observability) allows students to be divided into five sociometric groups (Jackson and Bracken, 1998):

- Popular students with many positive and few or no negative choices, characterized by high social preference;

- Rejected students with many negative and few or no positive choices, characterized by low social preference;

- Ignored students with few or no choices, characterized by low social influence;

- Controversial students with many positive and many negative choices, characterized by high social influence;

- Average students with an average number of positive and negative choices.

A sociometric test was conducted in each of the mentioned classes. The data were collected in a primary school in the coastal-karst region. The data was collected by a school counsellor. The data were processed according to the previously mentioned two-dimensional sociometric classification system of Coie, Dodge and Coppotelli (1982). Information about which students are foreigners or receive additional professional help and have learning difficulties or emotional-behavioural problems we got from the school counsellors.

The sociometric status (SS) of each student was calculated based on the following formula:

Here, M is the average number of choices or choices that the student had available, and N is the number of test participants and:

- SS < 0.90 indicates low sociometric status,

- 0.90 < SS < 1.19 indicates medium sociometric status and

- 1, 19 < SS indicates a high sociometric status

III. RESULTS

Based on the number of positive and negative sociometric choices received, the students were placed into five sociometric groups. We used the classification procedure of Coie, Dodge and Coppotelli (1982). The procedure is based on the standardization of positive and negative sociometric choices and represents one of the most frequently used sociometric classifications. For a description of the procedure, see Pe?jak and Košir (2008). Standardization of positive and negative choices was carried out within individual classes.

A. Sociometry of the 5.a class

There are 28 students in 5.a, 15 girls (54%) and 13 boys (46%). In the class there are 2 (7%) foreign students (6 and 20), 2 (7%) students with behavioural problems (4 and 12) and 2 (7%) students with learning difficulties (14 and 17). In total, therefore, in the 5.a, 6 students (21%) belong to vulnerable groups of students.

TABLE I

Sociometric statuses of students from vulnerable groups in 5.a

|

Student ID |

SS |

|

4 |

1 |

|

6 |

1 |

|

12 |

1 |

|

14 |

0,89 |

|

17 |

0,93 |

|

20 |

1,07 |

From Table 1, we can see that only one student from the group of vulnerable students has a low sociometric status (0.89). The rest of the students have a medium sociometric status.

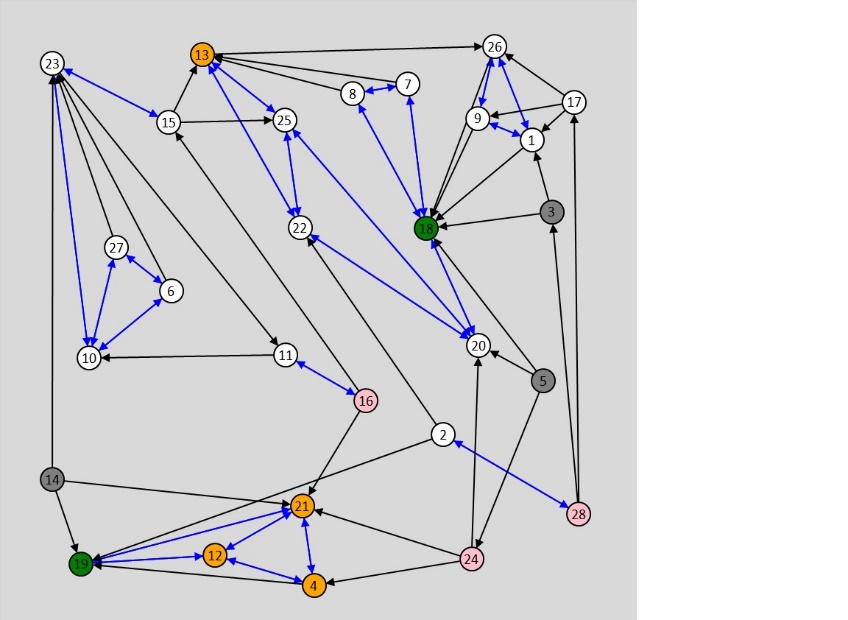

Fig. 1 Sociogram 5.a

The directions of the arrows from person A to person B indicate that person A likes person B. The student statuses are as follows:

- Popular (green): [18, 19]

- Rejected (grey): [3, 5, 14]

- Controversial (orange): [4, 12, 13, 21]

- Ignored (pink): [16, 24, 28]

- Average (white): [1, 2, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 15, 17, 20, 22, 23, 25, 26, 27]

Popular include 7% of students, rejected 11%, controversial 14%, ignored 11% and average 57%. Most of the students of the 5.a belong to the group of students with an average sociometric position.

From the sociogram, we see that students from vulnerable groups are in the controversial, rejected and average group. Most students from vulnerable groups are in the group of students with an average sociometric position. At the same time, they represent half of the controversial group.

Students with an average sociometric position are neither popular nor unpopular, they are behaviourally unremarkable, they are usually the standard of comparison - students from more extreme groups are compared to them. Students from the controversial group are often aggressive and strong, they have a great influence on the group, as they have leadership skills (Williams and Gilmour, 1994), which is consistent with the results in 5.a, as individuals from the controversial group often convince other classmates that join them in inappropriate behaviour (teasing, teasing classmates, hiding property, etc.).

B. Sociometry of the 5.b class

There are 27 students in 5.b, 13 girls (48%) and 14 boys (52%). In the class there are 3 (11%) pupils with behavioural problems (7, 14 and 23), 2 (7%) pupils with additional professional help (3 and 16) and 2 (7%) pupils with learning difficulties (22 and 24). In total, in 5.b, 7 students (25%) belong to vulnerable groups of students.

TABLE II

Sociometric statuses of students from vulnerable groups in 5.b

|

Student ID |

SS |

|

3 |

1 |

|

7 |

0,9 |

|

14 |

0,88 |

|

16 |

0,96 |

|

22 |

0,88 |

|

23 |

0,88 |

|

24 |

0,88 |

Students with additional professional help have a medium sociometric status. The remaining students from vulnerable groups have a low sociometric status (Table 2).

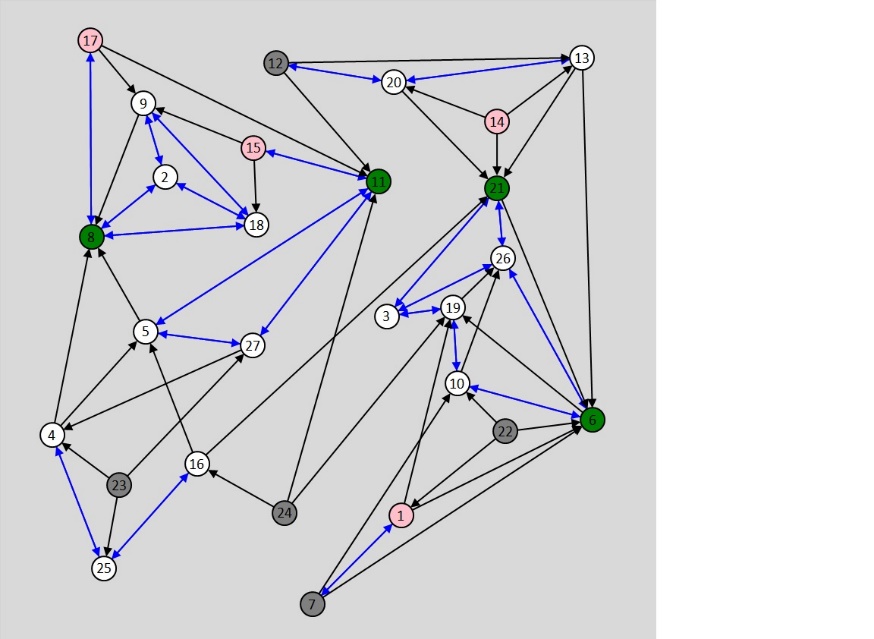

Fig. 2 Sociogram 5.b

The directions of the arrows from person A to person B indicate that person A likes person B. The student statuses are as follows:

- Popular (green): [6, 8, 11, 21]

- Rejected (grey): [7, 12, 22, 23, 24]

- Controversial (orange): []

- Ignored (pink): [1, 14, 15, 17]

- Average (white): [2, 3, 4, 5, 9, 10, 13, 16, 18, 19, 20, 25, 26, 27]

Popular include 15% of students, rejected 19%, controversial 0%, ignored 15% and average 51%. Most of the students of the 5.b belong to the students with an average sociometric position. From the sociogram, we see that students from vulnerable groups belong to the group of rejected, ignored and the group of students with an average sociometric position. Most of them took the position of rejected. Ignored students are often loners, are less aggressive in social interaction with other students, do not differ in behaviour from popular or at-risk groups of students, but are not a risk group for later adjustment problems (Williams and Gilmour, 1994). Rejected students are a risk group for later adjustment problems, as they are often aggressive, have a low level of prosocial behaviour, a high level of disruptive behaviour, a high level of social anxiety or withdrawal, and a high level of indifferent or immature behaviour (Bierman, 2004). The description of individuals in the group of ignored and rejected students is also consistent with the behaviour of students from the mentioned groups in 5b. Individuals from the rejected group stand out, as they are less popular among their classmates, are rarely chosen by their classmates for group work, and often destroy school property or the property of their classmates. Just as often, they disrupt the lesson with their immature comments or interrupting the teacher's explanation by jumping into the conversation.

C. Sociometry of the 5.c class

There are 27 students in 5.c, 15 girls (55%) and 12 boys (45%). In the class there are 2 (7%) pupils with behavioural problems (8 and 19), 3 (11%) pupils with additional professional help (2, 6 and 27) and 4 (15%) pupils with learning difficulties (1, 10, 17 and 21). In total, therefore, in section 5b, 9 students (33%) belong to vulnerable groups of students.

TABLE III

Sociometric statuses of students from vulnerable groups in 5.c

|

Student ID |

SS |

|

1 |

0,9 |

|

2 |

1 |

|

6 |

1 |

|

8 |

1 |

|

10 |

1 |

|

17 |

1 |

|

19 |

1,08 |

|

21 |

1 |

|

27 |

0,88 |

From Table 3, we see that two students have a low sociometric status. The remaining students from vulnerable groups have a medium sociometric status.

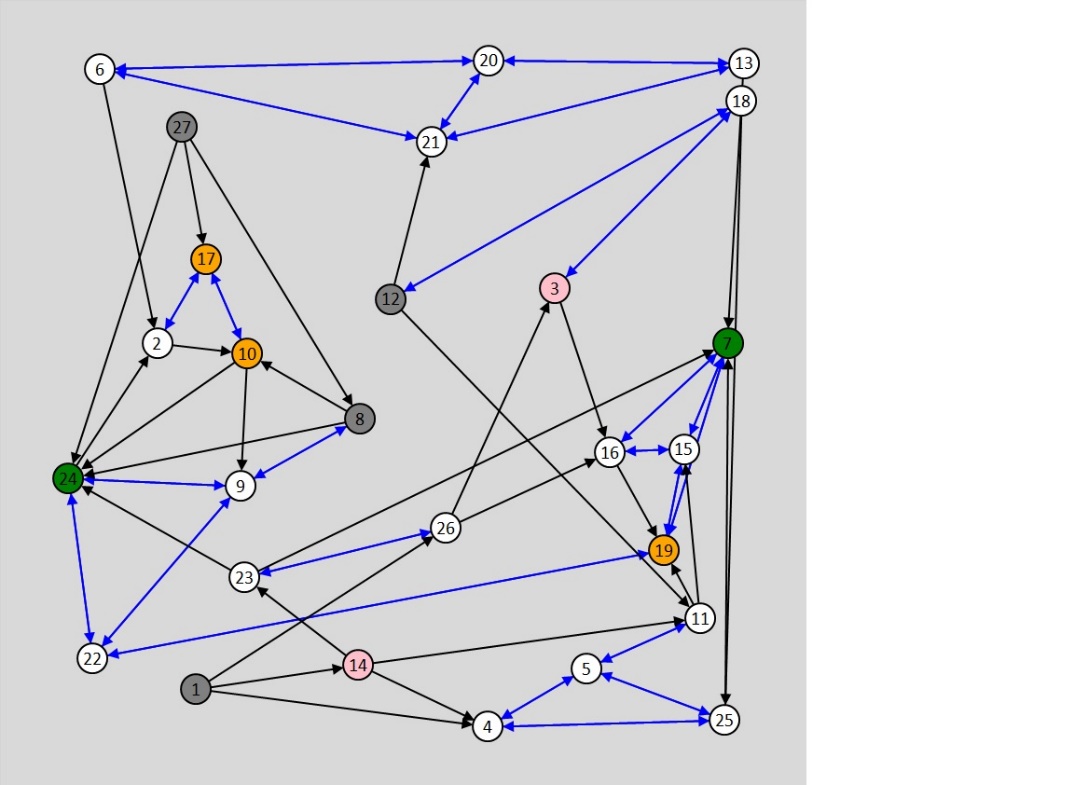

Fig. 3 Sociogram 5.c

Fig. 3 Sociogram 5.c

The directions of the arrows from person A to person B indicate that person A likes person B. The student statuses are as follows:

- Popular (green): [7, 24]

- Rejected (grey): [1, 8, 12, 27]

- Controversial (orange): [10, 17, 19]

- Ignore (pink): [3, 14]

- Average (white): [2, 4, 5, 6, 9, 11, 13, 15, 16, 18, 20, 21, 22, 23, 25, 26]

7% of students fall into the popular group, rejected 15%, controversial 11%, ignored 7% and average 60%. Most of the students of the 5.c belong to the students with an average sociometric position.

From the sociogram, we see that students from vulnerable groups belong to the group of rejected, controversial and average. Most of them took the position of controversial and the average sociometric position. In the case of the controversial and rejected, they occupy whole groups.

Students from the controversial group are often aggressive, and at the same time, with their leadership skills, they influence the rest of their classmates to follow them in pulling pranks or other forms of inappropriate behaviour (chatting during class, mocking, walking around the classroom without the teacher's permission, leaving class, etc.), which is consistent with the theoretical description of the mentioned group (Williams and Gilmour, 1994). Rejected students of the 5.c are unpopular among classmates, a demanding group for teachers, difficult to control, loud and present in most incidents that occur in this class (injuries, accidents), which supports the theoretical description of the group (Bierman, 2004).

Williams and Gilmour (1994) attribute prosocial behaviour, respectful behaviour to authority and rules, and active involvement in positive interactions with peers to popular students, which is consistent with the behaviour of popular students in all three sections - they are often involved in teamwork, school projects, selected for class representatives, they help teachers.

Most students in 5.a, 5.b and 5.c belong to the group of students with an average sociometric position, so we can confirm hypothesis 1 (H1: Most students in each class belong to the group of students with an average sociometric position). At the same time, the mentioned group of students in this generation of fifth graders is unremarkable for most teachers, teachers often take them as examples for comparison with other students. Students are manageable, obedient during class, they do not stand out in terms of academic achievements, nor in terms of behaviour, which is also consistent with theory (Williams and Gilmour, 1994). They are often observers of the disturbing behaviour of their classmates, so they often help teachers in researching and determining what happened in individual situations in the class.

The majority of students from vulnerable groups in 5.a belong to the group of students with an average sociometric position, in 5.b to the group of rejected students and in 5.c to the group of controversial and to the group of students with an average sociometric position, therefore hypothesis 2 (H2: Most students from vulnerable groups is located in the group of rejected or ignored students in each class) we cannot confirm.

Students from vulnerable groups have a low or medium sociometric status in all three classes, so hypothesis 3 (H3: Students from vulnerable groups have a low or medium sociometric status in each class) can be confirmed.

Conclusion

Through research, we found that the majority of fifth graders belong to the group of students with an average sociometric position. We also found that most students from vulnerable groups have a medium or low sociometric status. Social acceptance among students has a crucial influence on their school performance. When students feel accepted and included in the school environment, they show greater motivation to learn and achieve better results. This is extremely important, as it underlines the need to create an inclusive school environment where every student feels welcome and supported. Research by Jones and Ostfeld (2018) showed that students who have a high level of social acceptance are more focused on learning and achieve better academic results. Social acceptance has also been found to have a strong impact on students\' psychological well-being (Smith et al., 2019). However, we failed to confirm the assumption that students from vulnerable groups belong to the rejected or ignored groups, as they occupied different sociometric groups. This can be explained by the observation of Košir (2017b) that the sociometric position of an individual does not only depend on his characteristics, but also on the norms and relations within the individual group in which he is located. In addition, other factors that influence social acceptance, such as cultural differences and social status, must also be considered. It is also necessary to mention an important limitation of the research - a small sample, because of which the results and findings cannot be generalized to all school communities.

References

[1] Baydik, B. & Bakkaloglu, H. (2009). Predictors of sociometric status for low socioeconomic status elementary mainstreamed students with and without special needs. Educational Science: Theory and Practice, 9, 435–447. [2] Bierman, K. (2004). Peer rejection: Developmental processes and intervention strategies. New York: Th e Guilford Press. [3] Coie, J. D., Dodge, K. A. & Coppotelli, H. A. (1982). Dimensions and types of social status: A crossage perspective. Developmental Psychology, 18, 557–570. [4] Drexel University (n. d.). How to Promote Inclusion in the Classroom. Drexel University School of Education. https://drexel.edu/soe/resources/student-teaching/advice/Promote-Inclusion-in-the-Classroom/ [5] Dudley-Marling, C. C. & Edmiaston, R. (1985). Social status of learning disabled children and adolescents: A review. Learning Disability Quarterly, 8, 189–204. [6] Garrote, A., Felder, F., Krahenmann, H., Schnepel, S., Sermier Dessemontet, R. & Moser Opitz, E. (2020). Social Aceptance in Inclusive Clasrooms: The Role of TeacherAttitudes Toward Inclusion and Clasroom Management. Frontiers: Educational Psychology. https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/feduc.2020.582873/full [7] Gifford-Smith, M. E. & Brownell, C. A. (2003). Childhood peer relationships: Social acceptance, friendship, and peer networks. Journal of School Psychology, 41, 235–284. [8] Horvat, M. & Košir, K. (2013). Socialna sprejetost nadarjenih u?encev in u?encev z dodatno strokovno pomo?jo v osnovni šoli. Psihološka obzorja, 22, 156–166. https://doi.org/10.20419/2013.22.387. [9] Jackson, L. D. & Bracken, B. A. (1998). Relationship between students’ social status and global and domain-specific self-concepts. Journal of School Psychology, 36, 233–246. [10] Jones, A. & Ostfeld, M. (2018). The Relationship Between Social Acceptance and Academic Achievement: A Meta-Analysis. Journal of Educational Psychology, 110(5), 632–648. doi:10.1037/edu0000244 [11] Košir, K. (2017a). Pedagoška psihologija za u?itelje: izbrane teme. Maribor: Univerzitetna založba [12] Košir, K. (2017b). Sociometri?ni status v šoli: koncept in merjenje. In: I. Devetak, B. Šimek, K. Košir (ed.). Socializacija, vzgoja in izobraževanje (p. 71–90). Ljubljana: Pedagoški inštitut. [13] Košir, K. & Pe?jak, S. (2007). Dejavniki, ki se povezujejo s socialno sprejetostjo v razli?nih obdobjih šolanja. Psihološka obzorja, 16(3), 49-73. http://psiholoska-obzorja.si/arhiv_clanki/2007_3/kosir.pdf [14] Kuhne, M. & Wiener, J. (2000). Stability of social status of children with and without learning disabilities. Learning Disabilities Quarterly, 23, 64–75. [15] Marenti? Požarnik, B. (2023). Psihologija u?enja in pouka: od pou?evanja k u?enju. 2. prenovljena izdaja, 5. natis, Ljubljana: DZS. [16] Mikli?, L. (2013). Kako se u?enci priseljenci vklju?ujejo v šolsko okolje [Raziskovalna naloga, OŠ Franca Rozmana-Staneta Maribor] https://zpm-mb.si/wp-content/uploads/2016/01/O%C5%A0_Sociologija_Kako_se_u%C4%8Denci_priseljenci.pdf [17] Peterka, A. (2016). Socialna sprejetost otrok priseljencev v osnovni šoli [Master thesis, Univerza v Ljubljani, Pedagoška fakulteta] http://pefprints.pef.uni-lj.si/3451/1/Ana_Peterka_Socialna_sprejetost_otrok_priseljencev_v_osnovni_%C5%A1oli_2016.pdf [18] Schmidt, M. (2001). Socialna integracija otrok s posebnimi potrebami v osnovno šolo. Maribor, Slovenija: Pedagoška fakulteta Maribor. [19] Smith, J. K., Brown, S. L. & Doe, R. (2019). Social Acceptance and Psychological Well-Being in Adolescents: A Longitudinal Study. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 48(3), 576–589. doi:10.1007/s10964-018-0955-4. [20] Stone, W. L. & La Greca, A. M. (1990). The social status of children with learning disabilities: A reexamination. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 23, 32–37. [21] Špes, T. & Košir, K. (2017). Socialna sprejetost srednješolcev v razredu in na socialnem omrežju Facebook. Psihološka obzorja, 26, 33-40. http://psiholoska-obzorja.si/arhiv_clanki/2017/spes_kosir.pdf [22] Wiener, J., Harris, P. J. & Shirer, C. (1990). Achievement and social-behavioral correlates of peer status in LD children. Learning Disability Quarterly, 13, 114–127. [23] Wiener, J. & Schneider, B. H. (2002). A multisource exploration of the friendship patterns of children with and without learning disabilities. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 30, 127–141. [24] Wiener, J. & Tardif, C. Y. (2004). Social and emotional functioning of children with learning disabilities: Does special education placement make a difference? Learning Disabilities Research & Practice, 19, 20–32. [25] Williams, B.T.R. & Gilmour, J.D. (1994). Annotation: Sociometry and peer relationships. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 35(6), 997-1013.

Copyright

Copyright © 2024 Danijela Jelisavac. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Download Paper

Paper Id : IJRASET64687

Publish Date : 2024-10-19

ISSN : 2321-9653

Publisher Name : IJRASET

DOI Link : Click Here

Submit Paper Online

Submit Paper Online