Ijraset Journal For Research in Applied Science and Engineering Technology

- Home / Ijraset

- On This Page

- Abstract

- Introduction

- Conclusion

- References

- Copyright

Menstrual Symptoms: The Importance of Social Factors in Women\'s Experiences

Authors: Dr. Chilakalapudi Meher Babu

DOI Link: https://doi.org/10.22214/ijraset.2024.64046

Certificate: View Certificate

Abstract

This study aimed to investigate menstrual symptoms and their impact on everyday life and well-being among postmenarchal adolescents. Menstrual disorders are a common presentation in primary care. Heavy menstrual bleeding is the most common concern, and is often treated by medical and surgical means despite lack of pathology. Menstruation is a natural phenomenon for women during their reproductive years. Our aim was to describe women’s experiences of menstruation across the lifespan. Qualitative interviews, with a narrative approach, were conducted with 12 women between 18 and 48 years of age in Sweden. Using thematic analysis, we found menstruation to be a complex phenomenon that binds women together. It is perceived as an intimate and private matter, which makes women want to conceal the occurrence of menstrual bleeding. Over time, menstruation becomes a natural part of women’s lives and gender identity. Health professionals play a central role supporting women to deal with menstruation.

Introduction

I. INTRODUCTION

Menstruation is a natural phenomenon for women during their reproductive years. Our aim was to describe women’s experiences of menstruation across the lifespan. Qualitative interviews, with a narrative approach, were conducted with 12 women between 18 and 48 years of age in Sweden. Using thematic analysis, we found menstruation to be a complex phenomenon that binds women together. It is perceived as an intimate and private matter, which makes women want to conceal the occurrence of menstrual bleeding. Over time, menstruation becomes a natural part of women’s lives and gender identity. Health professionals play a central role supporting women to deal with menstruation.

A. What are the Chemicals in the Menstrual cycle?

The menstrual cycle is regulated by the complex interaction of hormones: luteinizing hormone, follicle-stimulating hormone, and the female sex hormones estrogen and progesterone. The menstrual cycle has three phases: Follicular (before release of the egg) Ovulatory (egg release)

B. What are the Ingredients of a Sanitary Pad?

Pads and pantyliners are made of principal materials such as wood pulp, nonwoven fabrics made from polymers (PE, PP), SAP, and adhesives of natural and synthetic resins. These raw materials are chosen for their ability to absorb and retain fluids, to avoid leakage, and to provide comfort (Yokura & Niwa, 2000). The majority of these secretions are mostly made up of water and electrolytes such as sodium or potassium. This ionic solution helps keep the pH low and prevents foreign bacteria from flourishing Product shall consist of a top sheet, middle absorbent core consisting of cotton, polyester and other absorbent fabrics and a leak proof layer consisting of typically, polyurethane laminate (PUL) at the bottom. n a series of lab analyses commissioned between 2020 and 2022 by the consumer watchdog site Mamavation and Environmental Health News, 48% of sanitary pads, incontinence pads, and panty liners tested were found to contain PFAS, as were 22% of tampons and 65% of period underwear.

II. ROLE IN MENSTRUATION

Menarche is the first time a person gets their menstrual period, and it typically occurs between the ages of 12 and 13 years. However, menarche can occur at any time between 8 and 15 yearsTrusted Source of age.

Menstrual disorders are a common presentation in primary care. Menorrhagia, or heavy menstrual bleeding, has been the most common cited reason for hysterectomy, despite frequent lack of pathology. Women's reports of heavy bleeding do not correlate well with blood loss, which has led to questions about what women are actually concerned about. Lilford remarked on women's willingness to undergo extensive medical and surgical treatment despite lack of pathology, and suggested that more research was required on the psychosocial factors that influence women.Stirrat suggested that greater attention to ‘puzzling’ psychosocial influences is required to understand women's health-related behaviour.

In psychosocial studies the emphasis has been on characteristics of women as individuals, for example, studies exploring attitudes to menstruation or psychological morbidity. The status of menstruation in society as a whole has not been seen as important when considering women's concerns about menstruation or their menstruation-related behaviours.

III. PERCEIVED SOCIAL RULES RELATED TO MENSTRUATION

- A woman must keep private that she is having a period by wearing suitable clothes and by changing usual activities to prevent any visible evidence of sanitary protection.

- She should avoid any episode of staining or leakage by changing activities, and/or by wearing adequate protection in advance of her period.

- A woman will not explain absence from work or difficulties in carrying out duties by explaining that she is menstruating.

- If a woman feels she must give some explanation, she should say she has stomach cramps or that she is unwell.

- A woman will talk to other women about periods only if she knows the other person well, and if the other woman is judged likely to be understanding or to have helpful information and they are in private.

- A woman may speak to another woman who she does not know well if the alternative is breaking the rule that a period must be kept private.

- In relation to rules 5 and 6 above, non-specific terms or euphemisms such as ‘time of the month’ are adequate.

- It is particularly important not to talk to men about periods; it is considered appropriate to inform sexual partners about menstruation, but sexual intercourse at this time may be considered distasteful.

- Men and women may be aware that you are having a period, but they will abide by the rules and not mention it.

A. How to Promote Menstrual Hygiene?

- Promong menstrual hygiene is achieved through:

- Provision of health education to girls and women on menstruaon and menstrual hygiene

- Increasing community acon to improve access to clean toilets with water, both at home and in schools

- Promoting the availability and use of sanitary products Enabling safe disposal of sanitary products

B. What are the Problems that a Girl may Encounter During Menstruaon?

The difficules that girls may experience during menstruaon are:

- Irregular periods

- Heavy periods

- Painful periods

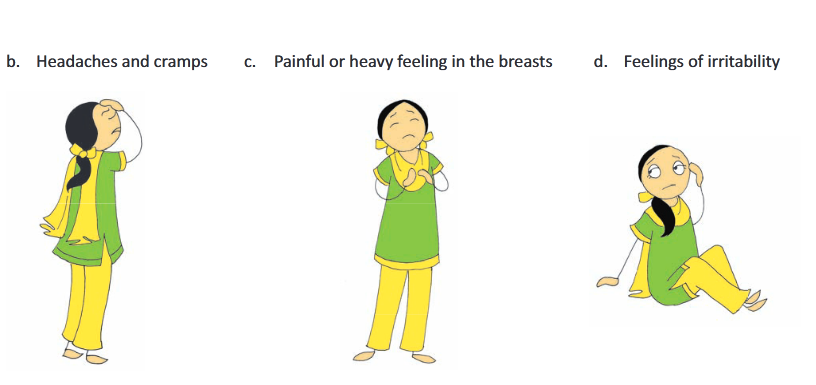

Irregular Periods: For the first few years of menstruation, cycles are oen irregular. They may be shorter (3 weeks) or longer (6 weeks). A young girl may even have only three or four periods a year. A girl’s cycles will usually become regular within two to three years aer menarche. Heavy periods: A heavy period is one which lasts longer than eight days, saturates the napkin within an hour or includes large clots of blood in the menstrual flow. This is common in adolescents because of slight imbalance in chemical hormones secreted by the body. However, if this happens regularly, it leaves the girl feeling exhausted; which means that the body is losing more blood than it is producing. The girl should then consult a doctor immediately. Painful period: Slight pain during periods is quite normal. This is due to the secreations of a chemical called prostaglandins in larger quanty than normal. This leads to nausea, headaches, diarrhoea and severe cramps. Usually, this lasts only for a day or two. To get relief from these symptoms, a girl should try the following methods:

IV. FOLLICULAR PHASE

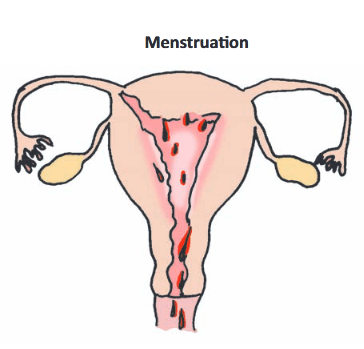

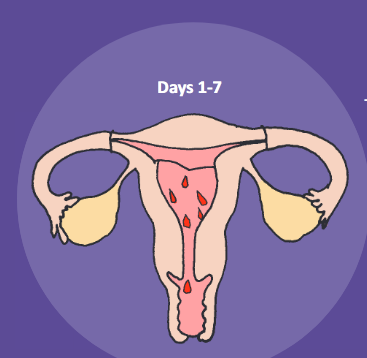

The first day of a period marks the beginning of a new menstrual cycle. During a period, blood and tissue from the uterus exit the body through the vagina. Estrogen and progesterone levels are very low at this point, and this can cause irritability and mood changes.

The pituitary gland also releases FSH and LH, which increase estrogen levels and signal follicle growth in the ovaries. Each follicle contains one egg. After a few days, one dominant follicle will emerge in each ovary. The ovaries will absorb the remaining follicles.

As the dominant follicle continues growing, it will produce more estrogen. This increase in estrogen stimulates the release of endorphins that raise energy levels and improve mood.

Estrogen also enriches the endometrium, which is the lining of the uterus, in preparation for a potential pregnancy.

V. OVULATORY PHASE

During the ovulatory phase, estrogen and LH levels in the body peak, causing a follicle to burst and release its egg from the ovary.

An egg can survive for around 12–24 hoursTrusted Source after leaving the ovary. Fertilization of the egg can only occur during this time frame.

VI. LUTEAL PHASE

During the luteal phase, the egg travels from the ovary to the uterus via the fallopian tube. The ruptured follicle releases progesterone, which thickens the uterine lining, preparing it to receive a fertilized egg. Once the egg reaches the end of the fallopian tube, it attaches to the uterine wall.

An unfertilized egg will cause estrogen and progesterone levels to decline. This marks the beginning of the premenstrual week.

Finally, the unfertilized egg and the uterine lining will leave the body, marking the end of the current menstrual cycle and the beginning of the next.

VII. ROLE IN PREGNANCY

Pregnancy starts the moment a fertilized egg implants in the wall of a person’s uterus. Following implantation, the placenta begins to develop and starts producing a number of hormones, including progesterone, relaxin, and human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG).

Progesterone levels steadily rise during the first few weeks of pregnancy, causing the cervix to thicken and form the mucus plug.

The production of relaxin prevents contractions in the uterus until the end of pregnancy, at which point it then helps relax the ligaments and tendons in the pelvis.

Rising hCG levels in the body then stimulate further production of estrogen and progesterone. This rapid increase in hormones leads to early pregnancy symptoms, such as nausea, vomiting, and the need to urinate more often.

Estrogen and progesterone levels continue to rise during the second trimester of pregnancy. At this time, cells in the placenta will start producing a hormone called human placental lactogen (HPL). HPL regulates women’s metabolism and helps nourish the growing fetus.

Hormone levels decline when a pregnancy ends and gradually return to prepregnancy levels. When a person breastfeeds, it can lower estrogen levels in the body, which may prevent ovulation occurring.

VIII. ROLE IN MENOPAUSE

Menopause occurs when a person stops having menstrual periods and is no longer able to become pregnant. In the United States, the average age at which a woman experiences menopause is 52 yearsTrusted Source.

A. Role in Menopause

Menopause occurs when a person stops having menstrual periods and is no longer able to become pregnant. In the United States, the average age at which a woman experiences menopause is 52 yearsTrusted Source.

Perimenopause refers to the transitional period leading up a person’s final period. During this transition, large fluctuations in hormone levels can cause a person to experience a range of symptoms.

Symptoms of perimenopause can include:

- irregular periods

- hot flashes

- sleeping difficulties

- mood changes

- vaginal dryness

According to the Office on Women’s HealthTrusted Source, perimenopause usually lasts for about 4 years but can last anywhere between 2 and 8 years.

A person reaches menopause when they have gone a full year without having a period. After menopause, the ovaries will only produce very small but constant amounts of estrogen and progesterone.

Lower levels of estrogen may reduce a person’s sex drive and cause bone density loss, which can lead to osteoporosis. These hormonal changes may also increase the risk of heart disease and stroke.

IX. ROLE IN SEXUAL DESIRE AND AROUSAL

Estrogen, progesterone, and testosterone all affect sexual desire and arousal. Having higher levels of estrogen in the body promotes vaginal lubrication and increases sexual desire. Increases in progesterone can reduce sexual desire.

There is some debate around how testosterone levels affect female sex drive.

Low levels of testosterone may lead to reduced sexual desire in some women. However, testosterone therapy appears ineffective at treating low sex drive in females.

According to a systematic review from 2016Trusted Source, testosterone therapy can enhance the effects of estrogen, but only if a doctor administers the testosterone at higher-than-normal levels. This can lead to unwanted side effects.

These side effects can include:

- weight gain

- irritability

- balding

- excess facial hair

- clitoral enlargement

X. HORMONAL IMBALANCE

Hormonal balance is important for general health. Although hormonal levels fluctuate regularly, long-term imbalances can lead to number of symptoms and conditions.

The Always menstrual pads were found to contain several chemicals of concern, including the following: Styrene: carcinogen. Chloromethane: reproductive toxicant. Chloroethane: carcinogen.

Signs and symptoms of hormone imbalances can include:

- irregular periods

- excess body and facial hair

- acne

- vaginal dryness

- low sex drive

- breast tenderness

- gastrointestinal problems

- hot flashes

- night sweats

- weight gain

- fatigue

- irritability and irregular mood changes

- anxiety

- depression

- difficulty sleeping

Hormonal imbalances can be a sign of an underlying health condition. They can also be a side effect of certain medications. For this reason, people who experience severe or recurring symptoms of hormonal imbalances should speak to a doctor.

In females, potential causes of hormonal imbalances include:

- polycystic ovary syndrome

- primary ovarian insufficiency

- hormonal birth control

- hormone replacement therapy

- excess body weight

- ovarian cancer

- stress

Conclusion

Key Activities to Promote Menstrual Hygiene 1) Organising monthly meengs on a fixed day for adolescent girls: One of your responsibilies is to organise monthly meengs on a fixed day at the Anganwadi Centre or Panchayat Bhavan for adolescent girls in the target age group of 10-19 years. The day will be fixed by the state government and will be observed throughout the state. The purpose of this meeting is to provide health education to girls on issues of menstruation and menstrual hygiene. You should use the flip book provided to you to conduct this session. The second purpose of this meeting is to make sanitary napkins available to the girls. This can be done through the support of the Anganwadi worker and other members of the women self help groups in the village. The meeting should be held in collaboration with the Kishori Samooh or an Adolescent Resource Centre under the SABLA scheme, where it exists. For this, you will be paid an incentive of Rs. 50. These meeting will also serve as venues where information on adolescent-related health can be communicated. 2) Conducting home visits for girls who do not regularly attend monthly meetings: Monthly meetings should be complemented by household visits to promote menstrual hygiene among girls and other influencers in the family, who are unable to attend the monthly meetings. This would motivate attendance for future meetings.

References

REFERENCES [1] Allen, K. R., & Goldberg, A. E. (2009). Sexual Activity During Menstruation: A qualitative study. Journal of Sex Research, 46, 535-545. [2] Amaral, M. C. E., Hardy, E., & Hebling, E. M. (2011). Menarche among Brazilian women: memories of experiences. Midwifery, 27, 203-208. [3] Andrist, L. C., Hoyt, A., Weinstein, D., & McGibbon, C. (2004). The Need to Bleed: Women’s Attitudes and Beliefs about Menstrual Suppression. Journal of American Academy of Nurse Practitioners, 16, 31-37. [4] Ballard, K. D., Kuh, D. J., & Wadsworth, M. E. J. (2001). The role of the menopause in women’s experiences of the ‘change of life’. Sociology of Health & Illness, 23, 397-424. [5] Barnard, K., Frayne, S. M., Skinner, K. M., & Sullivan, L. M. (2003). Health Status among Women with Menstrual Symptoms. Journal of Women’s Health, 12, 911-919. [6] Beausang, C. C., & Razor, A. G. (2000). Young western women’s experiences of menarche and menstruation. Health Care for Women International, 21, 517-528. [7] Berterö, C. (2003). What do women think about menopause? A qualitative study of women’s expectations, apprehensions and knowledge about the climacteric period. International Nursing Review, 50, 109-118. [8] Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3, 77-101. [9] Burrows, B., & Johnson, S. (2005). Girls’ experiences of menarche and menstruation. Journal of Reproductive and Infant Psychology, 23, 235-249. [10] Çevirme, A. S., Çevirme, H., Karaoglu, L., Ugurlu, N., & Korkamaz, Y. (2010). The perception of menarche and menstruation among Turkish married women: attitudes, experiences, and behaviors. Social Behavior and Personality, 38, 381-394. [11] Fahs, B. (2011). Sex during menstruation: Race, sexual identity, and women’s accounts of pleasure and disgust. Feminism & Psychology, 21, 155-178. [12] Fingerson, L. (2005). Agency and the body in adolescent menstrual talk. Childhood, 12, 91-110. [13] George, S. A. (2001). The Menopause Experience: A Woman’s Perspective. Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic, & Neonatal Nursing, 31, 77-85.

Copyright

Copyright © 2024 Dr. Chilakalapudi Meher Babu. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Download Paper

Paper Id : IJRASET64046

Publish Date : 2024-08-22

ISSN : 2321-9653

Publisher Name : IJRASET

DOI Link : Click Here

Submit Paper Online

Submit Paper Online